Posted by Doug Turetsky, January 7, 2013

Photo Credit: Flickr/-LucaM- Photograph

Last month, the U.S. Conference of Mayors released a report that offered a discouraging view of homelessness across the country. Among 25 cities participating in a survey by the organization, 15 said the number of homeless in their communities had been increasing and another three said the number had stayed the same as last year. The other seven reported declines.

Some of the biggest cities in the survey admitted turning away a significant share of their homeless population because emergency shelters simply don’t have enough beds. Philadelphia reported turning away a third of those seeking shelter, Charlotte 25 percent, and Boston 20 percent.

New York City didn’t participate in the survey, but it could have provided some stark numbers of its own. Not only is the number of homeless on the rise here, but individuals and families are experiencing ever-longer stays in shelter beds. While court orders dating to the 1980s provide the homeless with a legal right to shelter, some advocates would argue that the city effectively turns people away through its eligibility review process. Still, with a growing number of people entering the homeless system, the city has added new shelter sites in recent months.

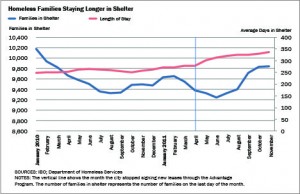

Over the first five months of this fiscal year (July-November), an average of 11,184 families, including those with children and adult families without children, spent the night in the city’s shelter system. That’s up by more than 1,600 families, or 17 percent, compared with the same five-month period last year.

These families are remaining in the shelter system more than a month longer on average than last year. Families with children typically spent 355 days in the city’s shelters as of the first four months of fiscal year 2013—up 40 days compared with the first four months of last fiscal year. For families without children, the picture is much the same. Average stays in the shelter system increased by 51 days, to 443 days during the first four months of this fiscal year.

The number of single adults spending the night in a city shelter has also grown by 10 percent, and averaged 9,213 over the first five months of this fiscal year. They, too, are also spending more days on average in the shelter system: 275 days during the first four months of this year, 12 days more than for the same four months last year.

There’s been a steady rise in the number of homeless and longer stays in the shelter system since the city eliminated the Advantage rental assistance program last year . The program had helped the homeless, mostly homeless families, leave city shelters by providing temporary rent subsidies. The program ended after the state eliminated its share of funding for the program, which cost in total about $210 million in 2011. The city’s share of the program’s cost was about $114 million.

Not surprisingly, more people and longer stays are driving up shelter spending. In November, the Mayor added $42.9 million in city, state, and federal funds to the budget for family shelters, bringing the total budget for 2013 to $466.5 million.

But IBO’s Elizabeth Brown says the additional funding is not enough to meet likely costs. Based on recent trends, she estimates that providing families with emergency shelter will cost about $42 million more than the Bloomberg Administration has budgeted for this year. Costs for emergency shelter for homeless single adults have also climbed.

In June 2004, the Mayor announced a five-year plan to cut homelessness by two-thirds. That plan never came close to meeting its goal and in recent months the city has sheltered record numbers of homeless New Yorkers. On Christmas Eve, more than 47,300 children and adults bedded down in the city’s shelters—a population about equal in size to the number of people who live in the upstate city of Binghamton.