Posted by Doug Turetsky. February 5, 2014

A little noticed report, prepared by the Department of Citywide Administrative Services and the Mayor’s Office of Operations and released on the Bloomberg Administration’s last day in office, looks at changes in the compensation and composition of the municipal workforce over the past decade. The report, which is not available on the city’s website but IBO provides here could fuel arguments on both sides of the negotiations to settle the city’s expired labor contracts.

According to the report, the median base salary, which doesn’t include overtime, pension, or fringe benefit costs, for full-time city employees in fiscal year 2012 was $65,299. That’s relatively little-changed from an inflation-adjusted median salary of $64,698 in 2003, Mayor Bloomberg’s first full fiscal year in office. As the report states, “Median [inflation-adjusted] salaries have remained stable over the past ten years, ranging from a low of $59,000 in 2005 to a high of $66,000 in Fiscal 2010.”

While union leaders may look at those numbers and see fodder for arguing that salaries for municipal workers barely stayed ahead of inflation over that 10-year period, that small gain might look pretty good to a large share of the rest of the city. For city residents as a whole, median earnings adjusted for inflation have not yet rebounded to their 2005 level. Median citywide earnings in 2005 were $37,091 and just $34,019 in 2012, according to Census Bureau figures compiled by IBO’s Julie Anna Golebiewski.

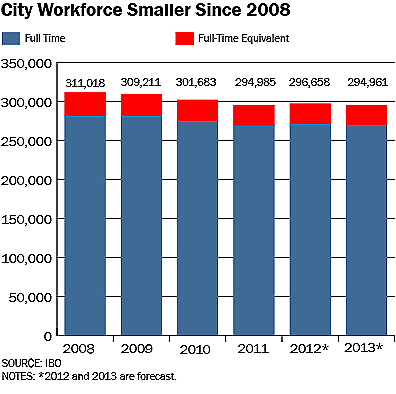

The report, New York City Government Workforce Profile Report, covers 39 agencies with nearly 327,800 full-time and full-time equivalent employees. The report includes all the city agencies that report to the Mayor along with the Health and Hospitals Corporation and New York City Housing Authority, even though these two are technically not city agencies. So that means agencies such as IBO and the Campaign Finance Board and employees of other elected officials are not included.

Overall, nearly one-third of the city’s full-time workforce—about 100,000 employees— had base salaries of $50,000 or less in 2012. On the other end of the salary scale, 9 percent of the municipal workforce—about 27,000 staffers—had base salaries of $100,000 or more.

On the agency level, median base salaries also varied. The very highest was the School Construction Authority, where the median base salary for its staff of 660 was $100,400. The uniformed services tended to have substantially higher median salaries than workers in other agencies. At $76,488, the median salaries for the police, fire, and correction departments outstripped the 2012 citywide median. The sanitation department, with a median salary of $69,339 was nearer the median for all city employees.

Conversely, a number of agencies had median base salaries well below the citywide level. The Taxi and Limousine Commission’s 460 full- and full-time equivalent employees had a median salary of $39,205 in 2012. They were followed closely by the housing authority’s 11,500 staff members with a median salary of $40,624.

In addition to information on salaries, the report provides numerous demographic details on the city’s workforce—from gender and racial and ethnic profiles of agencies and various occupational categories to information on employees’ average years of city service, civil service status, and eligibility for retirement. The report’s intent is clearly stated up front: “The goal of this report is to make New York City’s municipal workforce…transparent to the people it serves, and to provide interested parties with the personnel data needed for analysis and planning.”

Somehow that goal of transparency faded away in the waning hours of the Bloomberg Administration and this report—covering the city’s single largest expense, about $37 billion annually on its workforce—went largely unseen.