Featured Resources

Fiscal Brief

July 2020

Trouble Ahead, Trouble Behind:

The Impact of Declining Dedicated Tax Revenue on MTA Finances

PDF version available here.

Summary

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority and its affiliate, NYC Transit, which runs the city’s subways and most of the buses, are highly dependent on two sources of revenue: fares from riders and dedicated taxes. The spread of Covid-19 led to a virtual shutdown of the city for months, causing a collapse in transit ridership and fare revenue. The pandemic-related shutdown also decimated the local economy, leading to a drop in payrolls, sales, and other economic activity that generates dedicated tax revenue for the transportation authority.

Revenue from dedicated taxes comprised 37 percent of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s operating budget in 2019. Dedicated taxes made up a similar share of NYC Transit’s budget, or nearly $3.7 billion. IBO has estimated how deep the shortfall in expected tax revenues for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority may be. Among our key findings:

Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority faced major fiscal hurdles. With ridership and dedicated taxes expected to remain depressed for some time, those hurdles have multiplied. The transportation authority has looked to Washington for additional aid but may well turn to the state and city for help as well—though Albany and City Hall face serious fiscal challenges of their own.

Facing Financial Disaster

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA)—the state public authority responsible for providing transit services within New York City and rail service linking the city to surrounding suburbs—is facing financial disaster in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. The near-disappearance of fare revenue is one obvious reason, as are the additional expenses occasioned by extra cleaning and other efforts to ensure the safety of passengers and employees.

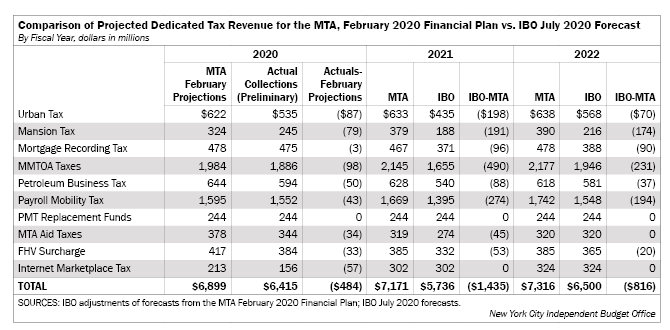

The MTA is also highly dependent on state and local tax revenue that funds various transit units within the transportation authority (referred to in MTA documents as “related entities”), revenue sources that are projected to contract sharply in the recession brought on by the pandemic. To assess the extent of the shortfall, IBO generated estimates of the MTA’s revenue from these dedicated taxes. These estimates indicate that the MTA’s dedicated tax revenues will be $484 million, $1.4 billion, and $816 million below the agency’s projections prior to the pandemic, for 2020, 2021, and 2022, respectively.

Revenue from dedicated taxes comprised 37 percent of the MTA’s operating budget revenues in 2019, nearly the same share as fare revenue. The operating budget for NYC Transit, which runs the subways and most of the public bus service within the five boroughs, is more dependent on fares than the MTA overall (almost 46 percent of the total in 2019), although the share funded by dedicated taxes was similar to the share for the MTA as a whole at around 36 percent. Over the years, IBO has published a number of reports that highlight these taxes. According to the MTA’s February 2020 Financial Plan, in 2019 NYC Transit received almost $3.7 billion from dedicated taxes. Revenue from these tax sources has dropped sharply as the Covid-19 crisis continues to depress economic activity in the city and surrounding counties.

Earlier this year IBO reported that by late March the number of weekly riders on the city’s subway system had declined 86 percent compared with the levels of late February, just before the city announced its first confirmed coronavirus case. The drop in ridership continued during April. Although May and June have seen an uptick in passengers, it seems unlikely that public transportation ridership in the New York metro area will return to anything like pre-pandemic levels anytime soon. This decline has dire implications for NYC Transit’s fare revenue, which totaled $4.6 billion in 2019.

On May 1, 2020, the MTA and McKinsey & Company released a preliminary analysis of the impact of the pandemic on the transportation authority’s 2020 finances. Also on May 1, the MTA published a supplement to its Annual Disclosure Statement, a document required of bond issuers by the federal Securities and Exchange Commission if the issuer experiences an event that materially alters information in the original disclosure statement. In the supplement, the MTA cited an estimate from the McKinsey report that due to the pandemic it would lose from $1.6 billion to $1.8 billion in tax revenue in calendar year 2020 compared with the levels projected in the MTA’s February 2020 forecast. This represents a drop of 25 percent to 28 percent. The MTA has put out preliminary tax revenue numbers through June 2020, but has not yet published revised forecasts of the individual taxes from which it receives revenue going forward. The MTA is expected to provide more details with the release of an updated financial plan this month. If—as expected—there is a shortfall in dedicated tax revenues, pressure on the city to increase its contribution to the MTA is likely to grow.

City Taxes Dedicated to the MTA

New York City taxes dedicated to the MTA include a portion of the real property transfer tax (RPTT), and the mortgage recording tax (MRT) on commercial transactions valued over $500,000. These charges are referred to collectively as the “urban tax.” There is also a city “mansion tax,” which is a surcharge on the city RPTT applied to residential properties sold for $2 million or more. The urban tax was instituted in 1982, while the city mansion tax took effect at the beginning of city fiscal year 2020. (All years hereafter refer to city fiscal years).1

Urban Tax. Ninety percent of urban tax revenue is dedicated to NYC Transit, with 6 percent allocated to the Access-A-Ride paratransit program, and 4 percent to the MTA Bus Company. In February 2020, the MTA projected urban tax revenue of $622 million in 2020, rising slightly to $633 million in 2021, and recovering to $638 million in 2022. The MTA’s preliminary total for urban tax revenue in 2020 is $535 million, 14 percent below its February forecast. IBO projects that urban tax collections will fall to $435 million in 2021, $198 million (31 percent) below the MTA’s February forecast before rebounding to $568 million in 2022. For the three-year period from 2020 through 2022, the sum of 2020 actuals and IBO’s 2021 and 2022 forecasts is $355 million (19 percent) below the forecast published by the MTA in its February 2020 Financial Plan. This steep decline in urban tax revenue reflects the fact that the market for commercial real estate—comprised chiefly of office buildings, retail space, and rental apartment buildings—is especially sensitive to changes in overall economic conditions, generally more so than residential real estate.

Mansion Tax. Another tax dedicated to the MTA is the “mansion tax,” a graduated RPTT surcharge on residential properties selling for $2 million or more in New York City, which took effect at the beginning of 2020. While this levy is formally a city tax, receipts are passed through the city budget directly to the MTA. The preliminary 2020 total for the mansion tax is $245 million. IBO projects that the tax will generate $188 million for the MTA in 2021, rising to $216 million in 2022. These forecasts are considerably below the MTA’s February 2020 forecasts, which, adjusted for city fiscal years, were $324 million in 2020, $379 million in 2021, and $390 million in 2022.2

AIBO expects mansion tax revenues to be especially sensitive to the recession because sales of luxury residences typically decline more than sales of lower-priced properties during economic downturns. Moreover, during a downturn, some properties initially priced at or slightly above $2 million will ultimately sell for less than $2 million, and not incur the tax.

State Metropolitan Commuter Transportation District Taxes Dedicated to the MTA

Most of the tax revenue dedicated to the MTA consists of portions of state taxes collected only in New York City, or in the city plus the surrounding suburbs served by Metro-North Railroad or Long Island Rail Road commuter trains. This region is referred to as the Metropolitan Commuter Transportation District. Although these are officially state taxes, most of the revenue comes from city residents. To estimate changes to MTA tax revenue, IBO relied in part on its forecasts of city taxes that are directly related to dedicated MTA taxes, or to taxes that behave similarly.

State Mortgage Recording Taxes. The MTA receives funding from two components of the mortgage recording tax. The first, known as MRT-1, is a levy of 0.3 percent on all mortgages in the commuter transportation district. The second, known as MRT-2, is a 0.25 percent charge on the value of mortgages in the district secured by residential real estate with less than seven units.

The MTA’s February 2020 forecast of MRT-1 and MRT-2, again adjusted to reflect city fiscal years, was $478 million in 2020, $467 million in 2021, and $478 million in 2022. Preliminary collections for these taxes were $475 million in 2020, almost equal to the MTA’s February forecast. However, IBO forecasts a drop to $371 million in 2021 and only a partial recovery, to $388 million, in 2022. IBO’s current MRT forecasts are $96 million (21 percent lower) for 2021, and $90 million (19 percent) lower for 2022. While the MRT is projected to decline in response to the overall economic downturn, relative strength in the refinancing of mortgages in response to both low interest rates and an increased need for liquidity is expected to cushion the fall.

Metropolitan Mass Transit Operating Assistance: Corporate Tax and Regional Sales Tax.The Metropolitan Mass Transit Operating Assistance (MMTOA) Account consists of a collection of tax revenues that are allocated to downstate transit agencies, primarily the MTA. The largest component of the MMTOA Account consists of a corporate tax surcharge in the MTA commuter district region, together with a portion of the state corporate franchise tax imposed on transportation and transmission companies. The next-largest component of the MMTOA Account is a sales tax add-on of 0.375 percent, collected on sales in the commuter transportation district. The final component of the MMTOA Account, currently about 5 percent of the total, is a portion of the petroleum business tax (PBT) that flows to the MMTOA.

The MTA ultimately receives a portion of the gross receipts from the taxes enumerated above. Adjusting for city fiscal years, the MTA projected in February that it would receive slightly under $1.9 billion from these taxes in 2020, rising to over $2.1 billion in 2021, and almost $2.2 billion in 2022. When payments already appropriated by the state but not yet received by the MTA are included, the MTA will in fact receive around $1.9 billion for 2020. IBO’s projections for subsequent city fiscal years are lower: $1.7 billion in 2021 and $1.9 billion in 2022.

Because the MTA receives only a portion of the total receipts from the taxes that make up the MMTOA, the sum of the individual tax forecasts is greater than the amount that ultimately supports transit. Nevertheless, comparing tax receipts forecast by the MTA in February with IBO’s current forecast provides additional information on the impact of the economic downturn on the net receipts. IBO has made its own projections of the corporate and sales taxes that go into the MMTOA account; we do not include the petroleum business tax component that also flows into the MMTOA account.

In its November 2019 Financial Plan, the MTA projected gross revenue for the MMTOA corporate taxes, adjusted for city fiscal years, of just under $1.3 billion in 2020, increasing to a little over $1.4 billion by 2022. The MTA’s February 2020 Financial Plan does not contain an explicit forecast of either the gross amount of these taxes, or the net amount received by the MTA. However, based on the increase in the forecast of total MMTOA revenue (both gross and net) from November 2019 to February 2020, IBO estimates that the MTA’s February forecast for the corporate taxes was around $1.4 billion in 2020, increasing to $1.5 billion in 2021 and 2022. In contrast, factoring the impact of the pandemic, which IBO expects will shrink corporate profits in the city by 15 percent in 2020 and 6 percent in 2021, we project MMTOA corporate tax revenue of $1.2 billion in 2020, $897 million in 2021, and $1.1 billion in 2022. Over the three-year period from 2020 through 2022, IBO’s current forecast for the gross receipts from these taxes is about $1.1 billion below our extrapolation from the MTA’s February forecast.

Before the Covid-19 crisis, the MTA expected to receive between $1.0 billion and $1.1 billion per year from the regional sales tax. The economic consequences of the pandemic have been particularly hard on retail outlets, restaurants, and entertainment, which IBO projects will lower taxable sales in the city by 19 percent in 2020 and 22 percent in 2021, in turn shrinking regional sales tax revenue. Compared with MTA’s February 2020 forecast (again adjusted for city fiscal years), IBO’s projections for this tax are $138 million (13 percent) lower in 2020, $187 million (17 percent) lower in 2021, and $142 million (13 percent) lower in 2022.

Petroleum Business Tax.While a portion of the petroleum business tax is allocated to the MMTOA Account, there is a separate distribution in MTA budgets that is also referred to as a standalone petroleum business tax. This category includes taxes on the petroleum industry, gasoline and diesel fuel excise taxes, and vehicle and driver license fees

Adjusting for city fiscal years, the MTA in its February 2020 financial plan forecast PBT revenue of $644 million in 2020, dropping to $628 million in 2021, and $618 million in 2022. The preliminary 2020 total for PBT revenue received by the MTA is $594 million, $50 million (8 percent) below the MTA’s February projections. IBO forecasts PBT revenue of $540 million in 2021 and $581 million in 2022—$88 million (14 percent), and $37 million (6 percent), respectively, below the MTA’s adjusted forecasts.

Payroll Mobility Tax and Replacement FundsIn response to a dramatic decline in RPTT and MRT revenues in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, in 2009 New York State approved the payroll mobility tax (PMT), a surcharge on wage income in the MTA region, dedicated to funding transit. Over time the scope and level of the tax have been reduced, and the state annually appropriates additional funds (currently $244 million per year) to compensate the MTA for the loss in income.

The PMT provided around $1.5 billion in funding for the MTA in 2019, and in its February 2020 Financial Plan, the MTA projected that the tax would generate roughly $1.6 billion in 2020 and $1.7 billion a year in both 2021 and 2022 (numbers adjusted to city fiscal years). With job losses in the hundreds of thousands in the city and suburbs, payrolls and wages are expected to fall sharply, eroding the base of the PMT through at least 2021. Preliminary total PMT revenue received by the MTA for 2020 is $43 million (3 percent) below what the MTA had forecast in February. IBO projects that the PMT will bring in just under $1.4 billion in 2021, and just over $1.5 billion in 2022. Compared with the MTA’s February 2020 forecast and adjusting for city fiscal years, IBO’s PMT forecast is $274 million (16 percent) lower in 2021 and $194 million (11 percent) lower in 2022.

MTA Aid. These revenues are also referred to as the MTA Aid Trust Revenues. They are a series of taxes and fees instituted concurrently with the payroll mobility tax in 2009. They consist of supplemental motor vehicle license and registration fees, a tax of 50 cents on hailed vehicle trips within the MTA commuter district region, and a tax of 6 percent on passenger car rentals in the MTA commuter district region.

The MTA’s February 2020 Financial Plan projected that revenues from these taxes and fees would reach $378 million in 2020, and remain fairly constant, at around $320 million per year, in 2021 and 2022. More than two-thirds of MTA Aid revenue comes from license and registration fees. While the number of hailed vehicle trips in the region has been declining, increases in other components of the trust revenues were assumed to compensate for the drop in the hailed ride tax.

The Covid-19 pandemic has heavily reduced traditional taxi ridership and e-hails, as well as car rentals. However, as the economy reopens, more riders are likely to choose taxis and rental cars over conventional mass transit. The preliminary total of MTA Aid for 2020 is $344 million. IBO projects MTA Aid of $274 million in 2021, rising to $320 million in 2022, the same level forecast by the MTA.

For-Hire Vehicle Surcharge.The for-hire transportation surcharge (FHV Surcharge) is a fee on trips taken by traditional taxis, car services, or app-based service such as Uber or Lyft, that begin, end, or pass through Manhattan south of 96th Street. The surcharge is $2.75 for app-based services, $2.25 for traditional taxis and car services, and $.75 per passenger in “pooled” vehicles. Adjusting for city fiscal years, the MTA in its February 2020 Financial Plan projected FHV Surcharge revenue of $417 million in 2020 and $385 million in 2021 and 2022. Preliminary actual revenue for 2020 was $384 million, and IBO projects revenue of $332 million in 2021 and $365 million in 2022. For the entire 2020-2022 period, actuals plus IBO’s projections are$106 million (9 percent) below the MTA’s February forecast.

Internet Marketplace Tax.The internet marketplace tax took effect in New York in calendar year 2019, but its full impact on MTA finances will not come until city fiscal year 2021. The legislation authorizing the tax requires third-party retail sites such as Amazon and eBay to collect and remit sales tax on purchases made by New York State residents. Most of the revenue from the tax is earmarked for the MTA’s capital program, with the rest allocated to local governments. The MTA in its February 2020 Financial Plan projected that it would receive around $213 million from the tax in city fiscal year 2020, rising to $302 million in 2021, and $324 million in 2022. Actual preliminary collections for 2020 were $156 million, well below what the MTA had forecast. The difference may be due to initial set-up or compliance issues. Given the strength of online sales in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, IBO has not adjusted the projected revenue from this tax in 2021 and 2022

The Big Picture

The preliminary total of actual dedicated tax revenue received by the MTA in 2020 is $6.4 billion, $484 million (7 percent) below what the MTA projected in its February 2020 Financial Plan. IBO projects dedicated tax revenue for the MTA of $5.7 billion in 2021 and $6.5 billion in 2022. Compared with the MTA’s February forecasts, these projections are $1.4 billion (25 percent) and $816 million (11 percent) lower, respectively. Over the entire three-year period, preliminary actuals plus IBO’s forecasts represent a drop of $2.7 billion in revenue compared with what the MTA anticipated just a few months ago.

Trouble Ahead, Trouble Behind

Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, the MTA was facing multiple financial challenges related to both its operating and capital budgets. However, the MTA now finds itself in an existential crisis, with ridership expected to be depressed until a treatment or vaccine for Covid-19 is available, revenues hammered by lost customers and a shrunken tax base, and increased costs to make the system safer. Dedicated tax revenues are in important part of the MTA’s overall financial picture. In the past 12 years, New York State has repeatedly had to come up with new revenue sources to keep the MTA solvent. In 2009, the state adopted the payroll mobility tax; in more recent years, Albany has added in taxi surcharges, new taxes on real estate activity, and (yet to be implemented) congestion pricing to keep the trains and buses running.

Given the recession, however, implementing new taxes and fees is unlikely to be a feasible way of stabilizing the MTA’s finances and calls for the city to provide more direct aid to cover the MTA’s operating expenses are likely to increase. This would present a formidable challenge to the city, which under the latest state budget agreement is already committed to providing around $100 million in additional annual funding for the Access-a-Ride paratransit program operated by the MTA, as well as $3 billion for the MTA’s 2020-2024 capital program. While that capital expenditure will not take place immediately, and in fact, much of it may occur after 2024, the city is also still obligated to contribute the $1.9 billion that still remains of a $2.7 billion commitment for the MTA 2015-2019 capital program.

Report prepared by Alan Treffeisen

Endnotes

1Unless otherwise noted, all MTA forecasts cited in the text or displayed in charts have been adjusted to conform to city fiscal years, which begin July 1 of the prior calendar year and run through June 30. The MTA in its reports uses a fiscal year that is equivalent to the calendar year.

2The mansion tax is the only tax dedicated to the MTA for which the Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) issues a forecast. In April, OMB projected that the mansion tax would yield $160 million in 2020, $120 million for 2021, and $171 million for 2022. These projections are well below the preliminary actuals for 2020, as well as IBO’s latest forecasts for 2021 and 2022. At the end of May, OMB made a sharp downward revision to its 2021 forecast of the portion of RPTT that directly funds the city budget, but did not publish a revised forecast of the mansion ta

PDF version available here.