Featured Resources

Fiscal Brief

March 2020

The Governor Says Localities Have Let Medicaid Costs Climb:

State Decisions, Enrollment & Claim Trends Tell a More Complicated Story

PDF version available here.

Summary

In the weeks before Covid-19 upended the health care landscape across New York and the nation, Governor Cuomo proposed finding a total of $2.5 billion in cuts to Medicaid spending to help close the state’s $6 billion budget gap. He appointed a panel of industry stakeholders to make recommendations for the upcoming state fiscal year 2021 budget.

Along with the panel’s savings recommendations, which have not yet been adopted, the Governor also has proposed changes to a cap that limits how much the city and other localities must pay towards annual Medicaid service costs. It also includes state budget language that would make it possible for New York State to withhold the enhanced federal funding the city receives for covering childless adults. These changes, which the de Blasio Administration says could cost the city upwards of $1 billion or more in 2021, on top of the roughly $5 billion it already spends each year for Medicaid services, are necessary according to the Governor because localities have been too willing to allow Medicaid rolls to grow when it has no impact on their budgets. An examination of statewide Medicaid enrollment and claims patterns in recent years tells a more complicated story. Among our findings:

The Governor’s proposal to contain Medicaid costs by lifting the cap on local Medicaid spending presumes that the city and other localities have the ability to control health care costs, particularly for long-term care. Yet it is federal and state regulations that determine Medicaid eligibility, benefits, program design, and reimbursements. For managed long term care in particular, which has been the main driver of recent New York City Medicaid claims growth, it is the state contractor, Maximus, that determines eligibility in most instances.

Medicaid Redesign, Again

Governor Cuomo’s Executive Budget, which was released in January 2020, assumed that the state’s fiscal year 2021 budget had a deficit of roughly $6 billion if no actions were taken to bring spending and revenues into line. The Executive Budget included a number of proposals to slow state spending on Medicaid, including one that would increase the city’s share of the cost of Medicaid spending for services in New York City by hundreds of millions of dollars. Other actions included a 1 percent across the board cut in Medicaid spending for the current state fiscal year and reconvening a panel of experts—the Medicaid Redesign Team (MRT II)—charged with finding $2.5 billion in Medicaid savings for the upcoming state fiscal year. The 1 percent cut will not directly affect the city budget, although it is estimated to reduce Medicaid revenue for the city’s public hospital system by roughly $20 million in city fiscal year 2020 and $45 million in 2021.

On March 19, 2020, the MRT II released a summary of proposals designed to achieve $1.65 billion in savings from Medicaid in state fiscal year 2021; along with measures already outlined in the state’s Medicaid savings plan, Medicaid savings for the upcoming state fiscal year would total $2.5 billion. It is unclear which of these recommendations will be implemented, however, as the proposals still have to be approved by the State Legislature. The Covid-19 relief package signed by President Trump on March 18 further complicates the state budget negotiations over Medicaid, all of which leaves the city uncertain as to what its Medicaid costs will be.

The federal legislation temporarily increases the share of Medicaid costs that are paid by the federal government from 50.0 percent of the total to 56.2 percent to help cover health care costs associated with the coronavirus outbreak. But the bill also included a clause limiting the states’ ability to adjust their Medicaid programs, which could prevent some of the redesign team’s savings recommendations from being implemented. The legislation also includes language that may limit the state’s ability to shift costs onto localities, a proposal that was part of the Governor’s Executive Budget.

The onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, with rapidly escalating health and fiscal impacts, has deepened the state’s challenge in crafting a state fiscal year 2021 budget and increased the importance of Medicaid funding in those negotiations. In turn, this adds to the city’s uncertainty regarding how much it can expect to spend for its share of total Medicaid expenditures

Unlike most states where Medicaid is funded solely by the state and federal governments, New York’s Medicaid program requires localities to share the cost of the nonfederal portion of Medicaid spending. Beginning in state fiscal year 2015, the state agreed to take over 100 percent of Medicaid services spending growth from local government. This turned New York City’s local Medicaid contribution for services, $5.4 billion—which nets to approximately $5.0 billion after accounting for additional federal funding for childless adults—into a fixed cap that is no longer tied to actual spending on services. Despite the cap, it remains a significant burden for New York City and other localities in the state.

Based on the 30-day amendments for the Governor’s Executive Budget, counties that hold property tax growth under 2 percent would be responsible for any increases in the local (nonstate) share of Medicaid costs that exceed the state’s so-called Global Medicaid Growth Cap in a given year. The cap, which was enacted in 2012, limits the growth of state Medicaid expenditures subject to the cap to the 10-year rolling average of the medical consumer price index; for this year, the global cap is roughly 3 percent. Counties that hold Medicaid spending growth under the global cap would receive 25 percent of the “savings.” For local governments that exceed 2 percent growth in their property tax collections—New York City is almost certain to fall into this category every year—not only would the locality be responsible for the entire increase in local Medicaid spending, but any spending over the cap will be added to create a new base level of Medicaid spending for the following year. As a result, even if the locality’s property tax receipts were to increase by less than 2 percent the next year, the locality would still be paying more for Medicaid because of the increase built into the base.

If enacted, the Governor’s Medicaid proposal would take effect in state fiscal year 2021, which begins April 1, 2020. The impact of the proposal on the city budget would depend on the actual growth of local Medicaid spending under the Medicaid global cap, beginning in state fiscal year 2021. The de Blasio Administration estimates that this proposal could cost the city an additional $518 million in city fiscal year 2021 and $1.1 billion the year after, assuming Medicaid spending in the city subject to the global cap rises by roughly 7 percent a year.1 In contrast, the state’s Division of the Budget has cited a figure of $221 million based on the assumption that increases in city Medicaid spending next year will slow to the global cap rate of about 3 percent.

Assuming that MRT II can identify changes to control costs, it is likely that the cost to the city in 2021 will be less than the $518 million estimated by the de Blasio Administration, but still total hundreds of millions of dollars. However, as noted earlier, the legislation signed by the President on March 18, which makes the temporary increase in the federal funding share for Medicaid contingent on states not adjusting their Medicaid programs. Thus, it remains unclear if the state will pursue this cost-shifting option this year.

Additionally, the city also contends that the most recent version of the state budget language would make it possible for New York State to withhold all of the enhanced federal funding the city receives under the Affordable Care Act for covering childless adults—about $487 million—as well as over $100 million in funds from prior year reconciliations.

The Governor’s proposal is based on the assumption that since 2015, when the local spending cap was put in place, localities no longer have an incentive to constrain growth in Medicaid enrollment or to be judicious in approving services. Under this logic, making localities bear some of the costs of continued Medicaid growth should alter localities’ behavior. But this assumption only holds if localities actually play a major role in determining eligibility and approving services.

In an attempt to assess the state’s argument for having localities bear more of the Medicaid burden, IBO used state Medicaid data to identify the groups in the Medicaid population that are growing the fastest and/or have the highest per beneficiary costs, and then discuss the contributions of state policy to these trends.

Given that the impact of the proposed changes are likely to fall disproportionately on New York City, we also examine how much of the statewide growth in Medicaid is attributable to the use of Medicaid in the city versus the rest of the state. In 2018 (all years are calendar years unless otherwise stated), most of the state’s Medicaid beneficiaries (nearly 60 percent) were in New York City and the city accounted for a commensurate share of Medicaid claims.

Major Medicaid Policy Changes, 2011-2019

In 2011, Governor Cuomo appointed the original Medicaid Redesign Team of health care stakeholders to develop a series of cost controls to keep the state’s growing Medicaid budget in check. While the reforms did not include any changes in eligibility or major changes in benefits, limits were introduced for some services. The plan also included mandatory enrollment in managed care for some high-cost enrollees and the shift of some high-cost benefits from fee-for-service to managed care. Most notable was a requirement that ‘dual-eligibles” (Medicaid enrollees who also receive Medicare benefits) who require 120 days or more of community-based long term care services must enroll in a Medicaid managed long term care plan. This transition started in 2012.3

In 2014, the state opted to expand Medicaid coverage as part of the federal Affordable Care Act, which provided federal funds to largely cover the cost of enrolling uninsured individuals whose incomes were low but still above the previous Medicaid eligibility threshold. Starting in 2016, the state also began phasing in a higher minimum wage, raising wages of low-paid Medicaid funded providers, such as home health and personal care aides, but making it more difficult to stay within the global spending cap.

Enrollment Growth and Spending: New York City vs. the Rest of the State

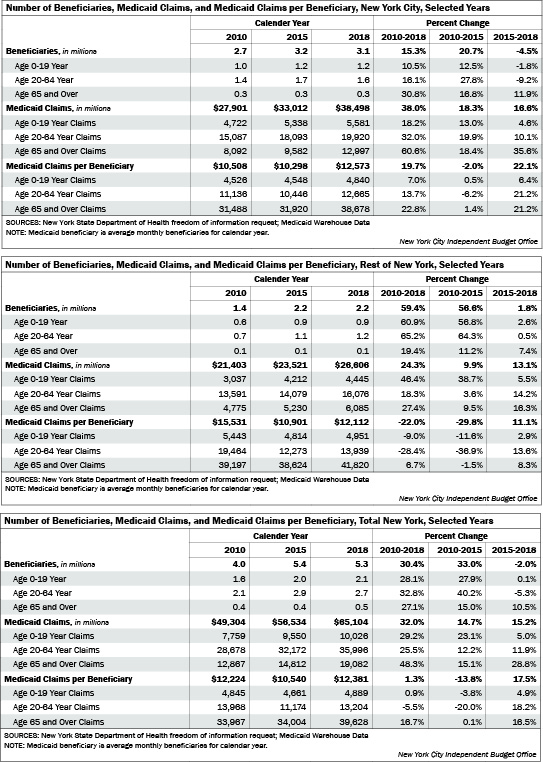

Trends in Medicaid Beneficiaries. From 2010 through 2015, the average number of Medicaid beneficiaries across New York State (Medicaid enrollees who receive health care services in a given month) increased by 33.0 percent, from 4.0 million in 2010 to 5.4 million in 2015, while total Medicaid claims increased by only 14.7 percent over the same period. The relatively slow growth in claims compared with the rapid increase in beneficiaries primarily resulted from trends occurring outside of New York City.

Within the city, increases in the number of beneficiaries from 2010 through 2015 (20.8 percent) were largely in line with increases in claims (18.3 percent). In the rest of the state, however, the number of Medicaid beneficiaries rose more than five times faster than the dollar value of claims, increasing 56.6 percent and 9.9 percent, respectively. Most of the increase in beneficiaries occurred between 2013 and 2014, as enrollment expanded under the Affordable Care Act. This expansion brought large numbers of individuals under the age of 65, a population with relatively low medical costs, onto the Medicaid rolls. As a result, the average cost per Medicaid beneficiary statewide decreased from $12,224 in 2010 to $10,540 in 2015.

During the more recent 2015 through 2018 period, however, growth in the number of Medicaid beneficiaries slowed statewide, the result of an improving economy and the state transferring some Medicaid recipients to the Essential Plan, a low cost non-Medicaid health insurance option under the Affordable Care Act. The number of Medicaid beneficiaries in the city actually fell, while beneficiaries in the rest of the state increased by only 1.8 percent. The amount of Medicaid claims continued to increase, however, pushing up the statewide cost per beneficiary from $10,540 in 2015 to $12,381 in 2018.

Trends in Medicaid Claims. Aggregate Medicaid claims have grown faster in New York City than in the rest of the state. From 2010 through 2018, claims in the city increased by 38.0 percent, from $27.9 billion to $38.5 billion; elsewhere in the state claims increased by 24.3 percent from $21.4 billion to $26.6 billion. Looking at the 2015 to 2018 period, there is less difference in the increase in claims between the two regions. For the city, claims grew by 16.3 percent and by 13.1 percent in the rest of the state.

The disparity between the two regions varies substantially by age group. Among children through age 19, from 2010 through 2018 the increase in claims was larger in the rest of the state (46.4 percent) than in New York City (18.2 percent), due to the larger increase in the number of child beneficiaries outside of the city. Among adults age 20 through 64, the rise in total claims was greater in the city (32.0 percent) than outside of the five boroughs (18.3 percent). The biggest divergence, however, was among beneficiaries age 65 and over, with claims growing by 60.6 percent in the city compared with 27.4 percent in the rest of the state.

Much of the growth in claims among Medicaid beneficiaries aged 65 and over in New York City is attributable to increasing expenditures for providing long-term care, including increased utilization of managed long term care and personal and home health aide services. Over 80 percent of beneficiaries aged 65 and older are dual-eligibles enrolled in both Medicaid and Medicare. Dual-eligibles tend to be the highest-cost Medicaid beneficiaries as they typically have health needs that require heavy utilization of high-cost services including inpatient and long-term care; they typically rely on Medicaid to pay for long term care services not covered by Medicare.

In order to slow the growth in long term care costs for certain dual-eligibles, integrate services, and improve health outcomes for individuals receiving community-based long term care services, in 2012 the state Medicaid Redesign Team required heavy users of these services to transition into long-term Medicaid managed care. Although initially seen as a means of controlling costs, there is little evidence that this initiative has succeeded in constraining the cost of long-term care.

From 2012 through 2018, Medicaid managed long term care claims in the city quadrupled from $2.4 billion to $10.3 billion, increasing from 8.8 percent of total New York City Medicaid claims to 26.6 percent.4

In contrast, mainstream managed care claims grew by 55.5 percent. During this period the number of city beneficiaries 65 and older increased by 23.4 percent.

Given the differences in the composition of the Medicaid caseload between New York City and the rest of the state, it is useful to compare claims per beneficiary for each age group. There are marked differences in Medicaid unit costs for providing health care to different age groups. In 2018, the average per beneficiary cost for adults ($13,204), was more than twice as high as for children, and average costs for individuals 65 and over was nearly eight times higher.

While unit costs have been rising faster in the city than elsewhere in the state, New York City still has lower unit costs in each age category. From 2010 through 2018, average claims per child beneficary increased by a relatively modest 6.9 percent in the city (from $4,526 to $4,840), while decreasing by 9.0 percent (from $5,443 to $4,951) elsewhere. For adults under 65, average claims in New York City increased by 13.7 percent (from $11,136 to $12,665), but decreased by 28.4 percent (from $19,464 to $13,939) in the rest of the state. For both of these age groups, declines in unit costs outside the city were driven by the substantial increase in beneficiaries from 2010 through 2015; average claims have been rising since then.

The pattern was different for the 65 and over group. In 2010, the average claim per beneficiary for older adults outside of the city ($39,197) was 24.5 percent higher than for those in the city ($31,488). Since then average claims increased faster for New York City beneficiaries, reaching $38,678 in 2018, which is still 8.1 percent lower than in the rest of the state ($41,820).

Implications

The rest of the state added about 400,000 more beneficiaries from 2010 through 2018 than did the city, although the story varies depending on the group under consideration. The rest of the state added more children and adults under 65 than did the city, while the city added more beneficiaries over the age of 65. From 2010 through 2018, overall Medicaid claims increased by 38.0 percent in New York City compared with 24.3 percent for the rest of the state. However, since 2015 the difference has narrowed. The biggest difference in spending rates between the two regions is for beneficiaries age 65 and over, although the difference has narrowed in recent years.

The primary driver of Medicaid spending increases among older New York City residents has been the rising cost of providing long-term care. The Governor’s proposal to contain Medicaid costs by lifting the cap on local Medicaid spending is—to a large extent—based on the notion that New York City officials have the ability to substantially control these costs, and would be incentivized to do so by the threat of an increased Medicaid cost burden.

However, it is not clear how much control city officials have over these costs, particularly for managed long term care, which has been the main driver of New York City Medicaid claims growth in recent years. Rules governing Medicaid eligibility, benefits, program design, and reimbursement—beyond those fixed by the federal government—are determined by the state. In addition, the state policy of mandating the shifting of certain dual-eligible users of long term care services into Medicaid managed long term care, along with the shift of high-cost long term services from fee-for-service into managed long term care, does not seem to have slowed the growth in New York City’s managed long term care costs, which grew by 398 percent from 2012 through 2018. By 2018, 32.5 percent of Medicaid enrollees age 65 and over in New York City were in managed long term care, and another 11.9 percent were in mainstream managed care.

In most cases, managed long term care eligibility determinations are conducted by a vendor for New York State, Maximus. While localities still process Medicaid fee-for-service home care service eligibility, localities only process Medicaid home care claims when persons deemed eligible for managed long term care have an urgent need for home care. Such approvals are limited to a maximum of 120 days. Beneficiaries approved for home care under this expedited process must then apply through the regular state-run process for managed long term care within 60 days. For those enrolled in managed long term care, responsibility for service eligibility decisions and claims processing has transitioned to managed care organizations operating under state contracts. Thus, even with more “skin in the game,” the city is limited in its ability to slow increases in the cost of managed long term care, which has been the primary driver of New York City Medicaid cost increases in recent years.

Prepared by Melinda Elias

New York City Indpendent Budget Office

Endnotes

1The assumption of 7 percent, used by the Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget, is based on the actual growth rate of the nonfederal (local and state) global Medicaid cap between state fiscal year 2018 and 2019.

2Unless noted otherwise, the data in this report is based on Medicaid Warehouse Data obtained via a state Department of Health freedom of information request. Medicaid Warehouse data includes Medicaid claim payments paid within the Medicaid claiming system (eMedNY).

3This mandate does not apply to nondual-eligibles, dual-eligibles under age 21, and dual-eligibles not in need of 120 days of community-based long-term care support services. Persons who would be managed long term care eligible but are exempt from this mandate include Medicaid recipients seeking only housekeeping services, Medicaid recipients enrolled in New York State’s nursing home transition and diversion waiver, traumatic brain injury waiver, Medicaid persons under the State’s Office for People with Developmental Disabilities, or hospice program.

4Analysis of MARS39 Report Data for New York City.