Featured Resources

Fiscal Brief

May 2021

Sick Leave Usage:

The Effect of Covid on the Municipal Workforce During the Pandemic’s Peak

PDF version available here.

Summary

New York City’s first confirmed case of Covid-19 was in early March 2020. By the middle of the month schools were closed and the de Blasio Administration had authorized a temporary telework policy for those in the municipal workforce able to do their jobs from home. The Mayor also created an excused leave for staff who were exposed to Covid or who fell ill from the disease. This was important for many city workers: while “uniformed” staff—police, firefighters, sanitation workers, and correction officers—get unlimited sick leave, the “civilian” portion of the workforce do not.

This report looks at the pandemic’s effect on the municipal workforce as reflected in employee leave usage during the peak months of Covid’s initial spread—from March through May 2020. Among our key findings:

New York City employees unable to work remotely, especially uniformed staff, experienced much greater levels of health leave at the height of the pandemic than city workers who could work at home. The need for the city to continue to provide essential services often conflicted with the need to ensure the health and well-being of the municipal workforce.

New York City reported its first confirmed cases of Covid-19 in early March 2020, though later analysis has determined that the virus had reached the city several weeks earlier. By the time Mayor de Blasio ordered the closure of city schools in mid-March, the city was well on its way to becoming the epicenter of the pandemic in the United States. As of April 2021, over 32,000 New York City residents had died from the virus, while hundreds of thousands had been diagnosed with the disease.

One of the myriad challenges the city had to manage during the first wave of the pandemic was ensuring that public services continued to operate while providing for the health and safety of the over 300,000 public servants charged with executing those duties. This brief looks at the pandemic’s effect on New York City’s workforce as represented by employee leave usage during the peak months of the contagion’s initial spread—March through May, 2020.

As a first step towards reducing the spread of the pandemic through the municipal workforce, Mayor de Blasio approved remote work for 10 percent of city employees.>1 Because of the essential nature of many city services including sanitation, police, fire, and emergency medical services, the remote work model was not feasible for a large number of city employees. Other essential functions such as benefits administration, probation monitoring, and budget management were critical to the continued functioning of the city but could be conducted remotely provided work processes were modified.

Thousands of city employees have contracted the virus since early March, while hundreds lost their lives.2 Owing to the risks associated with certain job titles and how those jobs are performed, some groups of city employees were affected more than others. IBO examined the impact of the pandemic on different components of the city workforce.

Timeline of New York City’s Pandemic Response

On March 7, the Department of Citywide Administrative Services (DCAS) issued a directive that the city would provide any employee at high risk of contracting Covid-19 up to 14 days of “excused absence” that would not be charged to the employee’s leave bank. DCAS initially used federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines in designating which employees were in this risk category. They included individuals traveling from Hubei Province, China and those living in the same household as someone with laboratory-confirmed Covid-19. For these two groups, 14-day quarantine was compulsory.

For asymptomatic persons traveling from other high-risk nations or having close contact with symptomatic infected individuals, quarantine was suggested but not required. In this initial guidance, isolation was not required or suggested for those briefly sharing an indoor space with an infected person. These guidelines were later modified to reflect an evolving understanding of the virus’s prevalence and ways in which it is transmitted.

On March 13, DCAS announced a temporary telework policy encouraging at least 10 percent of the city workforce to work remotely. On March 15, with mounting evidence of widespread community transmission, Mayor de Blasio announced the closure of all city schools. While certain Department of Education (DOE) employees would continue to report to their work sites, as of March 15, the majority of the department’s employees were mandated to work from home.3

As the virus spread, the city’s workforce strategy shifted from accommodating employees who contracted Covid to an aggressive plan for social distancing. On March 19, DCAS instructed agencies to designate employees as either essential or non-essential, and separately as either eligible or ineligible for remote work. The city categorized employees providing essential services into four groups:

With the exception of additional support staff for essential services workers incapable of performing their work at home, DCAS instructed agencies to designate all other city employees as non-essential. Although it is likely that the ability to work remotely led to less employee Covid-leave usage than would have otherwise occurred, DCAS did not provide IBO with the data necessary to confirm this.

Covid-19 and the City Work Force—the Big Picture

April 2020 saw the peak of the first wave of Covid-19 cases in New York City. The high point for the seven-day trailing average of new cases in this first wave occurred on April 8, with just over 5,600 new cases reported in a single day. IBO examined the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the city’s workforce by analyzing employees’ leave taking from the onset of the coronavirus pandemic in early March to the passing of the first wave of illness by the end of May. Hours of sick and excused leave taken by city employees, which together are referred to as “health leave” in this brief, peaked on April 11, just three days after New York City’s daily caseload high.4

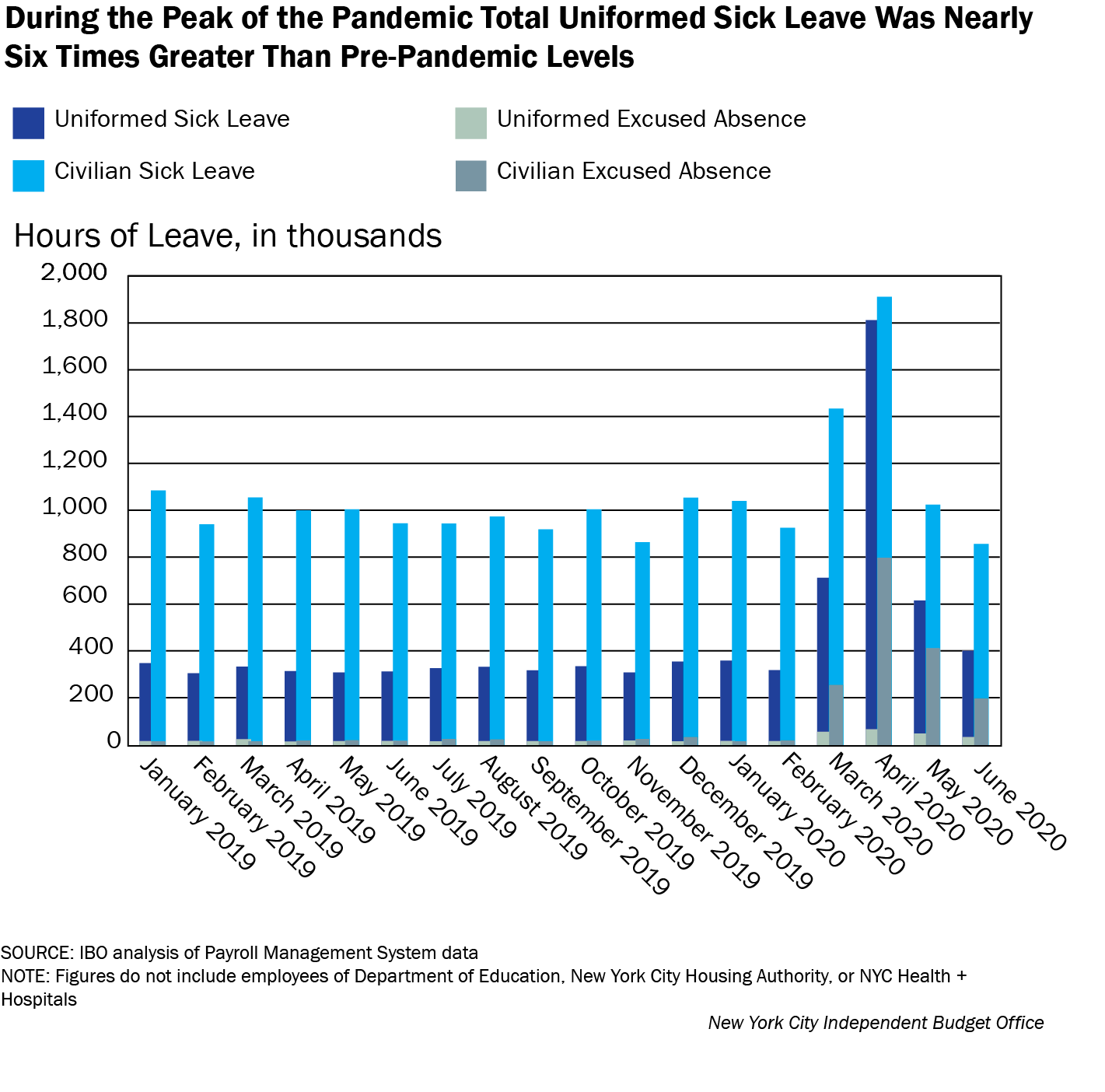

IBO examined leave usage as recorded in the city’s Payroll Management System for approximately 200,000 city employees between January 2019 and July 2020. Because the impact of the virus was felt most intensively in April, we primarily focus on comparing employee leave during April 2020 with leave in April 2019. Employees at the Department of Education, the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), and New York City Health + Hospitals (H+H), which use separate systems to track leave usage, were not included in the analysis.

Exposure to the novel coronavirus, and the likelihood of a municipal employee taking health-related leave during the pandemic, varied across agencies. Uniformed employees, particularly those in the police (NYPD) and correction (DOC) departments, who are eligible for unlimited sick leave, were far more likely to use leave and were out longer than employees serving in non-uniformed titles with more limited sick leave benefits. Public health and other essential employees not considered uniformed by the city—including nurses and Emergency Medical Services (EMS) personnel—also had higher-than-average health leave usage in April, although less than that of uniformed employees. Employees in management titles or those performing work that typically has little interaction with the general public used less health leave than usual and less leave than all other municipal employees in April 2020.

Analyzing Impacts

In the months leading up to the pandemic, leave usage by city employees closely mirrored the usage during those same months in 2019. Once the virus began its rapid spread, however, the patterns of leave usage diverged sharply. Hours of total leave taken by city employees rose by approximately 50 percent as widespread community transmission began in mid-March. This increase was driven almost exclusively by two types of health leave—sick leave and excused absence leave. DCAS’s authorization for employees to quarantine at their homes for 14 days is recorded as an excused absence leave that does not reduce civilian sick leave balances.

This greatly increased use of health leave masks a corresponding drop off in other personal leave. Paid time off—including regularly accrued annual leave and compensatory time in lieu of overtime—was down 41 percent when comparing April 2020 with April 2019. In a typical year the city would experience an uptick in employee usage of personal leave during the week of city schools’ spring break. With the cancellation of the 2020 spring recess in mid-April and the travel limitations brought on by the nationwide quarantine, personal leave usage instead declined sharply. The decrease in the use of personal leave is most evident at the point when health care usage for 2020 begins to mirror usage in the preceding year, towards the end of May 2020. At that point the entirety of the difference between total leave usage for 2020 and 2019 results from the reduction in personal leave taken by city employees, both in paid time-off categories like annual and compensatory time, as well as in other categories like mutual exchange of tours (used in the fire and correction departments), lateness, and worker’s compensation. On the week of June 4, 2020, city employees used nearly 57,000 fewer hours of personal leave than they did in the same week in 2019.

To make sense of the results, it is helpful to divide the city workforce into more categories based on the profile of employees and the work they perform. IBO found meaningful differences in leave usage when categorizing employees by uniformed service and collective bargaining unit.

Uniformed and Civilian Employees

Among the different categories of municipal employees, the one factor that most clearly explained the variation in leave usage is whether the employee serves in a civilian or uniformed title. Uniformed employees, particularly officers of the NYPD, were more likely to take leave and take more leave than other city employees during the height of the pandemic’s first wave in April 2020.

Civilians—a category that encompasses all non-pedagogical, non-uniformed employees—typically accrue both annual and sick leave on a monthly basis determined either through collective bargaining or, for non-union employees, through Mayoral Personnel Orders. City-employed health care workers, including nurses and emergency medical technicians (EMTs), are considered to be civilian workers rather than uniformed; as civilians, EMTs do not receive unlimited sick leave, instead accruing it on a monthly basis.

In contrast, uniformed employees—police officers, firefighters, sanitation workers, and correction officers and their supervisors—have access to unlimited sick leave. With the certification of agency-approved physicians, uniformed employees can remain on paid sick leave indefinitely. In the case of an infectious disease like Covid-19, a uniformed agency’s medical unit must clear employees on sick leave for safe return to work.

Leave related to Covid-19 was far simpler to track for civilians than it was for uniformed employees. Because civilians have finite amounts of health leave to use, agencies coded civilian Covid leave separately from ordinary health leave. Uniformed employees, however, attributed all health leave during the observation period to unlimited sick leave regardless of whether it was ordinary illness or Covid-related.

Both civilian and uniformed sick leave in the first months of the pandemic far exceeded levels observed in the same months in 2019. Uniformed employees used nearly 1.8 million hours of unlimited sick leave and civilians used 1.9 million hours of health leave in April 2020—nearly triple the combined total from the prior April, when 300,000 hours of unlimited uniformed sick leave and a million hours of civilian health leave were used.

From March through May 2020, 44,648 city employees used at least one day of leave attributed to either unlimited sick leave or an excused absence leave category designated for Covid-19 purposes. Of this total, 22,439 city employees (roughly 17,300 civilian and 5,100 uniformed) used at least one day of excused absence leave relating to quarantine.

On average, civilian employees who utilized excused absence leave used 86 hours of this type of leave during the most intense three-month period of the pandemic’s first wave, approximately 12 workdays for civilian employees, who commonly work 7-hour days. Without access to sick leave once they exhaust their available excused absence leave, civilians who took health leave in March through May used an average of about 110 hours (15 and a half days) of other health or personal leave, paid and unpaid, in the three-month period in addition to Covid-19 leave. Because the average leave is driven up by employees with very severe cases of Covid-19 who were absent for long periods, it is also instructive to look at median leave usage, which more closely reflects the impact of the virus on a typical city employee. Over the three-month period, median Covid-related leave usage by civilian employees was 49 hours, well below the average leave usage of 86 hours.

Uniformed employees comprise only 37 percent of the city’s full time employee population (excluding DOE, NYCHA and H+H employees), but accounted for 61 percent of leave takers among employees studied. Studying leave taking by uniformed employees is difficult because uniformed sick leave is unlimited. Documentation for the reason uniformed employees took health leave is not available in payroll records and therefore we were not able to determine whether leave taken during this period by uniformed employees was necessarily the result of Covid-19.

A total of 27,252 uniformed employees took at least one day of sick leave between the onset of the pandemic in March and the end of May, with nearly 20,000 taking some leave during the initial peak of the pandemic in April. On average, uniformed employees taking sick leave used 126 hours of unlimited sick leave in the three-month period, equivalent to nearly 16 days of sick leave in 8-hour work days, which are standard among uniformed employees. Not surprisingly, the median number of unlimited sick leave hours used by uniformed employees was lower than the average—86 hours versus 126 hours during this period. Uniformed employees who took sick leave also used an average of 16 hours of Covid-19 excused absence leave, less than one-fifth the average used by civilian employees. Compared with civilian employees, uniformed employees also took less of other types of time off, 32 hours (4 days) on average from March through the end of May.

Collective Bargaining Unit

Examining employee leave usage by collective bargaining unit (CBU) provides a way to observe how big a role an individual’s type of work influenced their health during the pandemic. The city’s unionized municipal labor force is grouped into CBUs, which in some cases are a single homogeneous union, like the Police Benevolent Association (PBA), and in other cases a local within a larger union or labor organization such as District Council 37 (DC37). The rights, benefits and work schedules of the workers in each CBU are governed by negotiated contracts in addition to agency policy.

City employees in white-collar positions such as accountants, engineers, and data analysts—many represented by locals in DC 37—averaged nearly the same or less health leave in April of 2020 than in April of 2019. Other office workers also appear to have reduced their health leave usage—attorneys (Civil Service Bar Association), staff analysts (Organization of Staff Analysts), procurement specialists (SEIU Buyers), civilian managers, and other non-unionized administrative employees all used less health leave than in the year prior during the height of the pandemic’s first wave in April. These employees were more likely to be allowed to work from home during the pandemic than those employees in uniformed CBUs. Without a more in-depth analysis, however, we cannot assume that the relative decline in health leave usage by these individuals was solely related to their work situations. The mandated cancellation of elective medical procedures along with the precipitous decline in non-Covid medical visits that occurred citywide are factors that also likely contributed to reduced leave usage by these employees.

The city moved to aggressively expand eligibility to work from home during the pandemic. Non-essential personnel, particularly those who could work remotely, were encouraged to do so in order to improve commuting and working conditions for those who could not. IBO requested information on which job titles were designated as essential/non-essential and which titles were eligible for remote work at the agency level from the Department of Citywide Administrative Services—the agency responsible for coordinating Covid workforce matters—but our request was denied due to privacy concerns. With the data available, however, we are able to see that CBUs representing employees in frontline jobs had higher rates of health leave usage during the peak months of the first wave of the pandemic.

During the height of the pandemic, employees represented by public safety unions with access to unlimited sick leave were far more likely to use sick leave than employees with traditional accrued sick leave balances. In April, uniformed police officers, represented by the Police Benevolent Association, used five times more health leave than they did in April 2019. Police sergeants (SBA) and lieutenants (LBA) used over four times as much leave during this period than the year prior, while detectives (DEA) used three times as much leave, as did corrections officers (COBA). The nature of work performed by police officers necessitates direct contact with the public, increasing their likelihood of contracting or spreading the coronavirus through the community.

Further complicating matters, police officers were given the responsibility of enforcing social distancing requirements early in the pandemic. Overall, 33 percent of PBA members used at least some leave last April; officers who took sick leave used an average of 92 hours during the month.

The non-uniformed CBU with the highest additional leave usage during the height of the pandemic were the associate traffic enforcement agents (TEAs) represented by the Communication Workers of America. Traffic enforcement agents are civilian employees of the NYPD and are often in direct contact with the public on city streets. The city’s TEA’s took over five times the amount of sick leave in April 2020 than they did in the same period last year. Many of the city’s non-uniformed collective bargaining units experienced higher health leave rates as well; Teamsters maintenance workers and school safety agents, and Service Employee International Union auto mechanics all used over twice the health leave in April 2020 in comparison to the prior April.

Due to the diversity of work performed by DC 37 collective bargaining units, leave usage among DC 37 members in April 2020 varied greatly depending on the CBU. Among CBUs with more than 1,000 full-time employees represented by DC 37, those serving in maintenance titles, Emergency Medical Services, and clerical employees averaged more than twice the health leave in April 2020 than workers in those CBUs averaged in the April 2019. EMS workers, despite being employed by the fire department, are not considered uniformed employees and are not eligible for unlimited sick leave. During the height of the pandemic, EMS workers relied heavily on the city’s 14-day excused absence policy. Thirty-two percent of city employees represented by the EMS collective bargaining unit used some excused absence leave in April. Those EMS workers who took leave during April 2020 used an average of 65 hours.

Cost Implications for the City

The city’s decision to provide excused absence leave to employees who contracted coronavirus or had to care for a family member who had the virus had a financial impact on the city. For uniformed employees and many classes of shift- or project-based work schedules, healthy replacements must be assigned to cover for workers unable to work. In agencies with such work schedules, staffing allocations provide for covering normal levels of leave usage, but during the height of the pandemic’s first wave, leave in many of these agencies exceeded normal levels. IBO estimates the cost of all reported excused absence leave and unlimited sick leave in excess of typically observed levels for uniformed employees totaled $152.1 million from March through June 2020.5 The cost-per-hour is calculated as the excess leave used by a worker multiplied by their hourly rate of pay, where “excess” leave is the number of hours of leave used above the average leave usage in the same month of 2019. It is not surprising that the majority of the cost occurred in April, the height of the pandemic, with $27.2 million in excused absence leave granted and $62.4 million in excess uniformed sick leave.

The Mayor’s 2022 Executive Budget published last month allocates $100 million of direct federal aid from the American Rescue Plan Act for “Covid-Related Leaves,” to cover the cost of employees absent while recovering from Covid-19. Given that excess excused absence leave has averaged approximately 100,000 hours per month from July 2020 through May 2021, IBO assumes that the $100 million will not be adequate to cover the entire cost of Covid-related leaves, particularly the excess uniformed leave amounts.

The devastation wrought by the Covid-19 pandemic unfortunately did not conclude in the spring of 2020; while New York City’s infection rates had declined precipitously by the summer, in other areas of the country the virus had just begun its spread. The winter of 2021 brought a second wave to the city with daily case rates matching and at times exceeding those in the first wave. It is clear that in the early months of the pandemic the virus had disproportionate impacts across communities, differentiated by socio-economic status, race, and ethnicity, and type of employment. New York City employees who were unable to work remotely (particularly uniformed employees), experienced much greater levels of health leave at the height of the pandemic than those employees whose situations allowed for remote work opportunities. Employees in traditionally white-collar positions, who were capable of performing remote, computer-based work, used disproportionately less leave in the midst of the pandemic. The need for the city to continue to provide essential services during the height of the pandemic was often in conflict with its need to provide for the health and well-being of its workforce. The careful balancing of these two obligations will play a substantial roll in decisions made regarding the composition and design of the city’s municipal workforce of the future.

Report prepared by Robert Callahan

Appendix

PDF version available here.

Endnotes

1https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/143-20/mayor-de-blasio-provides-on-new-york-city-s-Covid-19-response

2https://www.nydailynews.com/coronavirus/ny-coronavirus-labor-day-deaths-20200907-dvtq2sipcrcgbfnhv4wpvdvd6u-story.html

3https://www.thenation.com/article/society/schools-teachers-Covid/

4IBO defines health leave as sick leave, excused absence, and leave without pay. Personal leave is defined as annual leave, compensatory time, holiday, mutual exchange, lateness, worker’s compensation, and other leave.

5Information on employee salaries was generated in July 2020, meaning that costs may be slightly overstated if employees received any contractually obligated or merit-based pay increases at the conclusion of the fiscal year in June.