Posted by Doug Turetsky, October 23, 2012

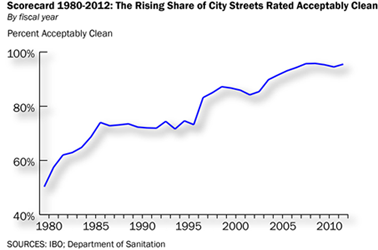

Last month, a Travel & Leisure magazine reader survey ranked New York the dirtiest city in the U.S. Just a few weeks later, the Bloomberg Administration released the Mayor’s Management Report for fiscal year 2012, which found that 95.5 percent of the city’s streets were ”acceptably clean”—meaning there were only scattered bits of litter on the streets. The report deemed not a single section of the city dirty.

Even acknowledging that there can be sharp differences among individual perceptions of intolerable levels of grit, grime, and litter, there’s a huge gulf between the T&L survey and the Bloomberg Administration’s rating. In 2012, the city spent $81 million on activities related to cleaning its streets such as running the city’s 450 mechanical brooms and emptying litter baskets, according to figures provided by the sanitation department. About $570 million more was spent collecting curbside trash and recyclables. Given these expenditures, chalking up that gulf in perceptions solely to eye-of-the-beholder differences seems insufficient—especially since city residents may not see eye-to-eye with the Bloomberg Administration rating either.

In July, the Mayor’s Office of Operations, which does the street cleanliness ratings, scored 98.4 percent of the streets in Manhattan’s Community Board 1 as acceptably clean. Yet Crain’s recently reported that complaints about overflowing trash cans in Lower Manhattan, which is part of Community Board 1, led city officials to add more trash cans in the area in August, the very month following the pristine rating. And now Lower Manhattan’s Downtown Alliance has placed solar powered trash-compacting bins that can hold five times the amount of garbage as a regular litter basket at five heavily trafficked street corners.

Community boards citywide also may be less sanguine than City Hall when it comes to the cleanliness of the city’s streets. As a way to gauge the demand for certain services, the Mayor’s budget office asks community boards each year to rank by importance 90 different services provided locally. Street cleaning ranked 17th citywide, ahead of other efforts such as economic development initiatives, housing code inspections, and services for the homeless.

On a recent Wednesday morning IBO’s Justin Bland and I joined Edwin Cuevas and Alicia Robinson as they rated the cleanliness of about 25 streets in Crown Heights. Each month three teams from the Scorecard program in the Mayor’s Office of Operations rate the same set of 6,900 of the city’s 120,000 blocks. As Robinson drove, Cuevas, a 19-year veteran of the program, eyeballed and quickly rated the cleanliness based on a seven-point numerical scale. To better ensure that the drive-by survey is representative of daily conditions, the week, day, time, and team doing the rating for each set of streets in the sample varies from month to month.

But there are two key reasons the survey findings may not mesh with public perceptions. First, the streets surveyed and the rating scale were developed in the late 1970s, a time when there may have been lower expectations—at least compared with today—for what measured up as an acceptably clean street. Additionally, the surveyed streets may no longer provide the most representative sample. Operations staff members acknowledge that public perceptions of what’s clean or dirty have changed over the years and are working to recalibrate their rating system as well as adjust which streets are surveyed.

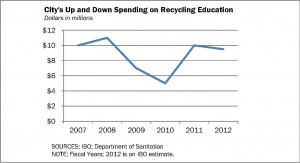

Secondly, the ratings are compiled Monday through Friday. So the survey doesn’t capture a view of street cleanliness on weekends and holidays, when tourists abound and neighborhood commercial streets are busiest and litter most likely to pile up and trash cans overflow. For years, the City Council funded litter basket pick-ups on Sundays and holidays in business districts around the city. But the Council hasn’t provided funds for this service since 2009, when it pitched in $1.4 million.

Reconciling tourist impressions of what’s a clean street with those of New Yorkers may be impossible. For some tourists, the sense that the city’s streets are dirty may be heightened by the crowds and disorder that characterizes street life in some parts of New York, a level of activity that may be alien to their usual experience.

What may be more important is comparing New Yorkers own impressions of street cleanliness with those of the Mayor’s scorecard. Even if the Mayor’s office updates and improves its rating system, putting City Hall’s self-assessment alongside a survey of the views of residents and business owners could be instructive. After all, they’re the ones paying for the service.