Posted by Doug Turetsky, November 10, 2011

An October 26th Daily News article reported that New Yorkers put out less trash for curbside pickup in fiscal year 2011 then they did in 2010. But lower trash levels are not a citywide phenomenon. The one exception: the Bronx.

Some sanitation experts say there’s more trash in the Bronx destined for landfills or incinerators because the borough diverts a comparatively small share of its trash to recycling.

In 2011, the Bronx diverted a paltry 10.3 percent of its refuse to recycling, well below the diversion rate of the other boroughs. Manhattan topped the charts at 19.0 percent with Staten Island a close second at 18.6 percent. Seven of the Bronx’s 12 community districts recycled less than 10 percent of their trash. Of the city’s 47 other community districts, only 6 had recycling rates below 10 percent.

Still, the citywide recycling rate declined overall in 2011 to 15.4 percent from 15.7 percent in 2010. Every borough except Staten Island saw the share of its refuse diverted to recycling fall in 2011. Only 25 of the city’s 59 community districts met or exceeded the citywide goal in 2011 of diverting 16 percent of its trash to recycling. In the same Daily News article, Council Member Letitia James, who chairs the City Council’s sanitation committee, blamed low recycling rates on the city’s failure to adequately educate the public.

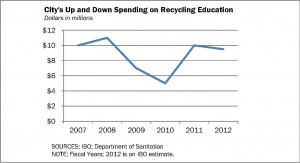

Although the Mayor’s PlaNYC lists several initiatives to encourage recycling, including the expansion of education programs, funding levels for education efforts have varied over time. Numbers compiled by IBO’s Yevgeniya Bukshpun show the extent of the fiscal ups and downs. Spending on recycling education and outreach tumbled from just under $11 million in 2007 to barely $5 million in 2010. It rebounded to nearly $10 million last year but IBO currently projects it to total about $450,000 less than that this year.

Inconsistent funding of education and outreach may not be the only reason many New Yorkers find it hard to know (or care) what should and shouldn’t be recycled. There have also been some abrupt changes in the program.

In an effort to save money, the city temporarily stopped collecting glass and plastic in 2002—only metal and paper were recycled. In July 2003, plastic recycling resumed, but the city temporarily shifted to alternate week pickups of recyclables. For many New Yorkers, this meant letting recyclables collect in their apartments or basements for a couple of weeks—or simply tossing it with the regular trash. Glass was not recycled again until April 2004. Anecdotal evidence such as a peek at neighbors’ recycling cans give an indication there’s still confusion over what is and isn’t recycled.

While more education and outreach programs could relieve the bewilderment over what’s recycled, it won’t address the “slimming down” of some of what is recycled. Sanitation experts generally talk about how much is recycled in terms of the diversion rate: the share by weight of our curbside trash stream that’s set aside for recycling.

Declines in the city’s diversion rate may in part be because recyclables don’t weigh as much as they used to. Some plastics have gotten lighter and newspapers and magazines are shrinking (along with their readership and advertising pages). Some of the drop in recyclables, as well as regular trash, may also be a side effect of the sluggish economy—people are buying and throwing out less.

Perhaps there’s a lesson to be learned from this fall off in curbside trash. While recycling is the “apple pie” of environmentalism, it might make sense to increase the emphasis placed on those other two “Rs” in the litany of environmentally sound trash management practices: reuse and reduce.

As IBO has well documented, it costs more to collect and dispose of a ton of recycling than the city’s regular rubbish, although the gap has been narrowing as the cost of exporting trash to landfills and incinerators has escalated. But stuff that never winds up at curbside for pickup, whether recycling or regular trash, costs nothing for collection and disposal. Of course, additional efforts to decrease the amount of stuff that winds up in the city’s waste stream may take more investment in public education and outreach.