February 2017

If No Student Pays:

Cost to Provide Free Lunch for All of New York City’s Elementary School Students

REVISED

PDF version available here.

Summary

For the past few years, a number of advocates and elected officials have urged the city to provide free lunch to all students in New York’s public schools. They contend that a universal free-lunch program could remove the stigma that may discourage some low-income students from taking advantage of the city’s current program and help ensure that all students are adequately nourished, which is essential for success in school.

In response, the city has adopted a pilot program: free lunch for all students in about 285 middle schools. IBO has looked at the cost of that program in school year 2014-2015 (the most recent year for which there is complete data on lunch participation rates) in order to estimate the cost of providing free lunch to all students in kindergarten through fifth grade. The report describes the three different options the federal government provides for reimbursing schools for meal programs and considers different take-up rates under the assumption that more students would take advantage of a free lunch if all were eligible. Among our findings:

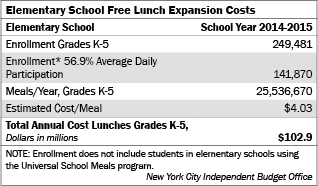

- The cost for school lunches in elementary schools in school year 2014-2015 was $102.9 million, or $4.03 per meal, with about 57 percent of kindergarten through fifth graders participating in the program.

- If the city had offered free lunch to all kindergarten through fifth grade students in 2014-2015 (excluding students who attended a school already offering free lunch to all) under the guidelines of the federal Community Eligibility Program, and participation rates remained constant, it would have cost the city an additional $5.2 million while making free lunch available to nearly 38,500 more students.

- If universal free lunch in the elementary schools increased the rate at which students took advantage of the meals by 10 percent, the additional cost for the city would have been another $4 million. If the participation rate grew by 50 percent, it would have increased the cost by $18 million.

These estimated additional costs for a universal free lunch program in all of the city’s elementary schools are based on current federal guidelines and reimbursement levels. But the future of these programs is uncertain. For example, a bill was introduced in Congress last fall to change the Community Eligibility Program to a block grant. If the amount of the block grant were to fail to grow with increased meal costs and demand, the city could face the choice of contributing more funding or scaling back the program.

The adopted budget for fiscal year 2017 and the preliminary budget for 2018 maintained the status quo regarding access to free- or reduced-price lunch for New York City Department of Education (DOE) students, disappointing advocates who had called for expanding the program to provide lunches for all students and prompting calls for future action.

Advocates for expanded meal programs see a universal meal program as a way to remove the stigma that may discourage many low-income students who qualify for free lunch from using the program. These lunches are generally more nutritious than the options available to families struggling to put food on the table—or in the lunchbox. In this brief, IBO looks at the school lunch program and its current costs, and estimates the cost of expanding one of the federally supported options that are currently being piloted in some middle schools in the city. We also provide estimates of the per-pupil cost of any larger expansion of universal free meals.

Brief History of School Lunch Programs. The forerunners of today’s school lunch rooms began in the early 1900s. At that time a number of private organizations such as the New England Kitchen were starting to advocate for serving lunches in school in places such as Boston.1 Prior to this time, children typically went home for lunch, but as women began to work outside the home a need for school cafeteria lunches began to develop.2 In 1908 a group of concerned women started the New York School Lunch Committee, a charity that operated until the Board of Education picked up the responsibility in 1920.3 Eventually the idea of a lunch break at school was adopted by school districts and schools across the country in various formats but it was not until 1946 that both the lunch program and critical funding were placed into federal law.

The National School Lunch Program was formally established under the Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act of 1946, and signed into law by President Truman. The program served a dual purpose. With the memory of hungry and malnourished children still fresh from the years of the Great Depression, Section 2 of the act stated its intent to “… safeguard the health and well-being of the Nation’s children.” The act also had the benefit of supporting farmers by drawing down large agricultural surpluses.4 Subsequent reauthorizations of the federal school lunch program have sanctioned additional feeding programs with the most recent reauthorization—titled the Healthy, Hunger Free Kids Act—adopted in 2010.5

Free-Lunch Programs in New York City SchoolsThe National School Lunch Program (NSLP) incentivizes both public and private schools across the country to serve lunches to school children. The NSLP includes a number of alternative eligibility and reimbursement models that states and/or school districts can elect to use. Under the traditional school lunch program, students from households with incomes up to 130 percent of the federal poverty threshold qualify for free lunches; those from households with incomes from 130 percent to 185 percent of the poverty threshold qualify for reduced-price lunches, and those from households with incomes above 185 percent pay full price. Under the traditional model schools are reimbursed by the federal government for a portion of the cost for all lunches served, with the reimbursement pegged to the student’s family income.

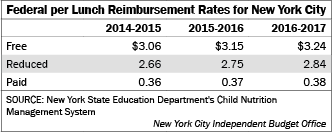

The federal government currently reimburses the city $3.24 for each free lunch served—a subsidy that falls short of the full cost to the city of providing the meal. The federal reimbursement is lower for reduced-price and full-price lunches, $2.84 and $0.38, respectively.6 In addition to this federal reimbursement, which is also supplemented by small state reimbursement subsidies, the city provides its own funds for all meals served in schools regardless of family income.

Two alternatives to the traditional model that are also available under NSLP and used in New York City are Provision 2, which is otherwise known as Universal School Meals (USM) and the Community Eligibility Program (CEP). Although the eligibility criteria differ, both shift the determination of eligibility for free school lunch from individual students to the school as a whole. Qualified schools provide free lunches to every child enrolled in the school, regardless of income.7

Both the traditional school lunch program and the USM rely on the physical collection of lunch forms sent home to parents. The completed forms contain the self-reported household income that is used to establish each student’s income category. The CEP program was established by the federal government in 2010 to improve upon the current data collection process by replacing the use of forms with direct certification based upon an electronic match of student records with other government data to identify those who qualify for free school lunches.

In the current 2016-2017 school year, 383 city schools—roughly 24 percent of all schools—are expected to be eligible for the universal school meals program.8 Under the USM program, as long as 60 percent of a school’s students qualify for free school lunches based on their self-reported income, all students in the school are able to eat for free, regardless of their individual household income. Once a school has met the 60 percent threshold for eligibility, it does not have to collect lunch forms for the next three years. In the fourth year, the school must once again establish eligibility by collecting the forms and hitting the 60 percent threshold. The results of that new round of lunch-form collection becomes the new base year. Out of the 383 city schools currently in the USM program, 36 schools have reached the fourth year of participation and will be required to collect lunch forms this school year.

In school year 2012-2013, school districts in New York State became eligible to take part in the CEP. Following enactment of CEP in 2010, the federal government first rolled out the program in only three states during school year 2011-2012. New York became one of four states to participate in the second phase of the roll-out during school year 2012-2013. All states became eligible for participation in the program during school year 2015-2016.

The Community Eligibility Program allows schools to serve free breakfasts and lunches to all students without having to collect and process individual lunch forms. Although the DOE had already begun serving free breakfast in every school in an unrelated initiative, providing free breakfast is also one of the requirements for participation in the CEP. Eligibility is determined by the number of students who automatically qualify for free meals because either the student or his or her family has already been found to be eligible for food stamps, cash assistance, or Medicaid. This is known as direct certification. Students are also directly certified and automatically qualify for free meals under CEP if they are in foster care, enrolled in Head Start, homeless, children of migrant workers, or runaways. If the number of directly certified students exceeds 40 percent of the student population, the school or district can participate in CEP. In addition to providing free lunches to all of a school’s students, CEP also reduces the number of reimbursement rate categories from three (free, reduced price, and full price) to two (free and full price). For the 2016-2017 school year, 217 DOE schools (13 percent of all schools) are expected to take part in the program.

Federal Reimbursement for School Lunch Programs

Under the traditional model, lunches served to each student are accounted for daily by eligibility category (free, reduced price, or full price). Federal reimbursement for a particular day is calculated by multiplying the number of lunches served in each eligibility category by the appropriate reimbursement rate for that category and summing over the three categories. Under USM, schools simply take a count of the number of reimbursable lunches served each day and reimbursement is based on the eligibility category shares that were previously determined in the base year.

Federal reimbursement under the CEP program is based on the ratio of automatically qualified students to total enrollment at either the school or district level, multiplied by a factor that is currently set at 1.6. (By law, the United States Department of Agriculture can set this multiplier anywhere between 1.3 and 1.6.) The multiplier is intended to account for low-income students who are not reflected through direct certification. The result becomes the share of lunches that will be reimbursed at the free-lunch rate for each participating school. Given that 40 percent is the minimum portion of directly certified students in a qualifying school, the lowest possible share of meals reimbursed at the free rate is 64 percent in CEP schools. The daily process of manually counting the number of students per category is avoided.

In 2014-2015, 52 percent of total enrollment—more than 500,000 New York City students—met the direct certification criteria under the Community Eligibility Program.9 For each city school participating in the CEP program in 2014-2015, the share of student lunches reimbursed at the highest federal rate ($3.15 per lunch) was 83 percent: the citywide share of automatically qualified students (52 percent) times the multiplier (1.6). The remaining 17 percent of lunches served at CEP schools were reimbursed at the rate for full-price lunches, $0.37 per lunch.

The effect of the differing reimbursement structures is that fewer lunches are reimbursed at the lowest federal rate and more lunches are reimbursed at the highest rate in CEP schools than under the USM model, generating more federal revenue for the Department of Education.

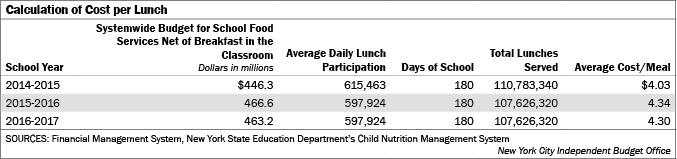

The per Meal Cost of School Lunch

To estimate the average cost of producing a school lunch, regardless of the federal reimbursement method, IBO identified all annual school food and labor costs that could be attributed to lunch service and divided by the total number of lunches served.10 The total number of school lunches served is simply the average number of students who participate in the lunch program each day times 180 school days per year. Average costs increased from 2014-2015 to 2015-2016, driven by a combination of higher input costs and a decline in the number of lunches served. For the current 2016-2017 school year, IBO estimates that the cost of preparing and serving school lunches again increased and will average $4.30 per lunch.

Although the city budget issued in November anticipated a $26.3 million increase in the total cost of food services from $487 million last year to $514 million this year due to a projected increase in the cost of food and higher labor costs for hourly employees, the cost of the breakfast in the classroom has grown by $34 million from $21 million to $55 million—leaving less money in the overall school food budget for lunch. The lower amount projected for lunch expenditures, combined with the decline in the anticipated number of lunches served results in a small decline in the average cost of school lunch from $4.34 per student in 2016-2017 to $4.30 this year.

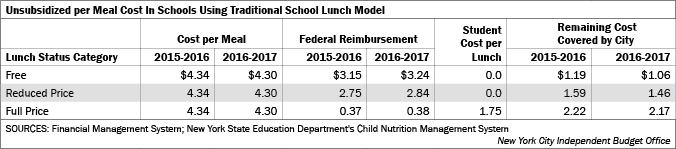

The cost to produce a single school lunch in 2016-2017 is the same under each of the three federal lunch programs: the traditional version of the National School Lunch Program, the Universal School Meals program, and the Community Eligibility Program. However, the extent to which the federal government subsidizes each lunch varies depending on the program used by the city.

Under the traditional NSLP, the federal government will reimburse DOE $3.24 for each free lunch, $2.84 for each reduced-price lunch, and $0.38 for each full-price lunch served in school year 2016-2017; all three reimbursement rates fall short of the average $4.30 it costs DOE to produce a lunch. Students who pay “full price” are charged a $1.75 per lunch fee. Although “reduced price” remains as a category in the federal NSLP, in New York City, the DOE stopped collecting a fee from students whose household income qualified as “reduced price” in the 2015-2016 school year, so that both students eligible for either reduced price or free lunches eat for free. Because of the higher federal reimbursement rates for free and reduced-price lunches, the unsubsidized cost to the city is actually greatest—$2.17 per lunch—for students who pay full price.

CEP Middle School Pilot Program

For a number of years, advocates have called upon the Department of Education to expand access to free school lunches, a policy known as universal free meals, through the Community Eligibility Program. In response, the DOE instituted a pilot program in the 2014-2015 school year in all stand-alone middle schools. With the pilot in place, advocates and a number of elected officials, including Public Advocate Leticia James and City Council Education Chair Daniel Dromm, have called for the education department to expand the free-lunch program from its current pilot to all schools across the city.

Although all schools and districts in New York State became eligible to try the CEP program in calendar year 2012, it was not until the 2014-2015 school year that the city’s DOE began to participate. To test how CEP would work in city schools, a pilot program was implemented to provide free lunch in stand-alone middle schools. DOE budget allocations for the 2014-2015 school year indicate that there were 285 eligible stand-alone middle schools that enrolled 149,524 students.

The DOE reported that gross program costs were $49 million, with federal reimbursement totaling $39 million. This left a net cost of $10 million, of which $6 million was financed by the City Council. In the spring of 2015, additional funding for an expansion of the middle school lunch pilot to all middle schools was added in the Mayor’s Executive Budget for Fiscal Year 2016. At that time the city expected an $8 million increase in federal funding along with $6.5 million in increased state revenue. With these increases in aid, the city’s portion of the pilot program’s cost was reduced by $3.25 million in 2016. These funds were baselined through fiscal year 2019 but it is unclear if funding will continue beyond 2019.

Estimating the Cost of Expanding CEP to All Elementary Schools

To explore the potential costs of expanding the use of the Community Eligibility Program, IBO examined the fiscal impact of bringing the program to all elementary schools in the city except those currently using the Universal School Meals program. Using data for school year 2014-2015, which is the latest with complete data available on school lunch participation, IBO estimated how much it would have cost to use CEP to provide free lunches for (K-5) elementary school students in 2014-2015 based on the school lunch participation rates for that year.

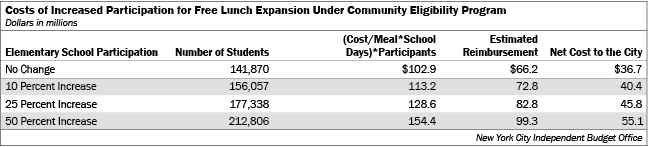

One uncertainty in our analysis is that we do not yet have enough information from the pilot program to project whether the lunch participation rate increases when student lunch fees are eliminated. One of the motivations for expanding the CEP program is to increase participation by removing any stigma associated with being a student receiving free lunch, as all students in a CEP school would be in the same status. We address this uncertainty by generating cost estimates under three possible take-up rates: increases of 10 percent, 25 percent, and 50 percent from the systemwide participation rate that year of about 57 percent.

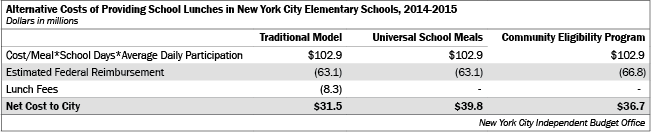

Based on the actual 2014-2015 participation rates, the average number of additional elementary school students participating in the lunch program each day was roughly 141,870, which translates into about 25 million lunches over the school year. Using the 2014-2015 per meal cost of $4.03, the total annual cost of these lunches would be $103 million.

In the traditional lunch model, 73 percent of students qualified for free-lunch status, 6 percent for reduced-price status, and 21 percent were full price. In terms of lunches served over the year, 18.6 million were served to free lunch students, 1.6 million to reduced-price students, and 5.3 million to those classified as full price.

Under the traditional school lunch model, the city would have received a total reimbursement of $63 million ($57 million for the free lunches served, $4.2 million for the reduced-price lunches, and $1.9 million for the lunches served to full-price students). In 2014-2015 the city also collected an estimated $8.3 million in lunch fees paid by reduced-price and full-price students.11

Under the universal meals model, the federal reimbursement would be the same $63.1 million as in the traditional model. However, because all lunches are served at no cost to the students, there would be no lunch fee revenue to help offset the cost of providing the meals. After accounting for the lost lunch fees the net cost to the city under the USM method would be $39.8 million.

For the purposes of estimating the net cost under the Community Eligibility Program in school year 2014-2015, the ratio of cash-assisted students across the DOE to total enrollment was 52 percent, which multiplied by the CEP-allowed multiplier of 1.6 results in a free lunch eligible student share of 83 percent. This means that 83 percent of lunches eaten each day by participating students would qualify for reimbursement at the federal free lunch reimbursement rate with the remaining 17 percent of lunches reimbursed at the federal paid-lunch rate. In this case total federal reimbursement would be $66.2 million and, once we account for the lunch fees that would not be collected, implementation of the CEP model in every elementary school in the city (except for those already participating in USM), would result in a $36.7 million net cost to the city.

If lunch participation rates increased under CEP, the amount of federal reimbursement would grow, but so would the city’s costs net of the reimbursement. For example, a 10 percent increase in participation from 2014-2015 levels would have raised the total annual cost of providing lunches by $10 million, while the federal reimbursement would grow by $7 million, leaving the city’s net cost $4 million higher than if participation were unchanged. If participation grew by 50 percent, the corresponding changes would have been a $52 million increase in the cost of providing lunches and a $33 million increase in federal reimbursement, leaving the net city cost $18 million higher than at 2014-2015 participation levels.

Outlook for Federal School Lunch Funding

The school lunch program has roots that stem back to the early 20th century. What started out experimentally grew over the last century to become a major antipoverty program in the schools. Today the U.S. Department of Agriculture not only subsidizes lunch through the National School Lunch Program, but also operates the school breakfast program, the child and adult care food program, the summer food service program, and the milk program among others. Roughly 1 million New York City schoolchildren benefit from these programs.

New York City receives funding through three federal lunch reimbursement structures, the traditional model, Universal School Meals, and the Community Eligibility Program. The USM and CEP models are both designed to feed every child enrolled at a given school, although they differ as to how much of the cost of those universal lunches is reimbursed by the federal government. All of these federally subsidized programs have strings attached and require various forms of documentation to ensure recipients meet income or eligibility criteria. Just as the government has reauthorized school food programs over the years, so has it modified its reporting criteria to reduce the burden of paperwork requirements. The community eligibility provision is one of the latest efforts.

Despite the fact that many people would like to see the CEP take hold in every school in New York City, the DOE has been hesitant. If the city were to undertake such an expansion of universal free lunch, IBO’s analysis indicates that from a budgetary perspective, CEP would be the most cost-effective approach. Not only are paperwork requirements reduced, but the CEP reimbursement structure, with two rather than three reimbursement rate categories and the 1.6 multiplier, results in a larger portion of students in the highest reimbursement rate category and a higher federal reimbursement for the same number of students than either the traditional or USM reimbursement models. Widespread adoption of either USM or CEP would “cost” the city budget the lunch fees collected from students who today pay the “full price” and until recently paid the reduced-price fee. IBO estimates that keeping participation constant, if CEP had been in place for all elementary schools (except for those already participating in the USM program) in school year 2014-2015 it would have increased the city’s net cost for school lunches by $5.2 million, while making free lunch available to almost 38,500 additional elementary school students. Increasing the participation rate would result in a larger increase in the net cost.

Although the CEP has only been available since 2012, sustainability of the program in its current form is already threatened due to federal legislation proposed last fall that would change funding from the appropriations format to a block grant. Under the Trump Administration, the future shape of a program like CEP becomes more uncertain.

A block grant would provide a set amount of funding to a state or district that may or may not be sufficient to cover actual programmatic costs. If funding does not keep pace with growth in costs and local demand, school districts would be faced with the choice of contributing additional funding from other sources or reducing the scale of their programs.

Another change would have raised the qualifying threshold for the count of vulnerable students from the current 40 percent to 60 percent of the student population. If this were to go into effect, based on current counts of automatically qualified students, New York City schools would no longer be eligible to participate in the CEP program. Currently, legislation with this amendment has already been approved by the House Committee on Education and the Workforce.

Prepared by Yolanda Smith

PDF version available here.

Endnotes

1Revolution at the Table: The Transformation of the American Diet, Harvey Levenstein [Oxford University Press: New York] 1988 (p. 116)297 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement, Jane Ziegelman [Smithsonian Books/Harper Collins: New York] 2010 (p. 165)

3Ibid.

4The linkage to using food surpluses and supporting demand for farm products is indicated by the administration of the NSLP under the Department of Agriculture, since 1946.

5Congressional Research Service, School Meals Programs and Other USDA Child Nutrition Programs: A Primer, Randy Alison Aussenberg, May 8, 2015, p.6

6DOE schools qualify for reimbursement under rates that reflect the fact that 60 percent or more lunches served during the second preceding school year were free or reduced price and the receipt of an additional 6 cents per lunch because the city meets new nutritional guidelines under the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act.

7The USM program includes school breakfast, which is why it is referred to as a meals program rather than just a lunch program.

8Based on DOE Title I allocations for 2016-2017.

92015 is the most recently available count of cash-assisted students from the Department of Education.

10School food and labor costs only included expenses that could be attributed to the lunch program and excluded expenses for breakfast, summer meals, and after-school meals. We were also unable to allocate utility and other fixed facilities costs to school kitchens and lunch rooms.

11In 2014-2015, the fees were $0.25 for reduced-price and $1.50 for full-price students. Beginning with the 2015-2016 school year, the DOE no longer collects a fee for reduced-price meals and the full-price fee was raised to $1.75. IBO estimated 249,481 elementary students in non-USM elementary schools in 2014-2015 (there were no CEP schools that year) to which we applied a 57 percent school lunch participation rate. According to the State Education Department’s Child Nutrition Management System data, 21 percent of students paid the full $1.50 lunch price and 6 percent paid the $0.25 reduced-lunch price.

Receive notification of free reports by e-mail