April 2013

Financing Redevelopment on the Far West Side:

City’s Spending on Hudson Yards Project Has Exceeded Initial Estimates

PDF version available here.

Summary

In 2005, the city launched its planned transformation of the Far West Side of Manhattan—an area that has become known as Hudson Yards—into a high-density office, commercial, and residential area through rezoning, the extension of the 7 subway line, and the creation of a new park-lined boulevard. To fund the infrastructure upgrades, the plan called for value capture financing, a strategy that uses the expected taxes and fees from new developments in the area to back the bonds issued to pay for the infrastructure improvements. Recognizing that in the early years of the project revenues would not be sufficient to make interest payments on the bonds issued to fund the redevelopment, the city committed to make up the difference.

The Bloomberg Administration is now proposing a major rezoning of East Midtown. Concerned that this new initiative would compete with Hudson Yards and slow the revenue growth needed to make Hudson Yards self-supporting, Council Member Daniel Garodnick asked IBO to review city spending to date on the plan and to consider the short-term outlook for revenues at Hudson Yards. Among our findings:

-

Public expenditures paid to the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation, including funds to help make interest payments on the $3 billion in bonds issued by the corporation, have totaled $374 million since 2006.

-

Over the same period, the city has committed an additional $22 million from its capital budget and $12 million from its operating budget to the project.

-

Revenue collected by the Hudson Yards corporation has fallen short of expectations. The corporation projected that it would collect $283 million in tax and fee revenues through 2012, but in fact has collected $170 million.

-

Property tax revenue that has been dedicated to the project (tax equivalency payments) from other newly developed buildings in the area is expected to grow from $28 million in 2012 to $33 million this year and $44 million next year. IBO expects payments from the first new office tower in Hudson Yards to begin in 2017 or 2018.

The extension of the 7 train, originally estimated at $2.1 billion, is now expected to cost $2.4 billion. The higher cost comes despite the complete elimination of one of the planned subway stations as well as savings on other parts of the subway-related work. The city is responsible for cost overruns on the 7 extension and $55 million of its $101 million in capital spending for Hudson Yards is for the transit work.

Background

In January 2005, the City Council approved a plan to transform the industrial blocks and rail yards of the Far West Side into a high-density, mixed-use neighborhood. The Far West Side was rezoned to accommodate 25 million square feet of office space, tens of thousands of residential units, new hotel and retail properties, and acres of new open space. (Initial proposals also called for a new stadium for the New York Jets football team that would double as an extension of the neighboring Javits Center, though those plans were later abandoned.)

As part of its vision, the city proposed $3 billion in new infrastructure projects to make this new development feasible. The lynchpin was the extension of the 7 train from its terminus in Times Square to a new station at 11th Avenue and West 34th Street. The city would also build a park-lined boulevard from West 30th Street to 42nd Street between 10th and 11th Avenues.

Despite the Bloomberg Administration’s advocacy for the subway project, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) had not prioritized the extension of the 7 train in its capital planning prior to the rezoning. Rather than let the infrastructure projects fail due to lack of financing by the MTA, the Bloomberg Administration made an unusual, if not unprecedented, proposal: the city would pay for nearly 100 percent of the subway improvements and other investments necessary to catalyze development in the Far West Side. (Normally, improvements to the transit system are funded by MTA capital proceeds and federal transportation grants. Given the priority of other projects like the Second Avenue Subway and East Side Access, it could have been years before the MTA committed to funding the 7 train extension.)

The financing plan that the Bloomberg Administration pursued is one of the few examples of a value capture financing strategy ever employed in New York City. (For background on the plan, see IBO’s West Side Financing’s Complex, $1.3 Billion Story") The theory behind the plan is that the rezoning of the Far West Side and the extension of the 7 subway line would vastly increase the development potential of land within the neighborhood. Rather than finance the project through its capital budget, the city could instead capture the tax and fee revenue generated by the new developments induced by the infrastructure investments and issue bonds backed by that revenue. The potential increase in value was substantial. According to the November 2006 revenue forecast prepared by Cushman & Wakefield for the city, new developments were expected to generate $283 million in revenue through 2012 and more than $34 billion by 2050.1 (Unless otherwise noted, all years refer to city fiscal years.)

The Bloomberg Administration and the City Council created two new local development corporations to implement this plan. The Hudson Yards Development Corporation (HYDC) is charged with managing the planning, design, and development of the Hudson Yards area, with the exception of the extension of the number 7 train, which is overseen by the MTA. The Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation (HYIC) is authorized to issue bonds to finance capital improvements in the Hudson Yards area. HYIC’s bonds are backed by revenue generated by new development projects in the Hudson Yards financing area (generally the blocks of West 30th to West 42nd Streets between 8th Avenue and the West Side Highway). The corporation has had two bond offerings to date: $2 billion in 2007 and an additional $1 billion in 2012. (HYIC can issue an additional $500 million worth of bonds with approval from the City Council.)

Given the expected lag between the start of infrastructure construction and the completion of the first new buildings, the City Council also agreed to make interest support payments to the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation should its revenues fall short of its annual debt service payments. Over time, as new buildings are completed, the Bloomberg Administration expects that the corporation will be able to pay 100 percent of the debt service on its bonds using project revenue. Once HYIC begins generating surpluses, it will begin to buy back bonds and to set aside money to pay principal that is scheduled to come due when its bonds mature.2

Revenue collected to date, however, has fallen short of the corporation’s initial forecasts. Through the end of 2012, HYIC has collected $170 million in tax and fee revenue, compared with the $283 million projected by Cushman & Wakefield. In addition, the corporation realized $252 million in interest earnings on its unused bond proceeds. HYIC’s interest expenses over the same period totaled $478 million.

Since 2006, public financial support for HYIC has totaled $374 million, including both foregone tax revenue otherwise due to the city’s general fund and direct appropriations from the city’s budget to make up the difference between HYIC’s revenue and its interest obligations. During that time, the city has provided $137 million in subsidies for so-called interest support payments to HYIC, with annual payments rising to more than $79 million in 2012. The city prepaid all of its 2013 and part of its anticipated 2014 interest support payments to HYIC from its 2012 budget surplus.3 In addition, the city has funded $22 million in capital improvements to date from its capital budget and spent $12 million from the expense budget on demolition of buildings in the area.

|

Public Expenditures Received by Hudson Yards

Infrastructure Corporation

Dollars in millions |

|||||||||||

|

Revenue Source |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

Total for

2006-2012 |

Total Paid

Through 2012 |

|

Interest Support

Payments |

$0.0 |

$0.0 |

$0.0 |

$0.0 |

$15.0 |

$42.7 |

$79.3 |

$125.0 |

$30.6 |

$137.0 |

$292.6 |

|

Tax Equivalency

Payments |

0.0 |

5.0 |

1.7 |

7.8 |

13.3 |

25.9 |

27.7 |

|

|

81.5 |

81.5 |

|

Total |

$0.0 |

$5.0 |

$1.7 |

$7.8 |

$28.3 |

$68.6 |

$107.0 |

$125.0 |

$30.6 |

$218.5 |

$374.1 |

|

SOURCES: Hudson

Yards Infrastructure Corporation Financial Statements,

fiscal years 2006-2012; Mayor’s Office of Management and

Budget

NOTES: Reflects

payments made by the city through June 30, 2012.

Interest support payments of $15 million for 2010 were

prepaid in 2009. Similarly, interest support payments

totaling $155.6 million for 2013 and 2014 were prepaid

in 2012. Totals may not sum due to rounding.

New York City

Independent Budget Office |

|||||||||||

Given that recurring payments in lieu of taxes (PILOT) revenue from office properties is unlikely to start until 2017 at the very earliest, and tax equivalency payments (TEP) from residential and hotel properties will increase slowly over the next few years, IBO expects the city will continue to make annual interest support payments to cover any shortfall at HYIC for the near future. Moreover, the city plans to commit an additional $79 million in city capital dollars through 2022.

This report updates IBO’s previous analyses of the Hudson Yards financing plan to reflect new developments over the last eight years. The brief is divided into three sections. The first provides an overview of what the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation and the city have spent on the Hudson Yards project to date. Next, we summarize the financing plan that backs the corporation’s bonds, as well as the subsidies the City Council has appropriated to date. Finally, we provide a short-term forecast for the corporation’s recurring revenues.

Hudson Yards Spending To Date

Through the end of 2012, the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation has spent nearly $2.0 billion on project-related expenses, which include the costs to acquire land and to design and build its capital projects. Most of that total ($1.58 billion) has been spent on the extension of the 7 train. HYIC has spent another $390 million on what it classifies as Land Acquisition and Public Amenities. The remainder has gone towards funding the Hudson Yards Development Corporation’s design and construction management work. Non-project expenses, which include interest payments, financing costs, and HYIC’s administrative expenses, have totaled $528 million.4 HYIC also used $200 million in bond proceeds to acquire transferrable development rights from the MTA, with the intention of reselling them to developers. Though not technically an expense, the acquisition reduced the funds available for capital projects.

|

Expenses of the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation |

||||||||

|

|

Expenses |

|||||||

|

|

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2006-2012 |

|

Project Expenses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Subway Extension |

$0.0 |

$37.6 |

$248.8 |

$391.9 |

$310.3 |

$275.6 |

$316.4 |

$1,580.6 |

|

Land Acquisition and Public Amenities |

0.0

|

71.0

|

264.5

|

(43.9) |

9.7

|

69.2

|

19.1

|

389.6

|

|

Transfers to HYDC |

1.5

|

6.2

|

3.0

|

5.2

|

4.3

|

3.2

|

3.0

|

26.4

|

|

Subtotal Project Expenses |

$1.5 |

$114.7 |

$516.2 |

$353.3 |

$324.3 |

$348.0 |

$338.6 |

$1,996.6 |

|

Non-Project Expenses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bond Interest |

$0.0 |

$0.0 |

$106.3 |

$90.1 |

$88.6 |

$88.2 |

$105.1 |

$478.4 |

|

General and Administrative |

0.4

|

0.4

|

0.6

|

0.6

|

0.7

|

0.8

|

9.5

|

13.1

|

|

Cost of Bond Issuance |

0.0

|

29.9

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

7.1

|

37.0

|

|

Subtotal Non-Project Expenses |

$0.4 |

$30.3 |

$106.9 |

$90.8 |

$89.3 |

$89.1 |

$121.6 |

$528.4 |

|

Total Expenditures |

$1.9 |

$145.0 |

$623.2 |

$444.0 |

$413.6 |

$437.1 |

$460.2 |

$2,525.0 |

|

Other Financing Uses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Payments to MTA for Eastern Rail Yards Development Rights |

$0.0

|

$100.0

|

$33.3

|

$33.3

|

$33.3

|

$0.0

|

$0.0

|

$200.0

|

|

SOURCE:

Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation Financial

Statements, fiscal years 2006-2012

New York City Independent Budget Office |

||||||||

Subway Extension.

The budget for the design and construction of 7 train extension is currently $2.42 billion, of which $2.37 billion will be funded by HYIC’s bond proceeds. HYIC has spent $1.58 billion on the subway extension through the end of 2012. Service is expected to begin in June 2014.When the project was first announced in 2006, the city and MTA budgeted $2.1 billion for the extension, including a 5 percent contingency allowance to cover potential cost overruns. In September 2008, bids to excavate the first phase of the extension came in higher than expected. In order to save $450 million and keep the project on budget, the city chose not to fund the construction of a shell for a second station at 41st Street and 10th Avenue.

By 2011, despite the earlier round of cuts, the total budget had risen to more than $2.4 billion, including the contingency allowance. Since the city was responsible for funding these overruns, HYIC and the Mayor’s Office chose to finance the $267 million shortfall through a combination of cutbacks and additional city capital spending.5 The city identified $235 million in savings by tapping into a portion of the project’s contingency fund and taking advantage of savings found in other aspects of the project, including lower than expected costs for both land acquisition and HYDC’s operating expenses. The remaining $32 million in overruns is being funded through the city’s capital budget. (Actual and planned city capital spending on the 7 train extension currently stands at $55 million. See page 5 for more information.)

According to the transportation authority, HYIC has spent $1.58 billion on the subway extension through 2012. The majority of that, $1.3 billion, has been for construction and construction management, with an additional $107 million spent on design. Another $149 million were spent on design, construction, and management work not related to the subway. This category includes construction work related to public amenities that had to be coordinated with the work on the subway, though was not directly related to subway operations. The MTA also funded $53 million for work related to the Environmental Impact Statement.

If the project stays on budget, the remaining construction work will cost up to $786 million, which is expected to be paid from the remaining bond proceeds. Construction costs account for $565 million of the remaining budget, with an additional $117 million in nonsubway work that will be funded by HYDC. Construction management is expected to cost $21 million. The budget includes a $76 million reserve for subway expenses that may or may not be spent, depending on final project costs.

If project costs exceed the budget, the city will either have to find savings elsewhere in the project, appropriate additional city capital money, or tap into HYIC’s remaining $500 million of bond capacity, which would require City Council approval. At the time this report was prepared, HYIC has no plans to issue additional debt.

|

7 Train Extension Budget and Expenditures Through June 2012

|

|||

|

|

Total Budget |

Expenditures |

Budget Remaining |

|

Final

Design |

$114.0 |

$107.3 |

$6.7 |

|

Construction |

1,870.9 |

1,305.8 |

565.1 |

|

Construction Management |

40.0 |

19.3 |

20.7 |

|

Subway

Project Reserve |

75.9 |

0.0 |

75.9 |

|

Total HYDC-Funded Subway Work |

$2,100.8 |

$1,432.4 |

$668.4 |

|

HYDC-Funded Nonsubway Work |

266.0 |

148.9 |

117.1 |

|

Total of HYDC-Funded Subway and Nonsubway Work |

$2,366.8 |

$1,581.3 |

$785.5 |

|

MTA-Funded Environmental Impact Statement Work and Other |

53.1 |

53.0 |

0.1 |

|

TOTAL |

$2,419.9 |

$1,634.3 |

$785.6 |

|

SOURCE:

Metropolitan Transportation Authority Transit Committee

Report, July 2012

New York City Independent Budget Office |

|||

Land Acquisition and Public Amenities. Through 2012, HYIC reports that it has spent $390 million to acquire land and to design and build the project’s public spaces. This figure does not include the $200 million that HYIC paid to the MTA to acquire a 50 percent interest in over 4 million square feet of transferrable development rights (TDRs), also known as air rights, from the MTA’s Eastern Rail Yard. HYIC records the TDRs as an asset because they are intended to be resold to developers at a later date. As such, the $200 million payment to the MTA is not classified as an expense, even though the funds came out of HYIC’s bond proceeds. Until the TDRs begin to be sold, however, this represents a reduction in the total funds available for capital projects.

Of the $390 million in spending on land acquisition and public amenities, $378 million represents money paid to property owners to acquire the land necessary to complete the project. According to the city, HYIC has no plans to acquire additional property for the Hudson Yards project. The full list of properties acquired, either in full or in part, was not made available to IBO at this time, though public documents state that HYIC and the MTA have condemned property necessary to build the subway extension and the first phase of public open space improvements in the Hudson Yards area.6

The remaining $12 million was spent on the public amenities. This lines up with what is reported in the city’s capital plan, with $10 million in private funds (from HYIC) committed through 2012 for city capital projects related to the reconstruction of West 33rd Street and the park and boulevard, discussed below in more detail.

The city is also spending $12 million to demolish buildings in the Hudson Yards area. The demolitions are funded through the Department of Housing Preservation and Development’s expense budget.

Culture Shed. The city has also proposed a 170,000 square foot multipurpose arts facility on the site of the Eastern Rail Yards. The building, known as the Culture Shed, will be administered by Culture Shed, Inc., a nonprofit organization whose board is appointed by the Mayor.7 The city plans to acquire the land under the proposed Culture Shed and lease it to Culture Shed, Inc. to build and operate the facility. HYDC has also received a $100,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts to help fund the project’s design.

As of this report, the city has not announced how much the project will cost or the share of costs that the city will bear. One media report suggested that the project will be funded by a combination of city funds and private donations.8 It is expected to open in 2017.

City Capital Projects in Hudson Yards. The city’s current capital plan includes a number of projects directly related to the development of Hudson Yards, including parts of the 7 train extension, street and open space improvements, and water and sewer connections. The city is expected to fund $101 million, or 46 percent, of this additional work, with the remainder coming from HYIC bond proceeds.

The city’s capital plan calls for $88 million in work relating to the extension of the 7 line. Through 2012, $51 million has been spent on the project, with 60 percent of the funding, or $30 million, coming from HYIC’s bond proceeds. The remaining $37 million in work to be completed will be funded almost entirely from the city’s capital budget, with only $2 million to be funded from HYIC’s bond proceeds.

The reconstruction of West 33rd Street and the construction of the first phase of the midblock park and boulevard between 10th and 11th Avenue are primarily funded using proceeds from the Hudson Yards bonds. Construction on these projects is expected to continue through 2014 at a total cost of $86 million, with nearly all of it ($85 million) paid for with bond proceeds. Through 2012, preliminary work on these two projects has cost $12 million, of which $10 million came from bond proceeds and the remaining $2 million from city funds.

The first phase of the midblock boulevard and park covers only the blocks between West 33rd Street and West 36th Street. HYIC does not plan to acquire land or fund the construction of the second phase of the park, which includes the blocks between West 36th Street and West 39th Street. Instead, it anticipates that developers of properties along those blocks will build Phase 2 of the boulevard and park in exchange for additional development rights.

|

Actual and Planned Capital Spending in Hudson Yards Area

|

|||||||||

|

|

Actual (2005-2012) |

Planned (2013-2022) |

Total |

||||||

|

Project |

City |

HYIC |

Total |

City |

HYIC |

Total |

City |

HYIC |

Total |

|

Number

7 Train Extension |

$20.4 |

$30.2 |

$50.6 |

$35.0 |

$2.0 |

$37.0 |

$55.4 |

$32.2 |

$87.6 |

|

Reconstruction of West 33rd Street |

$1.7 |

$2.8 |

$4.5 |

$0.0 |

$39.6 |

$39.6 |

$1.7 |

$42.4 |

$44.1 |

|

Midblock Boulevard and Cross Streets |

$0.0 |

$7.3 |

$7.3 |

$0.0 |

$34.9 |

$35.0 |

$0.0 |

$42.3 |

$42.3 |

|

Reconstruction of Water and Sewers |

$0.0 |

$0.0 |

$0.0 |

$44.3 |

$0.0 |

$44.3 |

$44.3 |

$0.0 |

$44.3 |

|

Total |

$22.0 |

$40.3 |

$62.4 |

$79.3 |

$76.5 |

$155.9 |

$101.4 |

$116.9 |

$218.3 |

|

SOURCES: Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget; New

York City Financial Management System

New York City Independent Budget Office |

|||||||||

The city also plans to fund another $44 million in water and sewer improvements in Hudson Yards from its capital budget. This project is not funded from HYIC’s bond proceeds and no funds had been committed as of the end of 2012.

The city is also conducting routine street reconstruction, bridge maintenance, and other water and sewer work throughout the Hudson Yards project area. IBO has not included spending on those projects, under the assumption that most of these projects would have likely taken place even if the Hudson Yards rezoning had not passed.

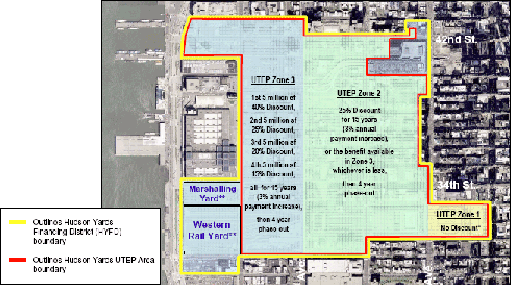

Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation Revenue to Date

When it created the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation, the city pledged that it would redirect all tax and fee revenue generated by new projects in the Hudson Yards area to repay the $3 billion in bonds issued by the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation. The borders of the Hudson Yards Financing District are shown in the map below. Though the project was initially centered on the MTA’s Eastern Rail Yards, the financing area covers dozens of blocks in the West 30s and 40s. The irregularly shaped area also extends east to include Madison Square Garden and Penn Plaza, north to include portions of the blocks between 42nd and 43rd Streets, and south to 29th Street between 11th and 12th Avenues. It includes the Port Authority Bus Terminal, but carves out the Javits Convention Center and the piers along the Hudson River.

SOURCE: Hudson Yards Development Corporation

Currently, the corporation receives two different types of revenue. The first type, called project revenue, is revenue generated directly by new development projects in the Hudson Yards financing area, while the second type, called non-project revenue, is revenue that does not stem from new development.

HYIC receives two different kinds of project revenue: development rights that the city sells to developers at the time of construction and recurring, annual property tax revenue (or the equivalent) paid by owners of new buildings in the Hudson Yards area, including payments in lieu of taxes revenue collected by the Industrial Development Agency (IDA) and tax equivalency payments (TEP) appropriated to HYIC by the City Council.

HYIC’s non-project revenue represents the revenue it receives from sources other than the taxes and fees paid by new development projects. To date, HYIC has received two kinds of non-project revenue: the earnings it collects from investments of its unused bond proceeds and interest support payments (sometimes paid in advance as grants) from the city, which the City Council appropriates each year if HYIC’s other sources of revenue fall short of its annual debt service payments.

Recurring Property Tax Revenue. As part of its agreement with the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation, the city has pledged to transfer to HYIC all property tax revenue paid by buildings in the Hudson Yards area that have been newly constructed or substantially renovated after January 19, 2005, as evidenced by the issuance of a temporary or final certificate of occupancy. Due to legal restrictions, however, the city created two different mechanisms to accomplish this. Certain commercial properties can apply to the city’s Industrial Development Agency to receive full exemptions on their property tax obligations in exchange for payments in lieu of property taxes. These agreements are referred to as PILOTs. All other new or renovated properties that do not enter into PILOT agreements with the IDA pay their property taxes normally. For these remaining properties, the City Council has agreed to appropriate an amount of money equal to the total real property taxes they pay each year. This transfer to HYIC from the general fund is referred to as a tax equivalency payment, or TEP.

Payments in Lieu of Real Property Tax. Based on its initial market studies, the city determined that the construction of office space on the Far West Side would not be economically feasible without some level of public subsidy. To ensure that projects in Hudson Yards would be competitive with projects in more desirable locations, office projects in the Hudson Yards area are eligible to receive a full exemption on their real property tax obligations for up to 19 years in exchange for agreeing to make PILOT payments to the IDA. The PILOT payments are structured to offer property owners discounts of up to 40 percent relative to what they would have paid if they were not exempt. Developers can also receive full exemptions on sales taxes on construction materials.

To qualify, projects must meet certain requirements. First, they must be located within specific areas of the Hudson Yards project area known as the Uniform Tax Exemption Policy area, which largely overlaps with the Hudson Yards Financing District, with the exception of the Western Rail Yard, the Javits Center’s marshalling yard, and the Port Authority Bus Terminal. Projects must be at least 1 million square feet in size, with at least 75 percent of the usable space dedicated to Class A office space or other commercial uses. Buildings must also be built to at least 90 percent of the maximum square footage allowed under the zoning code, including all bonuses.

There has been no revenue paid though PILOT agreements as of the end of June 2012 because there has been no new office construction meeting PILOT requirements in the Hudson Yards area. The Related Companies’ (Related) first office tower in the Eastern Rail Yards, popularly known as the south tower with Coach, Inc. as its anchor tenant, is expected to enter into the first PILOT agreement with the IDA. With construction beginning in winter 2013 (this could ultimately be reflected on the 2014 or 2015 property tax assessment roll) and the building receiving the standard three-year construction period, the south tower is not likely to begin paying a PILOT until 2017 or 2018.9

The PILOT payments made by buildings will flow directly from the Industrial Development Agency to the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation, which means that they will not appear in the city’s budget.

Tax Equivalency Payments. Other than buildings that enter PILOT agreements with the Industrial Development Agency, buildings in the Hudson Yards financing area pay their real property taxes normally, as they would if they were located anywhere in New York City. Each year, the Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget identifies all buildings that have been built or substantially renovated since January 2005 and sums all of their tax payments for the fiscal year, including adjustments made in the current year for taxes paid in previous years.10 A building’s property taxes can start counting toward the tax equivalency payment on the tax roll immediately following the issuance of a temporary or final certificate of occupancy by the Department of Buildings. As part of the budget process, the Bloomberg Administration requests that the City Council appropriate the sum of these payments to the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation in the form of a tax equivalency payment.

|

Tax Equivalency Payments By Property Type |

||||||

|

|

Tax Equivalency Payments |

|||||

|

|

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

Total |

|

Hotel |

$0.1 |

$0.5 |

6.0 |

$11.2 |

$11.8 |

$29.6 |

|

Rental |

4.3 |

4.1 |

5.8 |

6.1 |

8.2 |

28.6 |

|

Condo |

0.1 |

0.2 |

1.9 |

4.6 |

5.0 |

11.8 |

|

Commercial |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.2 |

2.4 |

2.9 |

8.5 |

|

Total |

$5.5 |

$5.9 |

$15.0 |

$24.2 |

$27.9 |

$78.5 |

|

SOURCES: Department of Finance, Mayor’s Office of

Management and Budget

New York City Independent Budget Office |

||||||

The market for residential and hotel development in the Hudson Yards area has proven to be strong, even during the 2008-2009 recession. IBO reviewed 36 residential, hotel, and commercial properties that contributed to the tax equivalency payments made from 2008 through 2012. These properties include buildings that have been built or renovated in the financing area since 2005, including at least four parcels that were substantially completed prior to the rezoning but had not yet received a final Certificate of Occupancy at the time the rezoning was adopted.11 These figures do not match the TEP payments in the city budget. While the amounts for 2009 through 2012 are close, there is a more substantial discrepancy in 2008, with the budget figures about $3 million higher than our analysis of the property tax data suggested. However, IBO needed to estimate 2008 TEP payments for six properties because of missing data, possibly contributing to the discrepancy. Since the city has not provided building-level details on payments made prior to 2012, it is not possible to reconcile the difference.

Based on tax data available for individual parcels, IBO estimated the tax equivalency payments from 2008 through 2012 total $78.5 million. This cumulative estimate from individual tax lots is about $3 million lower than the aggregate reported in the city’s Financial Management System. Taxes paid by hotels in the Hudson Yards financing district have provided $29.6 million to HYIC since 2008, while rental buildings added another $28.6 million in property tax revenue. Condominiums have seen a smaller tax contribution, totaling $11.8 million from 2008 through 2012. Commercial property that did not qualify for a PILOT through the Industrial Development Agency, either due to building size or use, has contributed $8.5 million to the tax equivalency payments.

Upfront Fees and Bonus Payments.

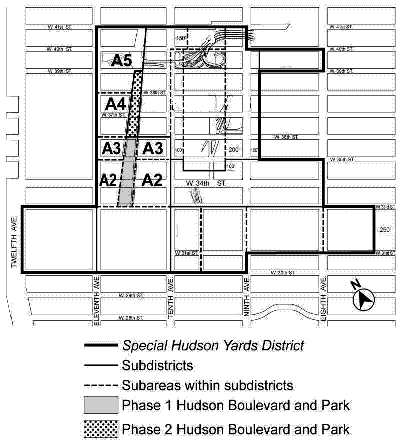

The rezoning of the Hudson Yards neighborhood dramatically increased the amount of space that developers can build within the district. Rather than simply increasing the amount that developers could build as-of-right, however, the city created what is essentially a layer cake of development rights, in which developers pay bonuses or purchase transferrable development rights from other sites in order to assemble the maximum development potential of their properties.The exact composition of this layer cake of development rights differs for commercial and residential properties. For all buildings, the first layer is based on the floor-area ratio that developers can build as-of-right under the zoning code. (Floor-area ratio, or FAR, is the ratio of a building’s square footage to the square footage of the lot on which it is built. For example, on a 2,000 square foot lot with a FAR of 5.0, a developer could build a 10,000 square foot building.)

|

Layered Development Rights by Property Type |

||

|

|

Commercial |

Residential |

|

Layer 3 |

Transferrable Development Rights from Eastern Rail Yards

(where available) |

District Improvement Fund Bonus |

|

Layer 2 |

District Improvement Fund Bonus, or

Phase 2 In-Lieu Contribution |

District Improvement Fund Bonus and Inclusionary Housing

Bonus, or Phase 2 In-Lieu Contribution and Inclusionary

Housing Bonus |

|

Layer 1 |

As-of-Right |

As-of-Right |

|

SOURCE: New York City Zoning Resolution, Article IX, Chapter 3:

Special Hudson Yards District

New

York City Independent Budget Office |

||

For commercial buildings, the second layer is added by paying a district improvement fund bonus (DIB) for each incremental square foot developed up to a specific FAR threshold. Depending on a building’s location, developers can acquire additional density on top of the district improvement fund bonus by purchasing transferrable development rights from the Eastern Rail Yard.

For developers of residential buildings, the second tier of development rights comes from the purchase of DIBs and the use of inclusionary housing bonuses. Developers must add six square feet of inclusionary housing for every five square feet of FAR increase added through DIBs, up to a specific threshold. Developers can fulfill their inclusionary housing obligations either by providing affordable units on-site or by paying for the construction of affordable housing elsewhere in the neighborhood. Once a building has reached this threshold, developers can add additional FAR by paying for additional district improvement fund bonuses.

Developers of residential and commercial properties located adjacent to the second phase of the Hudson Boulevard and Park are also eligible to add FAR to their sites in exchange for building a portion of the boulevard or park. Developers can substitute development rights from these Phase 2 in-lieu contributions for development rights that they would otherwise have to purchase from the District Improvement Fund.

District Improvement Fund Bonus. The Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation has collected more than $88 million in revenue from the sale of District Improvement Fund Bonuses through 2012, though collections have slowed dramatically since 2008. DIB payments are made when developers apply for a building permit and payments flow directly to HYIC. In January 2005, the Department of City Planning set the initial price at $100 for every square foot of development rights acquired through the program. The city planning department updates the price each August based on the percentage change in the consumer price index for the previous 12 months. As of August 2012, the price of DIBs had increased to $120.61 per square foot.

Developers can elect to build a portion of the Phase 2 section of boulevard and park in exchange for additional development rights. These air-right bonuses come in two forms. First, developers can acquire a lot designated as a Phase 2 site and transfer its development rights to a nearby lot along the boulevard that they intend to develop. In addition, they can also apply to the City Planning Commission to receive a second floor-area bonus in exchange for building the public park land. Since these contributions can be substituted for rights that developers would otherwise purchase from the District Improvement Fund, the Phase 2 financing plan could reduce DIB revenue flowing to HYIC. No developments have used the Phase 2 bonus or transferrable development rights to date.

As part of its December 2006 agreement with HYIC, the city agreed to assign all DIB revenue paid by Hudson Yards projects to HYIC. This means that DIB revenue does not appear in the city budget.

Eastern Rail Yards Transferrable Development Rights. The Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation purchased a 50 percent interest in 4.56 million square feet of transferrable development rights from the MTA’s Eastern Rail Yards for $200 million using proceeds from its 2007 bond offering. Under the terms of the agreement between HYIC and the MTA, the Hudson Yards Development Corporation has the authority to market and sell the development rights to developers of new commercial buildings along the proposed boulevard between 10th and 11th Avenues north of West 33rd Street, which is the northern boundary of the Eastern Rail Yards. According to the zoning resolution, the rights cannot be sold within the Eastern or Western Rail Yards or to developers building on the Amtrak rail yards located between the Eastern Rail Yard and the Farley Post Office. (The zoning resolution restricts the sale of the Eastern Rail Yard TDRs to property owners located in zoning subareas A2, A3, A4 and A5.) Since these TDRs are part of the third layer of benefits, developers must maximize development capacity added from the second layer of development rights before they can purchase additional development rights from the Eastern Rail Yard.

SOURCE: NYC Zoning Resolution Article IX, Chapter 3, Special Hudson Yards District, Appendix A

The price of the transferrable development rights will be set at the lesser of the price of the district improvement fund bonus at the time of the sale or 60 percent of the per square foot value of the development that is receiving the bonus as determined by an independent appraiser.

The terms of the agreement also set out how HYIC and the MTA split the proceeds. HYIC will receive all of the proceeds from the sale of the development rights until it has collected $200 million, plus the interest it has paid on the $200 million up to that point. 12,13 After that milestone is reached, the MTA will receive all of the proceeds earned on the remaining sales.

Through the end of the 2012, the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation has not sold any of the 4.56 million square feet of development rights. No commercial construction has begun in the areas eligible to receive the air rights, and no projects in that area have announced plans to begin construction in the near future.

Payments in Lieu of Mortgage Recording Taxes. Commercial projects that enter into PILOT agreements with the Industrial Development Agency also are required to make payments in lieu of the mortgage recording tax. These payments flow to the IDA, which will then convey them to HYIC. To date, no projects have made payments in lieu of mortgage recording tax, though Related’s south tower is expected to make one in 2013 once its construction loan closes.

Payments in Lieu of Sales Taxes. Projects that enter into PILOT agreements with the IDA can also apply for exemptions on the sales tax due on construction materials. The Uniform Tax Exemption Policy grants the Industrial Development Agency wide latitude in granting sales tax benefits. The IDA can offer savings ranging from 100 percent of sales and use taxes to no benefit at all. Projects that receive partial exemptions or no benefits would be required to make a payment in lieu of sales taxes equivalent to what they otherwise would have owed. As with payments in lieu of the mortgage recording tax, these payments flow to the IDA, then to HYIC.

To date, Related has not applied for a sales tax exemption for the south tower. It is unclear if the company will apply for an exemption at a later date.

Interest Earnings on Bond Proceeds.

The Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation has earned more than $250 million from investing its unused bond proceeds. These earnings helped cover its structural deficits during the first years of its existence, but the earnings have fallen over time. By 2012, revenue from investment earnings had fallen to $1.4 million. (Some portion of the earnings are available to pay debt service, though the city has not said how much of these funds were available and used each year to help HYIC make its interest payments.)Through the end of 2011, HYIC’s investment earnings came almost entirely from a series of flexible repurchase agreements it entered into after the sale of its first bonds in 2007. Under the terms of the agreements, the city invested its unspent bond proceeds in investment vehicles that paid fixed rates of return ranging from 4.635 percent to 4.835 percent and that allowed it to withdraw money as needed to pay for capital expenses. The agreements expired in March 2011.

As of June 30, 2012, HYIC had nearly $938 million in investments, including the unspent proceeds from its 2012 bond offering. These proceeds are now invested in a combination of high-grade commercial paper, Treasury bills and money market funds, and notes from the Federal Farm Credit Bank and Fannie Mae. Given that the yields on these investments are substantially lower than what the city earned on its now-expired repurchase agreements, it is unlikely that HYIC will be able to use investment earnings to significantly reduce the city’s interest support obligations in the future.

Interest Support Payments and Grants.

The final source of revenue backing the HYIC bonds is interest support payments from the city’s debt service budget. The City Council is not legally obligated to support HYIC, but it has agreed to subsidize the corporation should its revenue fall short of its annual debt service payments on up to $3 billion worth of bonds. This support comes in the form of interest support payments, which are appropriations from the city’s budget for interest due on HYIC’s outstanding debt in the current fiscal year.In some years, the Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget opts to prepay interest support payment from the budget surplus available at the end of the year. Using the budget surplus to prepay debt service expenses is a common practice. Because the city must end the year with a balanced budget with revenues equaling expenses, the city uses any available surplus to prepay certain expenses that would otherwise be due in the following year. The most common items to prepay are debt service expenses and subsidy payments to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority or the city’s libraries. HYIC shows the prepayment as a grant from the city in the year the payment is made, even if it is intended to cover interest payments in a later year.

The city’s first payment came at the end of 2009, when it made a $15 million prepayment (or grant) to HYIC out of its surplus in that year, which was used to cover HYIC’s interest payment shortfall in 2010. In 2011 and 2012, the city appropriated the interest support payment during the year it was due, making a payment of $43 million in 2011 and $79 million in 2012. The city has also made a prepayment of $156 million from the 2012 surplus. According to city budget documents, the $156 million is expected to cover the entire interest support payment for 2013 and part of the interest support payment for 2014.

Summarizing Revenue Through 2012.

Project revenue has fallen short of the corporation’s annual debt service payments. Through the end of 2012, HYIC collected $170 million in project revenue (revenue from development), while interest payments over the same period totaled $478 million. The city did not expect the project to be self-sustaining in its early years, even in a best case scenario. But the $170 million in project revenue through 2012 fell well short of HYIC’s initial forecast of $283 million.|

Hudson Yards Infrastrucure Corporation Revenue Before

Interest Support Payments

|

||||||||

|

|

Revenue |

|||||||

|

|

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2006-2012 |

|

Recurring Revenue Sources |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Payments in Lieu of Taxes

|

$0.0 |

$0.0 |

$0.0 |

$0.0 |

$0.0 |

$0.0 |

$0.0 |

$0.0 |

|

Tax Equivalency Payments |

0.0

|

5.0

|

1.7

|

7.8

|

13.3

|

25.9

|

27.7

|

81.5

|

|

One-Time Revenue Sources |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eastern Rail Yards Transferrable Development Rights |

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

|

Payments in Lieu of Mortgage Recording Tax |

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

|

Payments in Lieu of Sales Taxes |

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

0.0

|

|

District Improvement Bonus |

11.1

|

57.9

|

6.9

|

4.5

|

0.0

|

4.6

|

3.0

|

88.1

|

|

Total

Revenue from Development |

$11.1 |

$62.9 |

$8.6 |

$12.3 |

$13.3 |

$30.6 |

$30.6 |

$169.5 |

|

Investment Earnings on Bond Proceeds |

$0.1 |

$43.3 |

$127.3 |

$57.6 |

$20.0 |

$2.6 |

$1.4 |

$252.2 |

|

Total Revenue Before Interest Support Payments |

$11.2 |

$106.2 |

$135.9 |

$70.0 |

$33.3 |

$33.2 |

$32.0 |

$421.7 |

|

SOURCE: Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation Financial

Statements, fiscal years 2006-2012

New

York City Independent Budget Office |

||||||||

Through 2010, HYIC subsidized its operations and obligations primarily using the money it earned by investing the bond proceeds it had yet to spend. However, total earnings fell as the corporation began spending money on projects, interest rates fell, and the composition of its portfolio changed, declining from a peak of $127 million in 2008 to $1.4 million in 2012. As a result, the corporation has had to rely increasingly on interest support payments from the city’s debt service budget to close the gap between its revenue and its annual debt service obligations.

According to Cushman & Wakefield’s November 2006 forecast, interest support payments through 2012 were expected to be between $7 million and $228 million, depending on the amount of projected development that took place. In its conservative cyclical forecast, Cushman & Wakefield estimated that the city would need to make $205 million in payments through 2014, with $119 million coming through 2012. A more conservative estimate at 60 percent of the cyclical scenario projected interest support payments of $804 million through 2023, with $228 million through 2012. In its baseline forecast, Cushman & Wakefield predicted that the city would make only a single $7 million payment in 2008. While the city’s actual payments are in that range, development has been far slower than projected and the city has not had to compensate with higher interest support payments because of HYIC’s significant investment earnings, which were not included in the 2006 forecast.

Cushman & Wakefield updated its interest support payment forecast in 2011, when it estimated that the city would be required to make $295 million in interest support payments for 2012 through 2018, beyond payments that had already been made by the city totaling $58 million.

|

Revenue and Interest Expenses of the Hudson Yards Infrastructure

Corporation |

||||||||

|

|

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2006-2012 |

|

Total

Revenue Before Interest Support Payments |

$11.2

|

$106.2

|

$135.9

|

$70.0

|

$33.3

|

$33.2

|

$32.0

|

$421.7

|

|

Interest Expenses |

0.0

|

0.0

|

106.3

|

90.1

|

88.6

|

88.2

|

105.1

|

478.4

|

|

Surplus/(Deficit) |

$11.2

|

$106.2

|

$29.6

|

($20.2) |

($55.3) |

($55.0) |

($73.1) |

($56.6) |

|

Interest Support Payments |

$0.0 |

$0.0 |

$0.0 |

$0.0 |

$15.0 |

$42.7 |

$79.3 |

$137.0 |

|

SOURCE:

Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation Financial

Statements, fiscal years 2006-2012

New York City Independent Budget Office |

||||||||

Revenue Forecast

Using property tax data on buildings completed to date and building permit data on projects likely to be completed in the near future, IBO created a forecast of HYIC’s revenue from PILOT and tax equivalency payments in 2013 and 2014. The forecast focuses on the recurring revenue sources for two reasons. First, payments from upfront development fees, bonuses, and the sale of transferrable development rights are difficult to forecast because they are not paid until a developer files for a building permit. Second, the refinancing covenants in the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation’s bonds are based on the recurring revenue sources, which the bond market considers to be a better indicator of the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation’s fiscal self-sufficiency.

PILOT Revenue.

Even though the Related Companies began construction on its first office tower in the Eastern Rail Yard during 2013, that building is not likely to begin generating PILOT revenue for HYIC until 2017 or 2018. Related will also not pay any upfront fees other than its payment in lieu of the mortgage recording tax (expected in 2013, once the loan closes). Based on the zoning of the Eastern Rail Yard, Related does not have the option to purchase additional development rights from the DIB fund. Additionally, due to its location in the Eastern Rail Yard, Related cannot purchase any of the rail yard’s transferrable development rights.At the time of this report, no other properties have applied to the Industrial Development Agency to enter into a PILOT agreement.

Developers have assembled a number of commercial development sites in the Hudson Yards area. If these buildings are constructed, the developers will ultimately pay PILOTs, though probably not until 2019 at the earliest. At least six sites comprising 11.4 million square feet of development rights are actively competing for tenants:

-

Coach, Inc. plans to occupy 740,000 square feet of The Related Companies’ 1.7 million square foot south tower, which is currently under construction. L’Oreal is leasing 402,000 square feet and SAP, a German technology company, is leasing 115,000 square feet.Related has yet to secure tenants for the remaining portion of the building.

-

Related also continues to seek tenants for its 2.5 million square foot north tower in the Eastern Rail Yard.

-

Brookfield Office Properties controls development rights on the Amtrak rail yards located between the MTA yards and Farley Post Office (covering the blocks from 8th Avenue to 9th Avenue). It has announced plans for two office towers totaling 3.2 million square feet and a platform over the yards.

-

The Moinian Group is expected to break ground in 2014 on a 1.7 million square foot building on the west side of Hudson Boulevard between 34th and 35th Streets that could contain offices or a mixture of offices and residential or hotel development.

-

Extell Development Company has released designs for a 1.3 million square foot office building along the west side of the Hudson Boulevard between 33rd and 34th Streets.

-

Alloy Development has proposed a 1.1 million square foot building on the east side of the boulevard between 35th and 36th Streets.

With the exception of Related’s south tower, none of these projects have announced that they have signed tenants or secured financing. If all of these buildings were completed and all the square footage was dedicated to office space (rather than residential, retail, or hotel), office development would total 11.4 million square feet. This would represent 45 percent of the 25.3 million square feet that Hudson Yards was rezoned to accommodate.

Tax Equivalency Payments.

In addition to the 36 buildings already being counted for TEPs, four other new properties are scheduled to have their property taxes count as tax equivalency payments beginning in 2013. Included are two hotels and two residential buildings: the OutNYC/Axel on West 42nd Street, the TRYP by Wyndham on West 35th Street, a rental at 446 West 38th Street and a condominium at 433 West 37th Street. The estimated 2013 TEP for the four buildings is $1.2 million, with 88 percent coming from the two hotels. The remaining 36 properties that currently have their property tax revenue transferred to HYIC in the form of TEPs are estimated to have combined tax payments (including payments for prior years made in 2013) of $32 million in 2013. With the four new projects, the total TEP in 2013 is estimated to be $33 million.Based on the tentative tax roll for 2014, these 40 properties are scheduled to see their taxes rise to $44 million in 2014. Their final property tax liabilities for 2014 will likely be slightly lower than that amount due to routine exemption processing, corrections, and reductions by the Tax Commission. Abatements and additional tax reductions via the Tax Commission may also reduce the property tax liability beyond the final tax roll.

Based on a review of new building permits issued between 2009 and 2012 and press accounts, IBO has identified 7 additional buildings that are currently under construction and will likely begin contributing TEP revenue in the near future, possibly 2014 or 2015, depending on when they receive a temporary certificate of occupancy. Because the timing of the temporary certificate of occupancy is uncertain, we did not include these buildings in the TEP projection at this time. The buildings are: two hotels on West 37th Street, one hotel on West 33rd, and four new buildings expected to be residential developments, including the 750,000 square foot residential tower being developed by the Extell Development Company on 41st Street and 10th Avenue. Additionally, the first building at the Brookfield Office Properties’ Amtrak Yards site is now expected to be a residential tower that would ultimately qualify for a TEP; however, completion is likely to be later than 2015.

|

Projected Tax Equivalency Payments By Property Type |

||

|

|

Projected TEP Payments |

|

|

|

2013 |

2014 |

|

Hotel |

$14.3 |

$23.0 |

|

Rental |

$8.3 |

$9.8 |

|

Condo

(inc. 1-Family) |

$8.3 |

$8.7 |

|

Commercial |

$2.2 |

$2.3 |

|

Total |

$33.2 |

$43.6 |

|

SOURCES: Department of Finance, Mayor’s Office of

Management and Budget

New

York City Independent Budget Office |

||

Looking Ahead

Through 2012, the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation (HYIC) spent almost $2 billion on the 7 subway extension, land acquisition, and public amenities in the Hudson Yards area. Additionally, HYIC spent about $480 million on debt service for $3 billion dollars worth of bonds. Completion of the subway expansion is expected to cost up to an additional $786 million, while the city’s capital plan includes another $77 million from HYIC for the public amenities. The city has committed $22 million in city funds for capital projects related to Hudson Yards and plans to commit another $79 million through 2022.

HYIC revenues for 2006 through 2012 have included $252 million in investment earnings, $137 million in interest support payments from the city, $88 million in district improvement bonuses, and $82 million in tax equivalency payments. Additionally, the city paid $156 million in interest support payments in 2012 that are intended for 2013 and part of 2014. Transfers from the city budget to HYIC total $374 million, including the interest support payments and tax equivalency payments.

IBO expects that additional interest support payments from the city will be required to cover annual HYIC shortfalls. One-time revenue, from the sale of development rights or district improvement bonuses, is particularly difficult to forecast because of the uncertain timing of major development projects. Given projected construction dates for office buildings in Hudson Yards, IBO expects recurring PILOT revenue will begin in 2017 or 2018 for the Related south tower and may increase beginning in 2019, if other office buildings under development begin construction in the near future. IBO forecasts that tax equivalency payments will increase to $33 million this year and $44 million in 2014.

Report prepared by Sean Campion

Endnotes

1

These figures are in nominal dollars.2

HYIC’s bond indenture dictates how the corporation can spend surplus revenue, how and when it can begin redeeming bonds, and the conditions it must meet before it can pay down principal. HYIC cannot redeem or purchase its bonds for approximately 10 years following the issuance of each of its bond offerings: February 15, 2017 for the 2007 bonds and February 15, 2021 for the 2012 bonds. After those dates, HYIC can use surplus funds to buy back bonds from bond holders at a price of 100 percent of principal, plus accrued interest.Once HYIC meets certain revenue thresholds, it is required to establish a sinking fund, into which HYIC will set aside funds to pay off the principal that comes due when its bonds mature. As described in the bond indenture, the requirements are that HYIC’s recurring revenue must meet or exceed 125 percent of debt service on its senior bonds for two consecutive fiscal years and its revenue in the current fiscal year must exceed the maximum debt service in all remaining years of the bond offering.

3

In the December 2006 Hudson Yards Support and Development Agreement, the city agreed to appropriate in the Mayor’s expense budget the difference between the interest due on HYIC’s outstanding debt in the upcoming fiscal year and the amount of money that HYIC reasonably expects to be available for debt service payments in that year. That total is adjusted over the course of the fiscal year as revenue comes in.4

We are reporting both project expenditures from the $3 billion in bonds and debt service for those bonds in the same table, consistent with HYIC financial statements, even though that may lead to some double-counting.5

In September 2006, the city, HYDC, HYIC, and the MTA entered into a memorandum of understanding (MOU) for the extension of the 7 train that spelled out each party’s responsibilities. The MOU listed the scenarios, referred to as Hudson Yards Modifications, in which the city, HYDC and HYIC would be responsible for paying for cost overruns. These scenarios include instances in which the city: fails to complete its project commitments; modifies the scope or design of the project for a number of reasons, including compliance with applicable laws and real estate development issues; forces delays in the project; or adds one or more supplemental items, including a station entrance from the midblock boulevard and park, a station shell at West 41st Street and 10th Avenue, or a station entrance from West 35th Street.6

The Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget declined to provide IBO with a list of parcels that were acquired at this time because there are on-going negotiations regarding prices. Once all transactions are finalized, the Mayor’s budget office indicated that the list would be available.7

See http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323296504578396863718422762.html8

See http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/16/realestate/commercial/developers-prepare-to-compete-for-tenants-in-hudson-yards.html?pagewanted=all9

The building permit was issued on November 27, 2012 and construction began in December 2012. However, the construction is not reflected on the tentative 2014 roll, which means that the first year of construction could be either 2014 or 2015. The nature of the tax lot further complicates the timing. While there is a commercial tax lot that is associated with the permit, it has no market value attributed to it. The market value is currently attributed to a Real Estate of Utility Companies (REUC) tax lot; unlike all other tax lots which are assessed by the city (tentative roll in January and final roll in May), REUC tax lots are assessed by New York State in April. Additionally, the city replaced the existing tax lots with new lots in February 2013 and assessment information will not be available until the final roll is released in May. It is not clear how the city will structure the tax lot and valuation to reflect the construction, though we expect the building to ultimately be shown as a number of condominium tax lots.10

The Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget reviews the buildings’ accounts for any payments or credits to taxes paid in prior years in the current fiscal year, such as a retroactive Tax Commission reduction in tax liability. This review is completed twice a year. The current year adjustments to prior years’ taxes are combined with payments made during the current year for the current year liability to determine the TEP.11

The four parcels are 315 West 33rd Street (block=757 and lot=37), 400 West 37th Street (block=734 and lot=22), 430 West 33rd Street (block=729 and lot=163), and 609 West 29th Street (block=675 and lot=24). The lots recieved temporary certificates of occupancy in 2003 or 2004 that have been renewed on a regular basis. As of March 2013, three of the four lots have still have not recieved their final certificates of occupancy.12

According to the agreement, HYDC is charged with marketing and selling the development rights, while HYIC receives the revenue until HYIC recoups the cost of the purchase, plus interest.13

The annual interest due on a $200 million bond issued at a 5 percent interest rate is $10 million, paid in two installments of $5 million each. HYIC’s 2007 bond offering was issued mid way through that fiscal year, which means that HYIC made one interest payment in 2007 and two payments in each year since. Assuming the $200 million in bonds were sold on these terms, HYIC will have paid $55 million in interest by the end of 2012. This means that the threshold for the MTA to begin receiving proceeds has risen to $255 million and will increase by an additional $5 million every six months.

PDF version available here.