February 2017

Detailing the Expansion of Behavioral Health Services:

City-Funded Spending Drives New & Growing Programs Under the Mayor’s ThriveNYC Initiative

PDF version available here.

Summary

Unlike other signature de Blasio Administration initiatives such as universal pre-kindergarten, Housing New York, and Vision Zero, relatively little attention has been focused on ThriveNYC. Launched in November 2015, ThriveNYC is a multipronged effort to expand the availability and public awareness of behavioral health services in the city. The plan also aims to reduce the stigma often associated with seeking help for mental health issues.

In this fiscal brief, IBO details the increase in public resources being committed to the 54 initiatives under the umbrella of ThriveNYC. Some of these initiatives are new, others expansions of existing programs. Among our findings:

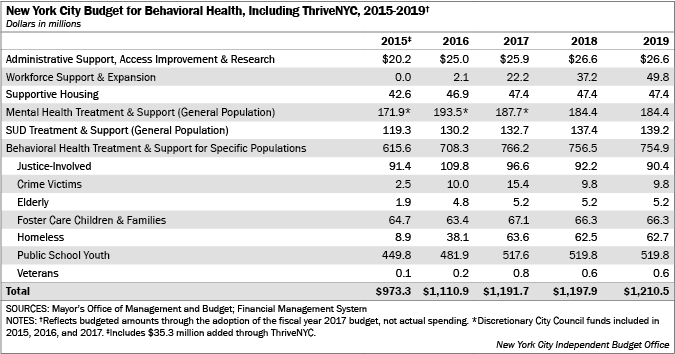

- With ThriveNYC underway, the city’s budget for behavioral health care is projected to grow by 25 percent, from $973 million in 2015 to $1.2 billion in 2019.

Over the years 2016 through 2019, the budget for ThriveNYC programs is expected to total $816 million, growing from $129.7 million in 2016 to $232.6 million in 2019. - Prior to the ThriveNYC plan, about three-quarters of the funding for behavioral health services in the city came from state and federal aid. In contrast, the Mayor expects city dollars to fund 78 percent of ThriveNYC initiatives over the 2016-2019 period.

- A number of programs aimed at assisting specific populations would grow considerably under ThriveNYC. Among the behavioral health services that are expected to grow the most in budget terms are services for the homeless in shelters and on the streets, support for health clinicians in high-needs areas of the city, and mental health programs in public schools.

The success of ThriveNYC requires substantial coordination among city agencies and programs and the buy-in of the existing network of behavioral health care providers. But the biggest hurdle could be funding. Given the uncertain fiscal landscape confronting the city, whether the de Blasio Administration can commit the expected level of city funds to the new and expanded services under ThriveNYC remains to be seen.

In November 2015 the de Blasio Administration published a plan—”ThriveNYC”—to increase access to behavioral health care services in New York City by adding a total of $816 million of planned spending over four years.1Prior to this plan the city had budgeted $938 million towards behavioral health in 2015.2ThriveNYC will increase the city’s annual spending on behavioral health to $1.2 billion by 2019. The ThriveNYC plan increases funding for the direct provision of behavioral health services in schools and other city agencies, and adds new funding for citywide planning and initiatives that improve access to services. One important result of the ThriveNYC plan is that a greater share of funding for behavioral health care will come directly from the city itself. State and federal sources funded about three-quarters of the city’s behavioral health budget in 2015 before the ThriveNYC plan was released; in contrast, the city is budgeted to fund 78 percent of the ThriveNYC initiatives from 2016 through 2019.3

In order to put these shifts into fiscal context, IBO reviewed the city’s behavioral health budget for 2015, before the implementation of ThriveNYC. The bulk of this annual budget supported behavioral health services in public schools ($450 million) and contracts with nonprofit organizations that provide behavioral health services ($376 million). IBO also analyzed the $855 million in contracts and grants that city, state, and federal government agencies had in place with behavioral health care providers in 2015.

This report begins by defining the behavioral health care system and describing the history of its government funding. Subsequent sections detail the state of government support for behavioral health care providers in 2015 and then describe the impending shifts under ThriveNYC and funding for behavioral health services in 2016 through 2019.

BackgroundBehavioral Health Care System. In 2014 over 43 million adults in the U.S. (18 percent) experienced mental illness. Of this population, almost 10 million experienced a serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Over 20 million U.S. adults (8.5 percent) experienced a substance use disorder (SUD).4 Each year in New York City over 1.3 million adults experience some form of mental illness and hundreds of thousands more are expected to experience a substance use disorder. Both mental illness and SUD are more common among adults in poverty and those without health insurance than those with higher incomes and health insurance.5

The behavioral health care system consists of a range of treatment and support services provided in a variety of settings for people with mental illness and substance use disorders. (This report focuses only on government spending on support for people with mental health and substance use conditions and does not include public expenditures for people with developmental disabilities.) A patient’s age, coexisting medical conditions, personal history, family/community support, insurance status, income, mobility, available means of transportation, and incarceration status can all affect their ability to receive behavioral health care and the type of care they receive. Organizations that provide behavioral health care include clinics, residential facilities, religious institutions, hospitals, schools, advocacy groups, and other community-based organizations. Many of these organizations offer multiple services. A community center may offer psychotherapy sessions, group support, and vocational training; a hospital may have an inpatient ward, an outpatient clinic, and mobile treatment teams; and a supportive housing program can offer treatment, rehabilitative, and support services for their residents as well as nonresidents.

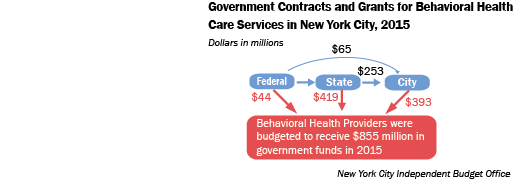

Government agencies on the federal, state, and local level fund organizations that provide treatment, support, and housing to people with behavioral health conditions. In 2015—before the NYCThrive program took effect— the city funded $376 million in contracts to provide behavioral health care, while state and federal agencies funded an additional $463 million in contracts and grants to support the behavioral health care system. This public funding allows organizations to provide both services for vulnerable populations and services that receive little or no reimbursement from health insurance.

The ThriveNYC budget includes funding for workforce training and technical support to organizations that serve people with behavioral health conditions, as well as a cadre of new behavioral health clinicians to work in these organizations. These efforts, along with other program expansions, will result in more city behavioral health service contracts.

Access and Barriers to Behavioral Health Care. Left untreated, serious mental illness and substance use disorders can result in medical complications, hospitalization, loss of housing, and other crises. People may not receive treatment because they do not want or believe they need treatment, but also because of substantial barriers to accessing care for those who want treatment.6 People with mental illness or substance use disorders who also have low incomes or are uninsured are less likely to receive treatment than those with higher incomes and health insurance.7 Nationally, 74 percent of insured adults with a serious mental illness report receiving treatment, compared with only 51 percent of adults who are uninsured.8 In New York City, just 61 percent of adults with a serious mental illness reported receiving treatment in 2014.9 Individuals with substance use disorders are even less likely to be in treatment.

Prior to ThriveNYC, the city funded initiatives to increase access to health care services overall, but did not invest substantially in programs aimed specifically to address barriers to behavioral health care. Just as with barriers to accessing medical care, barriers to accessing behavioral health care can be structural, financial, and cultural; some barriers, though, are unique to behavioral health services.

Structural barriers include the lack of accessible behavioral health professionals and services in New York City, especially in some less dense and lower-income areas of the city, and the lack of knowledge of treatment options among both patients and medical professionals. Cultural barriers include the stigma of mental illness and substance use disorders, which may cause some patients not to seek care or to not use their health insurance to pay for care.10

While costs can be a barrier to accessing any health care services, financial barriers to behavioral health services are particularly steep because of the potential need for ongoing services, medication, and support. Financial barriers include high costs, limitations on health insurance coverage and reimbursement, and a lack of health insurance for some individuals. In New York State a combination of federal and state laws require almost all health insurance plans to cover some level of mental health care; however, cost sharing policies and limits on the types, frequency and duration of services covered can make behavioral health care prohibitively expensive.11 In addition, finding a provider that accepts health insurance as a form of payment can be difficult. A national survey of physicians found that only 55 percent of psychiatrists accepted private insurance and 43 percent accepted Medicaid.12 Providers are presumably responding to the complex logistics of reimbursement, low payments, and limits on services by health insurance plans. Those that do not accept insurance payments charge patients directly for services, which are prohibitively costly for many New Yorkers. Medicaid beneficiaries (nearly a quarter of New York City adults and half of children) and those without health insurance (14 percent of New York City adults) have particular difficulty finding treatment and support services they can afford.13 As noted above, even those patients with private health insurance who locate a provider that accepts their insurance may still have high co-payments or limits on the number of appointments covered.

ThriveNYC is designed to address barriers to behavioral health care through media campaigns to promote awareness of behavioral health services and reduce stigma, programs to help New Yorkers find services, and training for providers. In addition, ThriveNYC includes programs to expand the amount of behavioral health services in areas of high need and for specific populations including the homeless, those involved with the criminal justice system, and public school students. The success of ThriveNYC is highly dependent on the ability of these strategies to connect New Yorkers with behavioral health care.

| How Government Began Funding Behavioral Health Care

Over the last five decades, government agencies have evolved to support two major aspects of the behavioral health care system: community mental health care and supportive housing. These programs trace back to the deinstitutionalization of the mentally ill during the 1960s and 1970s and the accompanying community mental health treatment movement. Community Mental Health Care. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, changing medical and cultural standards, the advent of psychiatric medications, and the patients’ rights movement drove the process of the deinstitutionalization of the mentally ill in the United States. States closed and downsized many of their large residential psychiatric institutions as they released many existing patients and took in fewer new ones. The establishment of the Medicaid and Medicare programs (1965) provided further incentive for the mentally ill to be treated in the community, as these programs originally did not pay for any services provided by state-run “institutions for mental disease.” The population of New York State’s psychiatric institutions dropped from a peak of over 90,000 in 1955 to about 13,000 in 1992.14 The federal government attempted to spur the creation of a national network of community-based mental health centers by giving states funds to support community health centers. Another funding source for community mental health care was state funds freed-up from closing psychiatric institutions.15 These funds, however, were insufficient and the national network of “therapeutic centers” to replace “custodial mental institutions” never fully emerged.16 By the 1980s the federal government provided states with block grants to fund mental health and substance use disorder treatment and the states passed some of this funding on to localities.17 Today federal, state, and city government agencies continue to fund many organizations that provide outpatient behavioral health services in New York City. Medicaid and Medicare also now provide some funding for inpatient psychiatric facilities, although this is still limited. New York State continues to operate 25 psychiatric facilities, 8 of which are located in New York City.18 Supportive Housing. In the 1970s, deinstitutionalization, other policy shifts, and rising real estate prices spurred the need to provide individuals who are mentally ill with housing and basic living assistance. Many of the patients released from psychiatric institutions lacked the resources or skills to secure housing and were homeless or precariously housed upon release. Beginning in the 1970s nonprofit organizations developed housing programs—now known as supportive housing—for the homeless mentally ill. Many of these programs were initially located in single room occupancy buildings and were funded by a patchwork of city, state, and federal grants. In 1990 New York City and New York State launched a formal funding program to build and sustain housing for the homeless mentally ill with housing and basic living assistance. Many of the patients released from psychiatric institutions lacked the resources or skills to secure housing and were homeless or precariously housed upon release. Beginning in the 1970s nonprofit organizations developed housing programs—now known as supportive housing—for the homeless mentally ill. Many of these programs were initially located in single room occupancy buildings and were funded by a patchwork of city, state, and federal grants. In 1990 New York City and New York State launched a formal funding program to build and sustain housing for the homeless mentally ill, called the New York/New York Residential Placement Management System, colloquially known as the NY/NY Agreements.19 The city and state expanded the NY/NY Agreements in 1999 and 2005 to provide housing for individuals and families led by people with mental illness, substance use disorders, HIV/AIDS, and other chronic medical conditions. The programs are run under contracts with nonprofit organizations and offer varying treatment and support services in addition to housing. If tenants have an income they pay a fixed percentage of that income towards rent. City and state agencies fund capital expenditures to build supportive housing units and operating expenditures to maintain these programs. Many behavioral health organizations run supportive housing programs in addition to providing outpatient treatment and support services. Although the city and state have historically struggled to find enough organizations to build and operate these programs, as of 2014 the NY/NY Agreements had made available 14,000 new units of supportive housing. (For more on the history of the NY/NY Agreements see IBO publications from 2002 and 2010.) |

The Behavioral Health Budget Prior to ThriveNYC

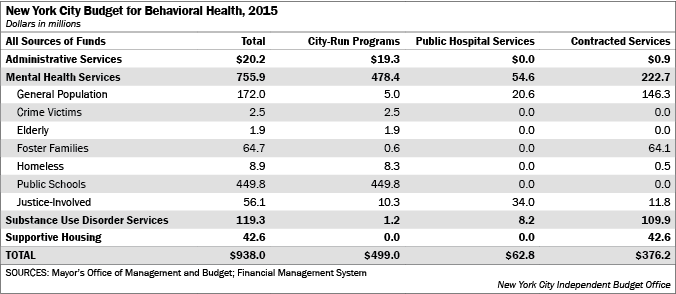

IBO examined the city’s behavioral health budget for 2015, the last year before the implementation of ThriveNYC initiatives.20 The money flowing through the city’s budget for behavioral health includes funds from all levels of government: city, state, and federal. In 2015 the city funded the provision of behavioral health treatment and support services by health care professionals and nonprofit organizations (contracted services); acted as a provider of behavioral health care for some specific populations (city-run programs); and funded behavioral health care at the public hospital system. The chart below displays the total of $938 million the city budgeted for 2015, divided into those funds for: city-run programs ($499 million, 53 percent), the public hospital system ($63 million, 7 percent), and contracted services ($376 million, 40 percent) along with the target populations of those programs.

While most of the 2015 funding for contracted services and the public hospital system supported mental health and substance use disorder services for the general population, almost all of the funding for programs run by the city itself supported services available to specific populations. Over 90 percent of the $499 million budgeted for city-run behavioral health care programs was used to support the 2,800 social workers, guidance counselors, and mental health workers based in public schools. This funding also paid for city employees who are behavioral health providers working with individuals involved in the justice system, residents of homeless shelters, crime victims and the elderly, as well as administrative staff to manage contracts and other programs.

In 2015 the city budgeted $63 million for its public hospital system, NYC Health + Hospitals (H+H), to provide behavioral health care within specific city agencies and to provide some services to the general population. A little over half of this funding—$34 million—supported services provided by H+H within the city’s jails as well as services provided to other justice-involved populations. The remaining funds supported clinical treatment, crisis intervention, SUD treatment, mobile treatment teams, and other programs for the general population at H+H facilities. H+H reported that their hospitals and clinics provided a total of $1 billion in mental health care in 2015.

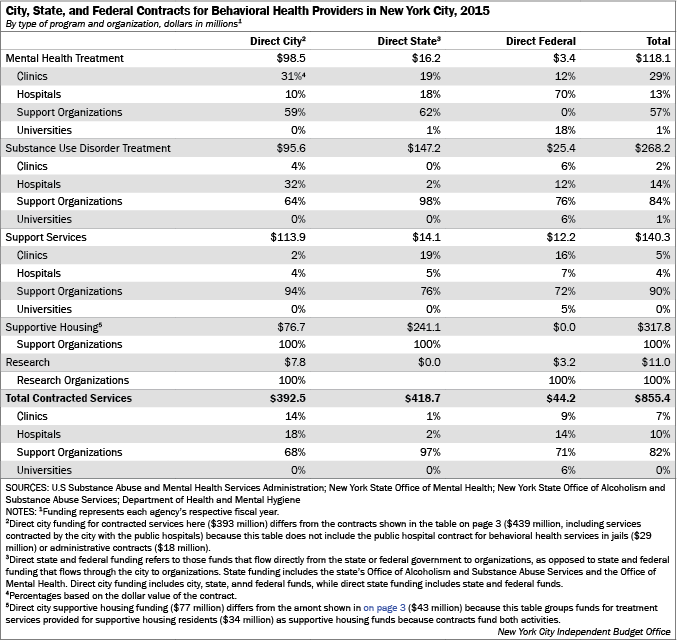

Lastly, the city’s 2015 behavioral health budget included $393 million to fund contracts with behavioral health providers to offer city residents various services. Most of these contracts also funded services for the general population, rather than for a population served by a specific agency. The largest share of the city’s contracts to provide behavioral health care funded community-based organizations that offer a wide variety of services, rather than hospitals or clinics (see chart below). The Department of Health & Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) held the majority of these city contracts (budgeted at $245 million in 2015); DOHMH contracts funded mental health and SUD treatment programs, rehabilitation programs, crisis services, syringe exchange programs, and housing programs. DOHMH employed about 170 behavioral health providers and 215 administrative staff to oversee its programs and contracts in 2015. The Human Resources Administration (HRA) funded contracts to support the rehabilitation and vocational training of people with SUD who receive public benefits ($69 million), the Administration for Children’s Services (ACS) funded contracts to support parents with SUD and the mental health needs of children ($64 million), and the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice funded contracts with organizations that operate alternative to incarceration programs for people with mental illness and SUD ($2 million). The following section provides greater detail on these city contracts, as well as the contracts city hospitals, clinics and other nonprofit organizations also received from state and federal agencies.

Government Contracts for Behavioral Health Services. City, state, and federal agencies managed $855 million in contracts with behavioral health providers in 2015, $393 million of which were managed by the city.21 ThriveNYC does not explicitly increase the value of these existing city contracts; some ThriveNYC programs will be administered through new contracts.

IBO has sorted the government-funded behavioral health service contracts and grants with New York City organizations by level of government providing the funds, programs funded, and organizations funded. Mental health treatment funds included agreements to provide specific programs for specific populations as well as more generalized funding. Support services include outreach and advocacy programs, employment assistance and care management services for people with mental illness and/or SUD. Funding for supportive housing included only operating (not capital) funds for organizations that provided subsidized housing for individuals and families led by people with mental illness or SUD.

City: The city’s $393 million in contracts funded the provision of mental health treatment ($98 million), supportive housing operations ($77 million), SUD treatment ($96 million), and support services ($114 million). The city received $253 million from the state and $65 million from the federal government in 2015 to support these contracts, while city dollars funded the remaining $75 million. The majority (68 percent) of the city’s behavioral health care contracts funded support organizations, although a third of SUD treatment contracts funded hospitals. Contracts averaged less than $1 million a year. The highest average contract was for SUD treatment ($1.4 million) and $34 million of these contracts funded programs at NYC Health + Hospitals.

DOHMH budgeted $257 million in funding to 144 organizations to provide behavioral health services in 2015.22 Most of DOHMH’s contracts for the provision of mental health treatment allowed the organization funded to determine the particular programs or populations the funding supports. However, $20 million in contracts funded services targeted to specific populations, including people involved with the criminal justice system ($7.3 million), the homeless ($5.1 million), seniors ($4.2 million), and the seriously mentally ill ($3.4 million). In addition, $18 million funded specific programs, including crisis intervention ($4.9 million), advocacy programs ($4.2 million), and Assertive Community Treatment programs ($3.4 million). DOHMH’s contracts to provide SUD prevention and treatment ($48 million) specified target populations and the specific type of program, such as methadone or opioid treatment programs, outpatient clinic, or crisis programs. In addition to DOHMH’s contracts, ACS provided $64 million in funding for organizations providing behavioral health care to children and families involved with the foster care system and HRA provided $69 million in funding for organizations providing treatment and support services to people with substance use disorders.

State: In addition to the $253 million that the state provided to fund city-administered contracts, the New York State Office of Mental Health (OMH) and Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services (OASAS) collectively provided $419 million in contract and grant funding to 176 New York City organizations to provide behavioral health services in 2015. In turn, a portion of the state’s direct contracts with behavioral health organizations and the state’s support for city contracts were funded by federal grants. OMH and OASAS contracted with organizations that provide treatment, support services, and supportive housing for people with mental illness and SUD, respectively, and offered a limited number of specialized grants; total grant funding far exceeded total agency contracts. The largest share of direct state funding was used to finance supportive housing programs (58 percent) and treatment for substance abuse disorders (35 percent). The state provided relatively little direct funding for mental health treatment and support services, presumably because the state provides funding for the city’s mental health treatment contracts. Like the city, the majority of the state’s funding for mental health treatment, support services, and supportive housing went to support organizations. The state differed from the city in that nearly all (98 percent) of its direct funding for SUD treatment went to support organizations, rather than to hospitals.

Federal: In 2015 the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) provided $44 million in direct grants to 67 New York City organizations, along with $65 million to city government agencies and $210 million to New York State to fund behavioral health services. The state passed along a portion of its $210 million SAMHSA grant to the city to fund its direct behavioral health service contracts, but IBO was not able to determine how much was transferred.

Most of SAMHSA’s direct grants funded SUD treatment (58 percent) and support services (28 percent). SAMHSA grants are used to fund novel projects, rather than targeted at the community mental health or supportive housing initiatives described in the previous section. The 2015 SAMHSA grants funded traditional behavioral health organizations (such as hospitals, schools, and clinics) operating innovative programs that would not be funded by health insurance reimbursement, including primary care and behavioral health integration projects, SUD screening and treatment programs, and suicide prevention hotlines. SAMHSA grants also supported projects aimed at especially vulnerable populations such as individuals with HIV/AIDS, the recently incarcerated, and youth living in poverty. The rationale for state and federal support for outpatient SUD treatment programs is based on the limited health insurance reimbursement for these services and the vulnerability of targeted populations.

Overall, city, state, and federal government agencies provided $318 million for the operation of supportive housing programs in 2015, $118 million for mental health treatment, $268 million for substance use disorder treatment and $140 million for behavioral health support services. The majority of 2015 contracts (82 percent) funded nonmedical support organizations, including advocacy groups, housing developers, human service providers, and other community-based organizations.

| Changes in the State’s Medicaid Behavioral Health Funding

Organizations receiving government contracts often serve many Medicaid, Medicare, and uninsured patients. Over the last two decades the New York State Medicaid program has shifted the majority of its beneficiaries—over 84 percent in 2014—into managed care plans.23 Until very recently the state omitted most behavioral health services from managed care agreements and did not enroll beneficiaries with serious behavioral health conditions in managed care plans; instead these services were paid for on a fee-for-service basis. In October 2015 the state expanded behavioral health benefits for adult beneficiaries enrolled in Medicaid Managed Care plans in New York City and began enrolling beneficiaries with serious behavioral health conditions into specialized managed care plans (known as Health and Recovery Plans, or HARPs). In January 2016 Medicaid Managed Care started covering home and community-based services for adult beneficiaries enrolled in HARPs in the city; these services include rehabilitation, vocational, and crisis intervention services. The expansion of behavioral health services for children under Medicaid Managed Care plans is scheduled to begin in October 2017. Medicaid beneficiaries now need to ensure that their behavioral health care providers are included in their specific managed care plan’s network, and some receive coverage for more services. While behavioral health providers may be able to receive more Medicaid reimbursement (i.e. more services types are now covered and some services are paid at a higher rate), providers need to update their billing systems to receive Medicaid managed care reimbursement. The state created public online technical resources to support organizations during this transition, as well as specific grants for additional support. In March 2016 Governor Cuomo’s office announced $3.3 million in grants (averaging $44,000 per grant) to support information technology infrastructure operations for 76 community-based behavioral health and developmental disability service providers in the city; the grants were funded in the state’s 2016-2017 budget. Additional startup funds for children’s behavioral health providers have been planned, but not yet awarded. Throughout this transition, behavioral health organizations continue to receive funding from city, state, and federal agencies through contracts and grants in addition to reimbursement from insurance. Although some organizations have expressed concerns that increases in insurance reimbursement may lead to declines in state and city contracts to provide behavioral health services, the city is not currently assuming a decrease in state or federal funding of city contracts for behavioral health services. |

ThriveNYC

ThriveNYC is the city’s first comprehensive plan to address its residents’ behavioral health. The plan aims to increase access to behavioral health care in New York City with two main strategies: (1) increase the amount of behavioral health services available in the city; and (2) help people locate and use these services.24 The 54 initiatives outlined to execute these strategies include a mix of completely new programs and expansions to existing programs, some of which target specific populations such as public school students or children in foster care. Most of the initiatives designed to increase the use of behavioral health services will expand existing programs and most of the initiatives that aim to facilitate the use of services will be implemented through the creation of new programs.

Overall, ThriveNYC will increase the city’s budget for behavioral health services by 25 percent, from $969 million in 2015 to $1.2 billion in 2019; in contrast, the city’s behavioral health budget was relatively constant over the last decade.25 While the city will remain a source of funding for existing behavioral health care providers, ThriveNYC will change the city’s role in the behavioral health care system from that primarily of a funder to that of an active participant in creating programs and providing treatment. Many of the new city-run behavioral health programs will aim to reach all New Yorkers, rather than subpopulations, and will be supported by city funds. As noted previously, state, federal, and other sources funded about three-quarters of the city’s 2015 behavioral health budget before the implementation of ThriveNYC. The majority of the ThriveNYC budget is funded through city dollars (78 percent) with the rest of funding from state (9 percent) and federal (7 percent) sources, as well as asset forfeiture funds from the Manhattan District Attorney (5 percent).

The majority of the four-year $816 million ThriveNYC budget funds the expansion of existing programs (56 percent), and the remaining 44 percent funds programs that are new.26 Initiatives that target specific populations account for 80 percent of the plan’s budget. IBO has broken out the ThriveNYC budget by initiative (see chart here) and projected the city’s total behavioral health budget with the implementation of ThriveNYC. From a budgetary perspective, the largest of the initiatives are those that will: provide behavioral health services for the homeless in shelters and on the street (increasing to $53.4 million annually by 2019), fund additional behavioral health clinicians in high-need areas of the city (growing to $48.3 million annually), increase behavioral health services within public schools (reaching $41.4 million annually by 2019), and fund services and support for people involved with the criminal justice system ($42.6 million annually in 2019). The plan also includes policy-based initiatives that do not require funding and initiatives that will receive funding that does not flow through the city budget.

Impact on Existing Programs. ThriveNYC increases the city’s budget for behavioral health services in transitional shelters for the homeless, city courts and jails, and public schools as well as for seniors at senior centers and for foster care families. Notably, funding for behavioral health services in shelters is budgeted to increase from $8.9 million in 2015 to $62.7 million in 2019. In addition, ThriveNYC will revamp the city’s call center to help people find behavioral health services. City dollars support all of the increases in the budget for all services for seniors, three-quarters of the increase in services in public schools, and a third of the increase in services for the homeless.

While the majority the ThriveNYC budget expands funding for existing city behavioral health programs, it does not affect them all. The plan does not affect HRA’s provision of support and treatment to people with substance use disorders and does not increase the value of DOHMH’s contracts with organizations to provide mental health and SUD treatment. ThriveNYC includes $3 million annually for supportive housing programs for people with mental illness who are released from jail and a commitment to build 15,000 new units of supportive housing in the future. It does not alter the city’s support for the operation of existing supportive housing programs.

New Programs. ThriveNYC also includes several new initiatives that aim both to increase the use of behavioral health services in the city and help New Yorkers access those services. These programs are mostly supported by city dollars.

The largest new initiative to increase the use of behavioral health care in the city is the Mental Health Corps. At full implementation this program aims to enlist about 400 behavioral health clinicians who are early in their careers, to work in existing behavioral health organizations in high-need areas of the city, funded with $48.3 million annually. The Mental Health Corps is intended to not just add capacity, but introduce and advance new delivery models. The other new initiatives that will increase the amount of behavioral health care in New York City include training for people who have experienced behavioral health conditions in their own lives to become peer counselors and mental health first aid training for city employees and other New Yorkers, an early childhood health network to treat young children, and the Community Schools Initiative, among others.

Other new programs aim to expand New Yorkers’ ability to find and use behavioral health services. With the exception of an initiative to expand the capability of the city’s existing call center, none of these initiatives are based on preexisting programs. New initiatives include the use of media campaigns, citywide planning efforts, and the creation of a website to help community-based organizations support their clients with behavioral health conditions. In addition, ThriveNYC’s budget funds ongoing research and evaluations of its programs. While these programs (including the call center) account for a small portion of the budget for new ThriveNYC programs, they are crucial to its overall success. If patients do not know about the availability of services and cannot locate services when they need them, overall access will not increase. These support program initiatives aim to serve all New Yorkers and are funded almost completely with city dollars.

Some of the new ThriveNYC programs also aim to provide behavioral health services to specific populations. These include creating police drop-off centers to divert people with behavioral health conditions from jails, providing social emotional learning for children in ACS Early Learn programs and public pre-k settings, and hiring advocates for victims of crime and domestic violence to work in police precincts and social workers to staff centers for runaway youth. NYC Safe is also a new package of mental health service enhancements and new initiatives for people with mental illness who may also be homeless, have criminal justice involvement, and are in the shelter system. Through NYC Safe, people with mental illness and/or substance abuse disorder and a history of violence will receive enhanced attention towards meeting their needs. NYC Safe will also increase security in shelters. With the exception of some state funding for advocates for victims of domestic violence and youth in foster care, all the funding for new programs is supported by city dollars.

The new programs in ThriveNYC also include policy-based initiatives that do not require new funding, such as obtaining commitments from hospitals to screen for maternal depression. Other new ThriveNYC initiatives will rely on sources of funding other than the city budget. For example, the Connections to Care program will rely on federal and private grants to support behavioral health providers in organizations that have not previously offered these services. In March 2016 the Mayor’s Fund to Advance New York City awarded Connections to Care program grants to 15 social service organizations; the grants will allow the organizations to partner with mental health providers to train their staff and serve their clients.27

Implementation. ThriveNYC aims to increase access to behavioral health care for all New Yorkers. It will be important to track the implementation of the plan’s various initiatives—which include hiring, contracting, and acquiring rental space—along with rates of behavioral health care treatment. The City Council has proposed 11 specific metrics to track the implementation, although others could be developed.28 It will also be important to follow the extent to which the city builds on existing contracts with social service organizations to provide new behavioral health services and if it is able to leverage existing—mostly state and federally funded—contracts and grants to serve the goals of ThriveNYC.

The city’s financial role in the behavioral health care system has historically been dominated by supporting the city’s hospitals, clinics, and social service organizations and it is not certain how changes resulting from a broader city role under ThriveNYC will affect these entities. In addition, the January 2015 bankruptcy of one of the largest social service organizations in New York City, the Federation Employment and Guidance Services, has highlighted concerns over the challenges that nonprofit organizations face when contracting with the city for all types of services and it is possible that there will be changes in the contracting process independent of ThriveNYC.29 While social service organizations in the five boroughs will have ample opportunity for increased funding through Medicaid payment reform and ThriveNYC programs in the coming years, they may need to devote substantial resources to adapting to these changes.

From Ideas to ImplementationThriveNYC aims to improve the behavioral health of all New Yorkers through the implementation of a wide range of initiatives and programs. The success of ThriveNYC will require significant coordination between agencies and programs, and the buy-in of the existing behavioral health care delivery system. This is one reason for the creation of a cross agency mental health planning council. In the near term, ThriveNYC will increase the city’s funding for behavioral health providers and the amount of behavioral health services available to New Yorkers. Yet the future of this funding and the city’s relationship with existing behavioral health providers remains less certain.

ThriveNYC represents a commitment by the city to improve the behavioral health of its residents and will expand the city’s role in the behavioral health care system. The city will more actively administer behavioral health treatment and programs to increase access to behavioral health care as it continues to be a source of funding for the behavioral health care system.

Although the city has not substantially decreased its existing contracts with behavioral health providers, it could opt to draw down these funds to support its own programming in the future. For example, the Mental Health Corps initiative plans to fund the employment and placement of 400 behavioral health clinicians at clinics in high-need areas of the city, many of which will likely already receive some city funding under ThriveNYC. If the city continues to fund these positions ($48 million annually) with new city spending, the clinics will certainly benefit from the additional staff. If the city instead opts to fund these positions in future years using its existing budget for contracted services, organizations could see a reduction in their city funding. This would be particularly challenging for those organizations that do not receive behavioral health clinicians through the Mental Health Corps. The city has not indicated that it plans to fund its new programs by reducing funding for existing contracts, but such action could be taken as the city’s budget does not guarantee funding beyond this fiscal year.

New York City’s behavioral health care system is facing substantial change. In addition to the city’s new initiatives, other major changes in behavioral health care include increases in the types of services eligible for Medicaid reimbursement, shifts in the cost structure of Medicaid, and possible expansion of the New York/New York supportive housing program. As these initiatives are implemented in the coming years, this history of the relationship between government agencies and the behavioral health care system serves as a reference point.

Report prepared by Erin Kelly

PDF version available here.

Endnotes

1IBO’s four-year budget total of $816 million reflects only those funds that flow through the city budget, which is why this total differs from the $850 million figure published in the de Blasio Administration’s ThriveNYC report.2All years are city fiscal years, unless otherwise noted.

3This share is not more precise because how each school funds its support staff is unique.

4Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Behavioral Health Barometer: United States, 2014. HHS Publication SMA-15-4895. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015.

5The relationship between behavioral health issues and having a low income (and lacking insurance) is complex as the issues compound each other. Those with stressful situations may be more likely to develop behavioral health issues and those with behavioral health issues may be more likely to have very low incomes. National Institute of Behavioral Health. Statistics: Any Disorder Among Adults. Retrieved October 2015

6Substance Abuse and Behavioral Health Service Administration. “Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use & Health: Summary of National Findings.”

7National Institute of Behavioral Health. Statistics: Any Disorder Among Adults. Retrieved October 2015

8Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Behavioral Health Equity Barometer: United States, 2014. HHS Publication SMA-15-4895EQ. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015.

9Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Mental Illness among NYC Adults, NYC Vital Signs, 14(2) June 2015.

10McGinty, E et al. “Federal Parity Law Associated With Increased Probability Of Using Out-Of-Network Substance Use Disorder Treatment Services,” Health Affairs, August 2015 34(8): 1331-1339.

11The Affordable Care Act (2010) requires all Medicaid, Medicare, and private plans offered on exchanges to cover both mental health and SUD treatment, but plans may limit the amount and type of services covered. New York State’s Timothy’s Law (2008) requires most employer sponsored plans to cover a minimum amount of acute mental illness treatment, but the requirements are limited and focused on hospital-based treatment for serious mental illness. The Mental Health Parity Act (2008) requires all plans to cover mental health treatment to the same extent as they do treatments for physical illnesses, but defining “parity” can be difficult. Medicare—the federally administered and funded health insurance plan for all adults age 65 and older—limits coverage of inpatient and outpatient mental health and SUD treatment on a lifetime and annual basis, respectively, and requires co-payments for care. Medicaid—the state-run health insurance plan for low income adults and children—covers both mental health and SUD treatment with some limitations and minimal co-payments.

12Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, Pincus H. “Acceptance of Insurance by Psychiatrists and the Implications for Access to Mental Health Care.” JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):176-181.

13Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Community Health Survey 2014. NYS Medicaid Enrollees & Expenditures by County, 2013. American Community Survey 2013.

14Supportive Housing Network of New York.

15Frank, Richard G. and Glied, Sherry. “Changes in Mental Health Financing Since 1971: Implications for Policymakers and Patients”. Health Affairs May 2006; 25(3): 601-613.

16Community Mental Health Act (1963). President Kennedy’s remarks at the signing of S.1576, October 31, 1963.

17Unlike the public institutions treating mental illness, inpatient institutions treating substance use disorders (including alcoholism and narcotics addiction) have historically been private institutions, paid by individuals and eventually by health insurance programs. Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous and other peer-led groups have long dominated outpatient addiction treatment, but the licensing of addiction counselors in 1974 paved the way for more community-based SUD treatment and support programs.

18These 25 psychiatric institutions now receive some Medicaid funding. The program is barred from covering services provided by state psychiatric facilities for people older than 21 and younger than 65, so only youth and seniors may be covered. Other Medicaid financing of state psychiatric facilities comes through Disproportionate Share Hospital funds ($600 million in 2011 in New York State), and federal waivers from the Center for Medicaid and Medicare to support managed care programs.

19Callahan v. Carey (1981) requires New York localities to provide emergency shelter for single adults that need it. Federal funding for supportive housing organizations came from the McKinney Homeless Housing Assistance Program and the Low Income Housing Tax Credit beginning in the 1980s. State and city funds came from a variety of smaller support grants to fund community residences and single-room-occupancy housing in the 1970s and 1980s.

20Budgeted figures are used instead of actual spending figures because spending may be delayed due to contracting or other issues. Budgeted figures allow for the easiest comparison between years.

21Funding for direct city contracts with behavioral health organizations ($393 million) differs from total contract amounts to the public hospital system and other providers ($439 million) because this section does not include the public hospital contract for behavioral health services in jails ($29 million) or administrative contracts ($18 million).

22DOHMH’s 2015 budget includes $257 million in contracts with behavioral health organizations. The previous section says DOHMH accounts for $245 million of the city’s contracts with behavioral health organizations because approximately $12 million of the total budget funded administrative costs, rather than services.

23For those beneficiaries in managed care Medicaid, the state outsources the administration and payment of most of their medical care to private health insurance companies, both to make costs more predictable and because of anticipated improvements in care coordination. However, the state still pays providers on a fee-for-service basis for some services that are excluded (also known as “carved out”) from managed care agreements and for the care of beneficiaries not enrolled in managed care.

24The vast majority of the ThriveNYC initiatives and funding focus on services for people with mental illness and substance use disorders and do not include care for those with developmental disabilities.

25From 2005 through 2015 behavioral health funding remained stagnant in real dollars and increased slightly in nominal dollars.

26This 2016-2019 four year total includes $35 million in spending in 2015 for some of the first initiatives of the Mayor’s Task Force on Behavioral Health and the Criminal Justice System

27The Mayor’s Fund to Advance New York City is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that develops public-private partnerships and serves as a means for private organizations to fund public programs.

28“NYC City Council Response to the FY 2017 Preliminary Budget & FY2016 Preliminary Mayor’s Management Report,” New York City Council, April 2016.

29The New York City Council’s Committee on Contracts held an oversight hearing on this topic in April 2016.

Receive notification of free reports by e-mail