February 2019

Admissions Overhaul:

Simulating the Outcome Under the Mayor’s Plan For Admissions to the City’s Specialized High Schools

PDF version available here.

Summary

One of the most contentious issues facing New York City’s public schools is the debate around school integration. The proposal to alter the admissions process for the city’s eight specialized high schools is currently among the most controversial elements of this public discussion. What if the de Blasio Administration’s proposal to eliminate the Specialized High School Admissions Test and instead base admissions on factors such as students’ ranking in the top 7 percent of their middle school and top 25 percent citywide (using grades and scores on the state’s assessment tests) had been in place for school year 2017-2018? How different would the demographics and level of academic achievement of the students offered placements at the specialized high schools have been?

IBO has simulated what offers to the incoming ninth grade class in 2017-2018 would have looked like. Even if the admissions process is altered, the composition of the specialized high schools will depend on which schools students ultimately choose to attend. Among our findings:

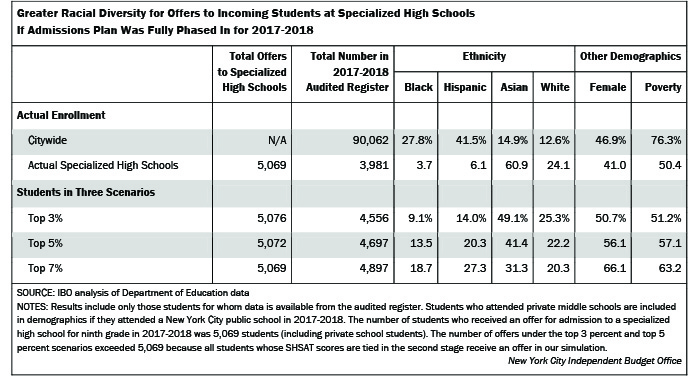

- About 19 percent of admissions offers would have gone to black students, compared with the less than 4 percent who actually attended specialized high schools in 2017-2018. Hispanic students would have received about 27 percent of admission offers, compared with the 6 percent of Hispanic ninth graders who attended the schools last year.

- The number of Asian students receiving admissions offers would have fallen by about half, to just over 31 percent, while offers to white students would have remained relatively flat.

- Substantially more female students would have received offers to attend the specialized high schools. Female students would have comprised 66 percent of the students receiving offers compared with the 41 percent of female ninth graders who actually attended last school year.

- Students in poverty would have made up 63 percent students offered admission to the specialized high schools, compared with the roughly 50 percent who attended ninth grade at the specialized schools last year.

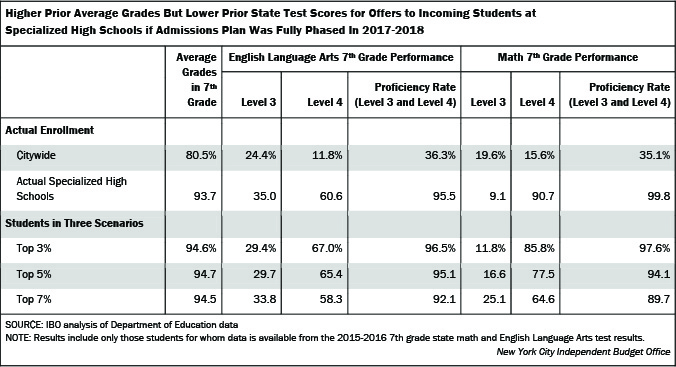

- Students offered admissions would have had slightly higher grades on average than those who entered the specialized high schools in 2017-2018. But scores on the state’s English Language Arts and especially math tests were higher among the ninth graders who attended the specialized high schools last year than the scores of those who would have received offers under the proposed admissions plan.

While roughly 73 percent of all students who under the proposed changes would have received an offer to a specialized high school in 2017-2018 attended a public high school ranked among the top quarter in the city, just 56 percent of black and Hispanic students among that group did so.

Last June, Mayor Bill de Blasio and Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza announced a proposal to change the admissions process for the city’s specialized high schools away from the current Specialized High School Admissions Test (SHSAT) towards a combination of metrics, including New York State assessment scores, middle school grades, and class rank. The proposal is an attempt to increase the diversity at the schools—particularly in terms of the shares of black and Hispanic students—and move away from admissions based on a single test that students must opt to take.

Implementing this change for all eight specialized high schools included in the current proposal would require legislation in Albany to amend the State Education Law, which currently stipulates that specialized high schools can only use the SHSAT as the sole admissions criteria. Although the statute explicitly points to three that currently use the admissions test (The Bronx High School of Science, Stuyvesant High School, and Brooklyn Technical High School), current law also authorizes the Department of Education (DOE) to designate other schools as specialized high schools that are thus required to use the SHSAT as the sole admissions criteria as well. Five additional schools fall into this category: The Brooklyn Latin School; High School for Mathematics, Science and Engineering at City College of New York; High School of American Studies at Lehman College; Queens High School for the Sciences at York College; and Staten Island Technical High School.1

Under the current system, offers to the specialized high schools are distributed to students who received the highest scores on the SHSAT, taking student choice into account. First, students are ranked in decreasing order based on their scores on the SHSAT. Then, beginning with the highest-scoring student, each student is given an offer to their first choice specialized high school. The process of moving down the list of top-scoring SHSAT test-takers continues and if there are no remaining offers to a student’s first-ranked specialized high school, that student would receive an offer to their second-ranked specialized high school.2 The process ends once all offers are distributed to the highest-scoring SHSAT test-takers for whom seats are available at one of their ranked choices. It is important to note that this process runs separately from the main high school choice process where students rank up to 12 choices among all the other high schools in the city. While taking the SHSAT is a prerequisite for students who currently opt into the specialized high school selection process, there are no prerequisites for students who wish to participate in the main high school choice process.

The proposed changes to the current admissions process were detailed in Assembly Bill 10427A, which was introduced the same day the new proposal was formally announced. The bill included a plan to phase out the SHSAT over two years, and to instead offer seats at specialized high schools to eighth graders who meet specific academic criteria.3 This includes ranking in the top of their middle school class based on a composite score that takes average grades (with a weight of 55 percent as determined by the DOE) and performance on the New York State tests (with a weight of 45 percent) into account; in addition, students must also score in the top quartile of all New York City public school eighth graders.

Testing the Results. IBO simulated what offers to the incoming class of ninth graders in school year 2017-2018 would have looked like under three different scenarios—the top 3 percent, top 5 percent, and top 7 percent of students from each traditional public or charter middle school based on a composite score (see appendix for more details on methodology)4. These students also had to rank among the top quartile of all New York City public school eighth graders citywide in terms of composite score. Each of the three scenarios should be viewed as its own steady-state; that is, each scenario represents all offers to the specialized high schools as if that scenario was the policy in place for the entering 2017-2018 ninth grade class. As a result, each of the three scenarios reflect offers to ninth graders in only that one year; this analysis does not consider multiple or sequential years.

The results from the top 7 percent scenario represent what the Mayor and Chancellor’s new admissions system would look like if it had been fully phased in for offers to students entering specialized high schools in the 2017-2018 school year. With this report, IBO adds to existing studies that have explored alternative admissions criteria for the specialized high schools.5 In addition to reporting on the demographic composition of offers to the specialized high schools and academic incoming student performance under these simulations, IBO also looked at what middle schools those students would have come from and what high schools those students actually attended in 2017-2018.

Under the proposal, the SHSAT would be phased out over two years. The top 3 percent of students from each public middle school would receive an offer in the first year. In the second year, the top 5 percent of students from each public middle school would receive an offer. In the first two years, after the top 3 percent and 5 percent of students are given offers, any remaining offers would be distributed to top-ranking SHSAT test-takers—including those who had not received an offer based on their composite score as well as private school, special education, and alternative middle school students who took the SHSAT. In the third year, when the SHSAT would be phased out, the top 7 percent of students from each public middle school would receive an offer, with any remaining offers distributed by random lottery to students with average grades of 93 or higher.6 IBO followed this methodology for the three scenarios.

Public Debate.The announcement in June has spurred intense public debate about the benefits and drawbacks of the proposed changes to admissions at the specialized high schools. Proponents contend that by incorporating multiple criteria as a basis for admission, especially grades and standardized tests that are readily available for all students citywide, the cohort of students receiving offers would be more demographically diverse. Some studies have documented the importance of using multiple criteria to accurately predict future student success at both the high school and college levels.7 Furthermore, some studies—including one focused on performance at the specialized high schools—have found that grades provide a better predictor of future student success compared with performance on standardized tests.8 Additionally, since the academic criteria in the proposal would rely on New York State tests (which are routinely taken by each student) as opposed to the SHSAT (which students must elect to take), all students would have equal access to the specialized high school admissions process—including high-performing students who are less likely to take the exam in the first place (girls, students in poverty, and Hispanic students).9

Those who oppose the proposal contend that it would increase the possibility of admitting students who might not be as prepared for the specialized high schools’ demanding curriculum. Because the proposal would allocate offers based on students’ relative ranking within their school, some students who would have otherwise not received an offer based on their absolute performance would now receive an offer. Conversely, some high-performing students who attend a middle school with a large share of other high-performers might lose out on an offer if they do not rank in the top of their class.10 Additionally, some specialized high school alumni associations have argued that students who are not proficient on the state tests would gain admission to the specialized high schools, threatening the reputation of the schools as among the most elite institutions in New York City. Finally, some argue that the move away from admissions based on the SHSAT in favor of the New York State tests would potentially provide admission to students who may not be able to handle the rigorous curriculum at the specialized high schools, some of which have a heavy focus on math and science.11 Parents at a recent Community Education Council meeting in Manhattan’s District 2—which accounts for a disproportionately larger share of offers to specialized high schools relative to its share of eighth graders in the city—cited several of these points as grounds for opposing changes to admission at the specialized high schools.12

The greatest unknown factor related to the Mayor and Chancellor’s proposed policy is how it will affect students’ choices for high school. While the proposed policy would affect which students would receive an offer to a specialized high school, perhaps equally important is which schools students decide to rank among their choices. And even then, some students who receive an offer from a specialized high school do not choose to attend. Among students coming from public middle schools, 18.0 percent who received an offer to a specialized high school as an incoming student for 2017-2018 chose not to attend. In earlier work, IBO has documented that students are generally matched to their top choices, so whether the proposal would result in changes in the actual composition of the incoming class at the specialized high schools would depend upon whether students who would receive offers would actually choose to accept them.13 Given the polarized debate about the proposal, IBO investigated how the profile of students would change under three different scenarios.

| The Top Quartile Threshold for Eligibility

When selecting students who would receive an offer to specialized high schools under the top 3 percent, top 5 percent, and top 7 percent scenarios, the proposed policy stipulates that student must also score in the top quartile citywide in terms of their composite score. The implication is that it provides a citywide “floor” for student achievement, such that students must meet the requirement for an absolute standing among all students in the city in addition to meeting the requirement for their relative standing in their school. IBO found that the citywide threshold filtered out few of the more than 5,000 students in the 2017-2018 incoming specialized high school class—just 3 students in the top 3 percent scenario; 7 students in the top 5 percent scenario; and 35 students in the top 7 percent scenario. Part of the reason why this threshold does not filter out more students is the way in which grades are factored into the composite score. While performance on the state English Language Arts and math tests is considered relative to citywide results, performance as measured by average grades is considered at the school level. Therefore, the composite score is a blend of students’ relative standing citywide (in terms of state test performance) and students’ relative standing within their school. Although the citywide threshold for the composite score appears to be a way to institute an absolute threshold across the city, in practice the way the threshold is calculated largely precludes that from happening. |

Changes in Demographics and Performance of Incoming Students

Comparing student demographics of those who would receive offers across the three scenarios with ninth graders who actually attended specialized high schools in school year 2017-2018, IBO found that racial diversity would increase while the change in performance of incoming students would depend on how performance was measured. Incoming students’ average grades in seventh grade in the four core subjects (English, math, social studies, and science) would increase slightly across all three scenarios. Under the top 7 percent scenario (if the new system was fully in place), however, average seventh grade state test scores of students who receive offers would be lower than the average for specialized high school students in 2017-2018, especially when considering performance on the state math test.

We also looked specifically at the three different subsets of students who were among the 500 lowest-scoring in terms of three metrics—average grades in seventh grade, seventh grade state math proficiency rating, and seventh grade state English Language Arts (ELA) proficiency rating. Among those students, we found that average grades would increase but there would be declines in proficiency rates in both subjects, especially in math, among the lowest-scoring students receiving offers if the new system was in place in 2017-2018.

Demographic Changes. IBO compared the demographic composition of the specialized high schools under each of the three scenarios with the actual demographic composition of the ninth grade class in specialized high schools in 2017-2018.14 We found that:

- More black and Hispanic students would get offers. Under the top 7 percent scenario, the share of black students receiving offers would increase by five times and the share of Hispanic students receiving offers would increase by more than four times compared with the share of those groups that actually attended a specialized high school in 2017-2018. If the new system was fully in place, black and Hispanic students would make up roughly 19 percent and 27 percent, respectively, of all students receiving offers to the specialized high schools. Although the share of offers to black and Hispanic students would also increase under the top 3 percent and top 5 percent scenarios, the increases are less steep; for example, compared with the respective shares of incoming students who actually attended a specialized high school, the share of offers to black students under the 3 percent scenario would be about 2.4 times greater and the share of offers to Hispanic students would be a little more than double.

- Fewer Asian students would get offers. Just over 31 percent of offers would go to Asian students if the plan was fully phased in, compared with 60.9 percent of ninth graders enrolled in specialized high schools in 2017-2018. Under all three scenarios, Asian students would still comprise the largest share of offers.

- Roughly the same number of white students would get offers. Under the top 7 percent scenario, the share of white students receiving offers would be nearly 4 percentage points lower than the share of incoming white students at the specialized high schools in 2017-2018, from 24.1 percent last school year to 20.3 percent if the new program was fully in place. Under the top 3 percent scenario, however, the share of offers going to white students would be slightly greater than the actual share of incoming white students at specialized high schools.

- More girls would receive offers and under all three scenarios they would account for the majority of students receiving offers. In the top 7 percent scenario, girls would receive two-thirds of all offers, compared with just 41 percent of students who actually attended specialized high schools in 2017-2018.

- More students in poverty would receive offers.15 In 2017-2018, students in poverty comprised about half of all incoming students to specialized high schools; that share would increase to 63 percent if the program was fully phased in for 2017-2018.

Changes in Incoming Student Performance. Based on students’ average grades in seventh grade and performance on seventh grade state standardized assessments, IBO compared the profile of incoming student academic achievement of students who would receive an offer to a specialized high school under each of the three scenarios with the achievement of the incoming ninth grade class in 2017-2018 in specialized high schools. Students’ proficiency ratings on the state ELA and math exams are divided into four levels: 1 (well below proficient in standards), 2 (partially proficient in standards), 3 (proficient in standards), and 4 (excel in standards). The total number of students deemed proficient in standards is the sum of level 3s and level 4s. We found that:

- Incoming students’ average grades in seventh grade would increase slightly (by less than 1 percentage point) compared with the average for ninth graders who attended a specialized high school in 2017-2018.

- The share of level 3s and level 4s in ELA would decrease slightly. If the new plan was fully in place for 2017-2018, the share of level 3s and level 4s in ELA would decrease by about 2 percentage points. In contrast, under both the top 3 percent and top 5 percent scenarios, the share of level 3s in ELA would decrease by a little more than 5 percentage points while the share of level 4s in ELA would increase by more than 5 percentage points.

- The share of level 3s in math would increase and the share of level 4s in math would decrease under all three scenarios. If the new plan was fully phased in for 2017-2018, the share of level 3s in math would almost triple, up to a quarter of offers, while the share of level 4s in math would decrease by more than 26 percentage points compared with the performance of incoming students who attended specialized high schools in 2017-2018. Although the share of level 3s would increase and the share of level 4s in math would decrease under the top 3 percent scenario as well, the changes are less steep; for example, compared with the respective shares of incoming students who attended a specialized high school in 2017-2018, the share of level 3s would increase by less than 3 percentage points and the share of level 4s would decrease by 5 percentage points.

- The proficiency rate—the share of level 3s and 4s—would decline slightly in ELA and more so in math compared with ninth graders who attended a specialized high school in 2017-2018. Almost 90 percent of students would be proficient in math if the new system was fully phased in for 2017-2018, although virtually all ninth graders who attended a specialized high school in 2017-2018 were proficient in math. That decline would be less steep under the top 3 percent and top 5 percent scenarios when more than 97 percent and almost 94 percent, respectively, of students who would receive an offer in 2017-2018 were proficient in math in seventh grade. Declines in the ELA proficiency rate would be smaller than those for math; under the top 7 percent scenario, more than 92 percent of students who would receive an offer in 2017-2018 were proficient in ELA in seventh grade compared with over 95 percent of students who attended a specialized high school in that year. Under the top 3 percent scenario, however, the share of students who were proficient would actually increase by 1 percentage point relative to the share of students who attended a specialized high school in 2017-2018.

Because some opponents to the proposed changes have expressed concern about the incoming performance of the lowest-achieving students who would receive an offer under the new plan, IBO also looked at the 500 lowest scoring students. We analyzed the three different subsets of students who would receive an offer under each of our three scenarios but were also among the 500 lowest scoring in terms of three metrics: average grades in seventh grade, seventh grade state math proficiency rating, and seventh grade state ELA proficiency rating. We compared the 500 lowest-scoring ninth graders for each of the three metrics in each of the three scenarios against the 500 lowest scoring ninth graders who attended a specialized high school in 2017-2018. We found that:

- Average grades in seventh grade among the 500 lowest-scoring students under each scenario would look similar or better relative to the distribution of ninth grade students who actually attended a specialized high school.

- In the top 7 percent scenario, 77.0 percent of the lowest scoring incoming students would not be proficient in English, compared with 32.0 percent of the lowest scoring incoming students at specialized high schools in 2017-2018. In the top 3 percent scenario, the same share of the lowest-scoring students would not be proficient as those who actually attended the specialized high schools in 2017-2018.

- The comparison is even starker for math if the new plan was fully phased in for 2017-2018: none of the lowest scoring incoming students would be proficient in the top 7 percent scenario compared with just 1.2 percent of the lowest scoring incoming students who actually attended specialized high schools. Even in the top 3 percent scenario, more than 21 percent of the lowest-scoring students would not be considered proficient.

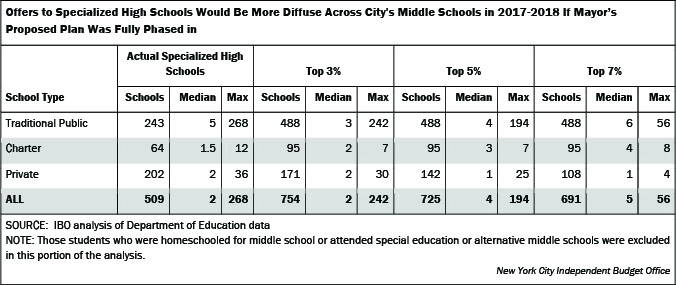

Middle School Shift. As noted in the previous section, the demographics of the incoming ninth graders who would receive offers would change relative to the demographics of the ninth graders who attended specialized high schools in 2017-2018. These shifts are a reflection of how offers to students would be spread out more evenly across public middle schools, rather than the highly concentrated distribution of offers among students in the highest performing middle schools under the current system. IBO found that the distribution of offers would be more even across the city’s middle schools if the proposed plan was fully phased in for 2017-2018. As a result of a more even distribution of offers, the number of middle schools with students who would receive offers would increase while the maximum number of offers received by students at any one middle school would decrease. The share of offers to students who attended traditional public middle schools would increase slightly, the share of offers to charter middle schools would increase more strongly, and the share of offers to private middle schools would decrease as private school students would only be eligible to receive an offer after offers are allocated to students from public middle schools.

Based on students who would receive offers in the three scenarios, we tallied the total number of students from each middle school that would receive an offer to a specialized high school in 2017-2018. We first looked at all middle schools and then disaggregated by type of middle school (traditional public, charter, or private).

A plot of the cumulative share of offers to specialized high schools against the cumulative share of middle schools with students receiving offers shows that if the proposed plan was fully phased in for 2017-2018, it would have resulted in a more even distribution of offers across middle schools than the current system. Looking horizontally from the perspective of the share of offers to specialized high schools, in 2017-2018, 50 percent of offers to specialized high schools went to students from just 5.7 percent of middle schools in the city. If the proposed plan had been fully phased in, the share of middle schools with students receiving offers would have increased to 16.2 percent of middle schools. Moving farther up the vertical axis, under the current system, about 80 percent of offers to specialized high schools in 2017-2018 went to students at about 20 percent of middle schools. Under the top 7 percent scenario, the share of middle schools with students receiving offers would have increased to roughly 49 percent of middle schools. Under the current system, 509 middle schools had students who received offers to specialized high schools. In the top 7 percent scenario, the total number of middle schools with students receiving offers would increase to 691 schools, an increase of 182 schools, or more than 35 percent.

More traditional public and charter schools would have had students receiving offers in 2017-2018 than under the current system. Under the current system, 243 traditional public schools, 64 charter schools, and 202 private schools had students who received offers to specialized high schools. Among traditional public schools, the number of schools with students receiving offers would more than double to a total of 488 schools (up from half to virtually all 490 traditional public middle schools) under all three scenarios. The number of charter schools with students receiving offers would increase by almost 50 percent to a total of 95 schools compared with the current system, increasing from 66.7 percent to 99.0 percent of all 96 charter middle schools. Conversely, the number of private schools with students receiving offers under the top 7 percent scenario would decrease by over 46 percent to a total of 108 schools.

The median number of students who would receive an offer from any one school if the proposed plan was fully phased in for 2017-2018 would increase for traditional public and charter schools and decrease for private schools.

Across all school types and all three scenarios, the maximum number of offers to students from any one middle school would decrease. Based on the top 7 percent scenario, the decrease would be greatest for traditional public middle schools, where the maximum number of offers to students from any one school would decline by 79.1 percent (from 268 offers at one middle school to 56 offers at one middle school), and private schools, which could experience an 88.9 percent decline (from 36 offers at one middle school to 4 offers at one middle school).

When we looked at all offers across middle schools by school type, we found that if the proposed plan was fully phased in for 2017-2018, the share of offers to students from traditional public middle schools would have increased slightly, and the share of offers to students from charter middle schools would also have increased more substantially compared with the current system. The share of offers to students from private middle schools would have decreased substantially, as they are only eligible to receive an offer after public school offers are made. The share of offers to traditional public middle schools increased from 83.8 percent under the current system up to 89.1 percent under the top 7 percent scenario. Similarly, the share of offers to charter middle schools would more than double from 3.0 percent up to 7.6 percent while the share of offers to private middle schools would decrease substantially from 13.2 percent down to 3.3 percent.

Where Did Students in the Scenarios Actually Go to High School in 2017-2018?

The previous sections have described offers to specialized high schools based on a proposed alternative to the current specialized high school admissions system using three scenarios. In our analysis of the three scenarios, we are unable to account for the role of student choice in the process mainly because there is no way to know how the proposed changes might affect students’ choices if they were implemented. However, because we are using the cohort of students who entered ninth grade in 2017-2018, we can observe the high schools that students who would have received offers under our three scenarios actually chose to attend last year. We offer this analysis not as a counterfactual to where students might have gone but rather as an observation of the academic profile of the traditional public or charter high schools that the highest ranking students in our scenarios actually chose, given the options available at that time.

AAmong the students who would have received an offer in the top 7 percent scenario and went on to attend a public high school in New York City, IBO found that almost three-quarters of students attended schools ranked in the top quarter of all public high schools in terms of the share of their graduates who were college ready, indicating that many top-performing students are gaining access to high-quality schools—whether specialized high school or not—under the current system.16 On the other hand, about a quarter of those students did not. Furthermore, when we looked at student-level differences by ethnicity, we found that much smaller shares of black and Hispanic students who would have received offers if the new plan was fully phased in for 2017-2018 actually attended top-ranked high schools whereas higher shares of white and Asian students did.

The proposed changes could have the greatest impact for top-performing black and Hispanic students, who were least likely to attend a top-ranked high school in the city in 2017-2018. However, student choice is the largest unknown quantity in this analysis and in the broader discussion around changes to admissions at the specialized high schools. Actual changes to enrollment at the specialized high schools depend on whether students who would receive offers would actually choose to accept them.

IBO looked at the 2016-2017 share of students that graduated college-ready for each of the 460 traditional public or charter high schools in the city in the 2017-2018 school year. We ranked schools in decreasing order based on their college-ready graduation rate. We first identified the eight specialized high schools and found that each had a college-ready rate of 97.3 percent or higher. Then we identified all other high schools that also had a college-ready rate of 97.3 percent or higher. Next, we identified high schools with a college-ready rate between 63.4 percent and 97.3 percent; 63.4 percent reflects the lowest college-ready rate among the top quarter of all city high schools. We then identified high schools with a college-ready rate between 44.4 percent and 63.4 percent; 44.4 percent reflects the average college-ready rate across all city high schools. Finally, we identified schools with a below-average college-ready rate of less than 44.4 percent.17

Among the samples of students in each of the three scenarios who attended a traditional public or charter high school in New York City in 2017-2018, IBO analyzed the academic profile of the high schools they attended. We additionally looked at differences by racial group. We found that:

- Just more than one-quarter of students in the top 7 percent scenario actually attended a specialized high school. That share increased to roughly half of students in the top 5 percent scenario and more than two-thirds of students in the top 3 percent scenario.

- Over 37 percent of students who would have received an offer to specialized high schools if the new plan was fully phased in for 2017-2018 attended a high-performing high school with a college-ready rate of 97.3 or higher, even if it was not a specialized high school. Under the top 3 percent scenario, 77.2 percent of students attended a high school with a college-ready rate of 97.3 or higher.

- About 73 percent of students who would receive an offer under the top 7 percent scenario attended a high school in 2017-2018 that was ranked in the top quarter of all city high schools (college-ready rate of 63.4 percent or higher). On the other hand, one-quarter of students under the top 7 percent scenario attended a high school in 2017-2018 with a college-ready rate below 63.4 percent. Under the top 3 percent scenario, 91.2 percent of students attended a high school in 2017-2018 that was ranked in the top quarter of all city high schools.

- Over 85 percent of students receiving offers under the top 7 percent scenario attended a high school with a higher-than-average college ready rate (44.4 percent), which meant that about 14 percent of those students attended a high school with a college-ready rate below the city average. Under the top 3 percent scenario, over 95 percent of students attended a high school with a college-ready rate of 44.4 percent or higher.

Looking by racial group, we found that:

- While a majority of students within each racial group attended a high school in the top quarter of city high schools based on the top 7 percent scenario, a substantially smaller share of black and Hispanic students did (roughly 56 percent within each group) compared with white and Asian students (roughly 81 percent and 90 percent, respectively).

- The differences were even starker when we looked at students who attended a high school in 2017-2018 with a college-ready rate of 97.3 or higher—a rate equivalent to that in specialized high schools. Just 12 percent and 16 percent, respectively, of black and Hispanic students attended such a school in 2017-2018 whereas larger shares of white and Asian students did (about 46 percent and 63 percent, respectively).

An Ongoing Debate

Our report demonstrates the potential changes in the racial composition and prior achievement of students entering specialized high schools based on the June 2018 de Blasio Administration proposal if students choose to attend specialized high schools when presented with the offer. If they do, and if the proposal was fully phased in for the 2017-2018 school year, our analysis indicates that there would have been a more even distribution of offers across middle schools, with the number of traditional public and charter middle schools with students receiving offers increasing substantially, leaving fewer offers for private middle school students. Our report demonstrates the potential changes in the racial composition and prior achievement of students entering specialized high schools based on the June 2018 de Blasio Administration proposal. Assuming students choose to attend specialized high schools when presented with an offer, and if the proposal was fully phased in for the 2017-2018 school year, our analysis indicates that there would have been a more even distribution of offers across middle schools. The number of traditional public and charter middle schools with students receiving offers would have increased substantially, leaving far fewer offers for private middle school students. When we looked at which high schools students who would have received offers under the top 7 percent scenario actually attended in 2017-2018, we found that overall about 73 percent attended high schools ranking in the top quarter by performance—specialized high school or otherwise. However, just 56 percent of black and Hispanic students who would have received offers attended high schools ranked in the top quarter.

It is clear that there are other high-performing high schools in the city that high-achieving middle school students can and do access after eighth grade, and we have no way of knowing how or if that would change. The proposed changes have the potential to benefit high-achieving black and Hispanic students the most, assuming students choose to accept offers. If changes to admission to the specialized high schools are implemented, how students’ choices change will dictate whether the goal of increased racial diversity will be realized.

With the 2019 New York State legislative session now underway, it remains to be seen which, if any, proposals for changes to admission for the specialized high schools are introduced. By law, any changes to admissions to three of the specialized high schools—The Bronx High School of Science, Stuyvesant High School, and Brooklyn Technical High School—would require legislative approval. However, changes to admission at the other five schools that the DOE has designated as specialized high schools do not require legislative approval. So far, the Mayor and Chancellor have committed to considering all eight schools together, but that may change.

In the meantime, the de Blasio Administration plans to expand the Discovery program—targeted to provide admission to students who just miss the SHSAT cutoff with additional support—this summer. Over two years, the DOE plans to increase the number of specialized high school seats allocated to Discovery recipients from roughly 4 percent to 20 percent, reducing the number of available offers through the traditional application process. Based on the plan, eligibility requirements to the program will be amended to target students attending high-poverty middle schools. Although a lawsuit has stalled the DOE’s implementation of the plan, the Discovery program remains a tool that the DOE can use to allocate offers to the specialized high schools outside of the traditional process.

The Mayor recently indicated he is seeking feedback from parents on the proposed changes. Concerns will likely be raised on a number of fronts. The proposal has already elicited pushback from many parents in the Asian community, which tends to send large numbers of students to the specialized high schools under the current admissions system. Some Asian American advocates and parents claim that changes to the Discovery program would also discriminate against them. In addition, our results show that offers to students from private middle schools would be substantially reduced based on the current proposal. Moreover, students who are homeschooled or attend special education or alternative middle schools could lose out on the opportunity to attend a specialized high school because their schools are not considered “traditional” public schools.

The debates around school integration in New York City continue to be polarized, and the ongoing debate around changes to admissions to specialized high school is no exception.

Report prepared by Sarita Subramanian

Appendix: Methodology

Assembly Bill 10427A stipulates that the New York City Schools Chancellor will determine which academic factors are to be considered, but it must include academic course grades and standardized test scores. IBO followed guidance provided by the New York City Department of Education to calculate the composite score for each student, incorporating each student’s seventh grade math and English Language Arts proficiency ratings on the 2015-2016 New York State test and average grades across the four core subjects (English, math, social studies, and science). Proficiency ratings range from 1.0 to 4.5 and academic course grades are on a 60-100 point scale. In order to calculate the composite score, IBO first calculates the average proficiency rating and the average grade for each student, and then calculates standardized scores (commonly referred to as z-scores). Z-scores for average proficiency ratings are calculated across the city. Z-scores for average grades are calculated within each school, to account for grading differentials across schools.

The composite score combines students’ average proficiency rating and average grades. Each student’s average proficiency rating relative to the citywide average is given a weight of 45 percent of the student’s composite score. Each student’s average grades relative to the school average is given a weight of 55 percent of the student’s composite score.

Each of the three scenarios were run in two stages, with the first stage of offers being reserved for the share of students (3 percent, 5 percent, or 7 percent) with the highest composite scores in each traditional public or charter middle school. Middle schools serving student with disabilities (D75) and alternative middle schools (D79) are excluded from stage one. If after the first stage the number of offers remained below 5,069—the total number of ninth grade offers to the eight specialized high schools in 2017-2018—we implemented a second stage. For the top 3 percent and top 5 percent scenarios, the second stage filled any remaining offers with the top-ranked SHSAT test-takers who had not received an offer based on their composite score, including both public and private school students. It is important to note that the sample of students in the first stage for both the top 3 percent and top 5 percent scenarios includes all students for whom grades and test scores are available, whereas the second stage remains similar to the current system—students must opt in (take the SHSAT) in order to be eligible to receive an offer. For the top 7 percent scenario, when the SHSAT is fully phased out, the second stage filled any remaining offers by a random lottery of all students with average grades of 93 or higher. Only in the top 7 percent scenario is there no requirement for students to opt in to be considered eligible for an offer to a specialized high school in the second stage. Private school students, as well as homeschooled students and those attending D75 or D79 middle schools, would only be eligible to receive an offer in stage two of all three scenarios. In all cases of ties, IBO considered all students with the same score to be eligible to receive an offer. Student school choice was not simulated and we modeled offers to all eight specialized high schools together as if they were one school.

Endnotes

1Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts is also designated as a specialized high school, but admissions are based on a competitive audition.

2The number of offers for each school exceeds the number of students the school expects to enroll because schools anticipate that some share of offers will not be accepted. The extent to which offers exceed expected enrollment varies considerably by school; in 2017-2018, The Brooklyn Latin School sent offers to more than twice as many students than actually enrolled, while Staten Island Technical High School sent just two more offers than there were seats available.

3The Assembly bill also outlined changes to the Discovery Program, which provides academic support over the summer to SHSAT-takers who just missed the cutoff score for admission to specialized high schools with the goal of offering a seat to a specialized high school at the end of the program. The Mayor’s proposal would expand the program to 20 percent of seats at each specialized high school up from the current share of 4 percent, and eligibility requirements would be amended to target students attending high-poverty middle schools. This approach is intended to increase diversity at specialized high schools more rapidly than phasing out the SHSAT, and the New York City Department of Education intends to discontinue the program if the SHSAT is phased out.

4IBO’s methodology was also informed by details included in Assembly Bill 10427A as well as prior published work. Corcoran, Sean P. and Baker-Smith, Christine (2015). Pathways to an Elite Education: Exploring Strategies to Diversify NYC’s Specialized High Schools. The Research Alliance for New York City Schools and Institute for Education and Social Policy, NYU, March 2015.

5See Corcoran, Sean P. and Baker-Smith, E. Christine (2018). Pathways to an Elite Education: Application, Admission, and Matriculation to New York City’s Specialized High Schools. Education Finance and Policy, 13(2), Spring 2018, 256-279. Also see Corcoran, Sean P. and Baker-Smith, Christine (2015). Pathways to an Elite Education: Exploring Strategies to Diversify NYC’s Specialized High Schools. The Research Alliance for New York City Schools and Institute for Education and Social Policy, NYU, March 2015.

6While the Assembly bill stipulated a range of the top 5 percent to the top 7 percent from each public middle school, the Mayor and Chancellor are committed to the top 7 percent.

7For example, one study at an elite private secondary school argues in favor of using multiple criteria beyond standardized test scores and grades for admission to school—Grigorenko, E. L., Jarvin, L., Diffley, R., Goodyear, J., Shanahan, E. J., & Sternberg, R. J. (2009). “Are SSATs and GPA Enough? A Theory-Based Approach to Predicting Academic Success in Secondary School.” Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(4), 964–981. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015906.

8For example, one study found that grades in seventh grade are a better predictor for success in specialized high schools in New York City compared with test scores on the SHSAT—Taylor, J. (2018). Fairness to Gifted Girls: Admissions to New York City’s Elite Public High School, presented at American Educational Research Association Conference, New York City, 2018.

9See Corcoran, Sean P. and Baker-Smith, Christine (2015). Pathways to an Elite Education: Exploring Strategies to Diversify NYC’s Specialized High Schools.

10See Lee, J. (2018, June 29). See Where New York City’s Elite High Schools Get Their Students. The New York Times.

11Two recent news articles that have discussed concerns about the potential impact of the proposed changes on incoming student performance on state test scores are: Brody, L. (2018, October 18). Stuyvesant, Other Elite New York Public High Schools Could Admit Students Who Didn’t Pass State Tests. The Wall Street Journal; and Manskar, N. (2018, June 4). Elite High School Alumni to Fight Mayor’s Diversity Bill. New York City Patch.

12See Amin, R. (2018, December 3). Manhattan parents decry proposal designed to diversity city’s most sought-after high schools. Chalkbeat NYC.

13See Nowaczyk, Przemyslaw and Joydeep Roy (2016), Preferences and Outcomes: A Look at New York City’s Public High School Choice Process. New York City Independent Budget Office, March 2016. Also see Nathanson, Lori, Corcoran, Sean, and Baker-Smith, Christine (2013), High School Choice in New York City: A Report on the School Choices and Placements of Low-Achieving Students. The Research Alliance for New York City Schools and Institute for Education and Social Policy, NYU, April 2013.

14IBO also considered the demographic composition of students who received offers to the specialized high schools in 2017-2018 and found that the demographic breakdown was similar to that of the students who actually attended.

15The New York City Department of Education classifies a student in “poverty” if their family qualifies for free or reduced-price lunch on the basis of a take-home form or if eligibility for New York City’s Human Resources Administration benefits has been confirmed.

16The determination for whether a student graduates college- and career-ready varies by student cohort, defined as what year the student entered ninth grade. For the cohort that entered in fall 2013—those who would have graduated on-time in the 2016-2017 school year—there were additional requirements on top of the requirement to obtain a Regents diploma (an Advanced Regents diploma graduate automatically qualifies as college- and career-ready because of the more stringent requirements necessary to obtain the diploma). Students were required to obtain minimum scores on the Common Core aligned ELA and math Regents exams, and to pass an Advanced Placement or other course that earns college credit. See the Graduation Requirements Cards on the Department of Education website for more details.

17The city average is the average college-ready rate in 2016-2017 across all city traditional public and charter schools.

PDF version available here.

Receive notification of free reports by e-mail