December 2013

PDF version available here.

For the

New Mayor and City Council:

A Big Budget Surplus and Even Bigger

Fiscal Challenges Ahead

Through much of

the summer and early fall, it was asserted with some frequency

that New York’s next Mayor and City Council would inherit a

substantial budget shortfall for the upcoming fiscal year along

with other fiscal challenges. Then in November Mayor Bloomberg

released his quarterly update to the city’s financial plan and a

different story emerged: The Mayor projected a sizable surplus

for the current year as well as a balanced budget for next year,

fiscal year 2015.

Based on IBO’s

most recent economic forecast and tax revenue and spending

projections, the city’s near-term fiscal outlook appears even

stronger than expected by the Bloomberg Administration. Under

the contours of the Mayor’s budget plan, IBO anticipates the

city will end the current fiscal year with a surplus of $2.4

billion, $581 million more than projected by the Bloomberg

Administration. We also project a budget surplus of $1.9 billion

in fiscal year 2015, which starts on July 1, 2014.

But there are a

number of challenges ahead that could quickly erode the city’s

fiscal condition. Largest among these challenges may be the cost

of an eventual settlement with the city’s municipal labor

unions, all of which are working with expired contracts. The

Bloomberg Administration’s financial plan assumes the unions

will settle for no back pay for the years without contracts or

raises. A costless settlement for these prior years remains a

long shot as part of an accord with the unions.

Ensuring the

fiscal integrity of the city’s public housing and public

hospitals in the wake of diminishing federal subsidies and

continued fiscal ills is also likely to strain city resources.

Although the recent budget deal in Washington will lessen some

cuts to federally subsidized programs, there will be pressure to

replace lost federal aid with local funds to avert service

cutbacks. And with a new Mayor and City Council taking office,

there may be considerable expectations from issue advocates and

the broader public for new initiatives from City Hall that could

add to local spending.

U.S. and

Local Economic Outlook

Economic

Overview.

Federal fiscal

policy in 2013—the tax increases that took effect in January and

the cuts to federal government spending under the sequester that

took effect in March—created a drag on U.S. economic growth.

(Unless otherwise noted, in this economic outlook section years

refer to calendar years rather than fiscal years.) In the

absence of further contractionary policies in the coming year,

the drag will abate in 2014. With the Federal Reserve’s (Fed)

maintenance of low interest rates, IBO’s forecast an

acceleration of economic growth—to 2.8 percent growth in real

gross domestic product (GDP) in 2014 and 3.4 percent in 2015.

Even with this growth, the U.S. unemployment rate is not

expected to fall below 6.0 percent until late in 2015.

With the addition

of a projected 75,100 jobs to the New York City economy in 2013,

employment in the city reached a new all-time high. IBO

forecasts somewhat less employment growth in the coming

years—the addition of 67,300 jobs in 2014 and an average of

68,400 new jobs in each of the next three years. However,

increases in wages and earnings in the city have not kept pace

with job growth. The composition of the city’s work force has

shifted, and is expected to shift further, towards lower paying

industries.

U.S.

Economy.

The U.S. economy

has continued to grow in 2013, but the pace has been sluggish in

spite of momentum in the housing market and other conditions

conducive to growth. Economic growth has been constrained by

contractionary fiscal policies that took effect earlier in the

year, and by uncertainty caused by the brinksmanship in

Washington over the federal budget and debt ceiling that

resulted in October’s federal government shutdown. IBO projects

a 1.7 percent increase in the nation’s real gross domestic

product for 2013—far less than the 2.8 percent growth in 2012.

The fiscal drag attributable to this year’s tax increases and

spending cuts will begin to abate in 2014 and IBO expects

consumer spending to increase. Barring external shocks to the

economy, further contractionary fiscal policies or more budget

and debt ceiling brinksmanship in Washington, IBO forecasts

faster real GDP growth in the next two years: 2.8 percent in

2014 and 3.4 percent in 2015.

|

Total Revenue

and Expenditure Projections

Dollars in millions |

|||||

|

|

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

Average Change |

|

Total Revenues |

$73,463 |

$74,574 |

$77,313 |

$80,455 |

3.1% |

|

Total Taxes |

45,688 |

48,267 |

50,862 |

53,371 |

5.3% |

|

Total

Expenditures |

73,463 |

72,683 |

77,019 |

79,017 |

2.5% |

|

IBO Surplus/(Gap) Projections |

$- |

$1,891

|

$294

|

$1,438

|

|

|

Adjusted for

Prepayments and Transfers: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total Expenditures |

$74,957 |

$75,133 |

$77,122 |

$79,017 |

1.8% |

|

City-Funded Expenditures |

$53,578 |

$54,903 |

$56,599 |

$57,976 |

2.7% |

|

NOTES: IBO projects a surplus of $2.351 billion for

2014, $581 million above the Bloomberg Administration’s

forecast. The surplus is used to prepay some 2015

expenditures, leaving 2014 with a balanced budget.

Estimates exclude intra-city revenues and expenditures.

City-funded expenditures exclude state, federal and

other categorical grants, and interfund agreement

amounts.

Independent Budget

Office |

|||||

The U.S. economy

has been slow to recover from the Great Recession of 2008 and

2009. By November 2013—after 44 months of near continuous

employment growth—the economy had regained only 85 percent of

the 8.7 million jobs lost over 25 months of contraction. So far

this year (through November), employment has grown by an average

of 189,000 each month, compared with average monthly employment

gains of 179,000 per month during the same period in 2012.

Modest job growth in the private sector coupled with declines in

government employment for much of the period have resulted in

only a gradual decline in the unemployment rate in the last four

years, from 9.9 percent at the recession’s trough (fourth

quarter of 2009) to 7.0 percent in November—still well above the

average 4.6 percent unemployment rate in 2007. Had the labor

force participation rate of the 16-and-over population not

fallen during this period—as discouraged job seekers left the

labor market entirely—there would have been even less of a

decline in the unemployment rate.

The recovery’s

lackluster employment gains and GDP growth have continued even

as conditions favorable to a more robust economic expansion have

been in place for some time. The recession was the start of a

prolonged period of deleveraging by businesses, banks, and

households that strengthened balance sheets. After-tax profit

margins of the corporate sector have reached new highs in the

last few years as businesses have reduced their operating costs.

Banks are also better capitalized than at any point in the last

25 years—the result of more stringent capital requirements in

the wake of the financial crisis and the high profit margins

that low interest rates have enabled.

Since the

beginning of 2012, the household sector’s debt as a percentage

of its disposable (after-tax) income has remained lower than at

any time since 1993. There is considerable pent-up demand for

everything from appliances to cars to homes, much of it coming

from the large number of young adults who during the recession

deferred forming their own households. The improved financial

position of households has stimulated consumer spending,

particularly for autos and other durable goods. Very low

interest rates have increased access to mortgage financing,

stimulated home sales, and finally reversed the long slide in

home prices. As a result, inventories of unsold homes have

declined and housing starts have increased. The improving

housing market and the strength in the stock market have created

a wealth effect that has also boosted spending, especially by

higher income households.

The Federal Reserve’s policy of low interest rates—keeping the federal funds rate on overnight loans between banks near zero and continuing to buy up financial assets to put downward pressure on long-term interest rates (quantitative easing)—has been an essential ingredient of economic growth. Low rates have been vital to the turnaround of the housing market, which had been a major impediment to growth in the aftermath of the Great Recession.

In contrast to

monetary policy, fiscal policy and Congressional brinksmanship

have fanned economic headwinds, substantially reducing GDP

growth in 2013. The elimination of the payroll tax cut and the

increase in marginal tax rates for high-income taxpayers, each

of which took effect on January 1, slowed growth early in the

year. These actions were followed by the previously adopted

across-the-broad spending cuts known as sequestration, which

automatically took effect this March when Congress failed to

agree on a new budget. Later in the year came the extended

negotiations between the Congress and the White House over the

federal budget and debt ceiling, which led to the partial

shutdown of the U.S. government in the first half of October. In

addition to interrupting government operations and pruning

federal contracts with businesses, the shutdown and the

brinksmanship that led up to it undermined consumer confidence.

The Conference Board’s Consumer Confidence Index (a widely used

measure of consumer sentiment) plummeted in October and further

declined in November to reach a seven-month low, negating most

of its rise last spring. The political uncertainty created by

the shutdown has also shaken business confidence and given firms

more reason to postpone hiring and/or to expand capacity.

Despite

unexpectedly strong growth in the third quarter, IBO projects

just 1.7 percent real GDP growth in 2013—the lowest annual rate

since the end of the recession. A spike in inventories—the

highest in three years—accounted for nearly half of the 3.6

percent growth in third quarter GDP. IBO expects much weaker

fourth quarter growth as inventories decline during the holiday

shopping season and as a result of October’s federal government

shutdown. The modest pace of economic growth in 2013 has brought

some improvement in the nation’s unemployment rate, from an

average of 8.1 percent in 2012 to a projected average of 7.4

percent in 2013. Personal income growth, however, has dipped to

a projected 2.9 percent, down from 4.2 percent in 2012. With

unemployment still high, relatively stable oil prices, and slow

growth, the rate of inflation will decline from last year—1.4

percent, compared with 2.1 percent in 2012.

IBO’s forecast

beyond 2013 is premised on no external shocks to the economy,

and no additional harm from fiscal or monetary policy. The

Federal Reserve has indicated that it will continue its

accommodative monetary policy until the unemployment rate falls

below 6.5 percent or inflation appears to be taking hold. Based

on our employment forecast, this suggests that the Fed will

maintain a near-zero federal funds rate through most of 2014.

When the Federal Reserve does decide to wind down its asset

purchases, IBO assumes that it will be able to do so in a slow,

transparent, and orderly fashion—successfully avoiding sudden

spikes in interest rates. Although IBO’s economic forecast was

made before the recent approval of a new federal government

budget, the new agreement is consistent with our assumptions

about fiscal policy. We had assumed that lawmakers in Washington

would avoid another showdown over the federal budget, coming to

an agreement in time to avert the next round of sequestration.

We had also assumed that any new budget agreement would not

substantially change the current stance of fiscal policy,

meaning that any loosening of cuts under sequestration would be

offset by other changes that would leave the total dollar amount

of deficit reduction essentially unchanged. Finally, the

forecast also assumes that there will be no political

brinksmanship when the nation’s debt ceiling needs to be

increased, sometime this spring.

With no new

contractionary fiscal policies being adopted, IBO expects

economic growth to pick up in 2014, as the impact of the 2013

tax increases and spending cuts gradually diminish early in the

year. IBO forecasts 2.8 percent real GDP growth in 2014 and 3.4

percent growth in 2015—the latter growth would be faster than in

any year since 2005. Personal income growth will accelerate from

this year’s modest gain of 2.9 percent to 6.0 percent next year

and 7.0 percent in 2015. Faster growth will bring significant

reduction in the unemployment rate, to an average of 6.7 percent

in 2014 and 6.3 percent in 2015. It also will put upward

pressure on prices. As the unemployment rate approaches the

Fed’s 6.5 percent target—likely towards the end of 2014—we

expect the Fed to gradually increase the federal funds rate in

order to contain inflation. IBO forecasts that the rate of

inflation will remain in the vicinity of 2.5 percent in 2016 and

2017.

IBO expects growth

of both personal income and output to moderate after 2015, with

real GDP growth dipping to 2.9 percent in 2016 and 2017. Despite

slower economic growth, we expect the unemployment rate to

continue its gradual decline, falling below 6.0 percent late in

2015 for the first time since 2008.

Compared with

IBO’s macroeconomic forecast, the Mayor’s Office of Management

and Budget (OMB) projects slightly slower real GDP growth in

both 2014 (2.6 percent versus 2.8 percent for IBO) and 2015 (3.2

percent versus 3.4 percent). In line with a forecast of slower

growth, OMB forecasts higher unemployment than does IBO in 2014

and 2015—7.1 percent and 6.5 percent, respectively, compared

with 6.7 percent and 6.3 percent. With slower growth, OMB also

forecasts lower inflation than IBO in these years–1.5 percent in

2014 and 1.6 percent in 2015. After 2015, the OMB forecast of

real GDP growth remains above 3.0 percent, while IBO’s falls to

2.9 percent in each year.

Risks to the Economic Forecast.

Monetary policy poses a major risk to IBO’s economic outlook.

Unwinding quantitative easing without generating sharp increases

in long-term interest rates will be tricky, as was demonstrated

last summer—interest rates rose when investors (mistakenly)

believed that the Fed was about to reduce its asset purchases.

While the rise in interest rates was temporary and the higher

rates were still quite low by historical standards, it had a

measurable negative impact on consumer spending and home

sales—strength in both these sectors is necessary for more

robust U.S. economic growth.

Another risk is the possibility of a new Congressional showdown over the federal debt ceiling—which looms again in the spring. This would again undermine consumer and business confidence, and potentially trigger another downgrade of U.S. debt. The ability of Congress to come to a timely agreement in recent budget negotiations is a hopeful sign that a showdown can be averted.

IBO’s economic forecast is premised on there being no external

shocks to the U.S. economy, whether from oil prices or economic

disruptions elsewhere in the global economy. Though the current

glut of oil on the market has made the disruption in the supply

of oil less an immediate threat than it has been in recent

years, any sudden increase in the price of oil could greatly

harm economic growth.

A worsening of

economic problems in the European Union countries—which together

make up a substantial share of the global economy and a major

U.S. trading partner—could have a major impact on global trade

and financial markets including those in the U.S. Slow growth or

recession still plagues most European Union countries, and the

current institutional underpinnings of the euro may not be able

to sustain the currency in the long run.

Finally, economic

problems in China, the world’s second largest economy, could

also have a major impact on international trade and finance. The

rapid growth of the Chinese economy in recent years risks

becoming unsustainable, and has resulted in fiscal imbalances

that have only recently been acknowledged. Economic reforms are

on the agenda of Chinese policymakers, but it is not clear if

they can be carried out without major disruptions. Given New

York City’s role as a global financial center, shocks from

financial crises in Europe or China would have a major impact

across all sectors of the city’s economy.

New York

City Economy

New York City’s economic expansion is now four years old, and in that time the city has added 312,000 (corrected number) payroll jobs and established new all-time highs in employment. The job gain is more than double the number of jobs lost during the 2008-2009 crisis and recession. The city’s forward momentum was only briefly interrupted by Hurricane Sandy, and has not been checked (at least in terms of overall jobs growth) by prolonged duress in the city’s financial sector.

IBO forecasts an only slightly diminished pace of growth over

the next four years, with the city economy projected to add

another 67,300 jobs (1.7 percent) in 2014 and an average of

68,400 jobs (1.7 percent) per year from 2015 through 2017.

This forecast incorporates projections for very modest growth in employment and wages in the banking and securities industries, but it is also possible that regulatory changes and other shocks would result in more profound restructuring of the industries.

The strength in

the city’s jobs numbers does not extend to all measures of the

economy. Real per capita personal income has grown by a meagre

2.6 percent per year over the past four years, a markedly poor

performance compared with the 4.5 percent average growth from

2003 through 2007 and the 3.6 percent average from 1996 through

2000 (another period of strong employment growth). The

underlying cause of the lackluster personal income growth is

weak wage and salary growth. Even as city job creation records

are being set, wages have been stagnant: the estimated overall

average wage in 2013 is virtually unchanged in real terms from

2010.

|

Average Wages and Salaries Since 2010 |

|||

|

|

2010 |

2013 |

Percent Change |

|

All Jobs |

$82,382

|

$82,752

|

0.4% |

|

Securities Sector |

376,605

|

342,529

|

-9.0% |

|

Other Finance and

Management |

134,474

|

135,821

|

1.0% |

|

All Other Private |

62,344

|

65,760

|

5.5% |

|

Government |

61,126

|

61,918

|

1.3% |

|

NOTE: In real 2013

dollars.

Independent Budget Office |

|||

Wall Street has

been the major factor behind recent weakness in average wage

growth in New York City, the mirror image of the role the sector

played in prior expansions. Real average wages (including

bonuses) in the securities sector have fallen 9.0 percent over

the last four years, and are languishing almost 22 percent below

their precrisis, 2007 peak. Other financial and management

sector wages have been nearly flat, as have government wages.

But even in the remaining, private nonfinancial portion of the

economy real wage growth has been relatively tepid: only 5.5

percent over three years.

If this seems

discordant with the city’s robust recovery and expansion, one

reason is that, while the city has far surpassed prerecession

levels of employment, it has not returned to prerecession levels

of utilization of those employed. Average weekly hours worked in

the city tumbled in the recession and since then have remained

persistently low. As a result, aggregate hours have grown much

more slowly than employment—and more in line with what we’ve

been seeing in the average wage numbers.

|

Private Sector

Employment and Hours Worked in New York City |

|||

|

Year |

January-October Averages |

||

|

Employment,

thousands |

Weekly Hours |

Aggregate Weekly Hours,

thousands |

|

|

2008 |

3,224.3

|

35.6

|

114,625

|

|

2013 |

3,394.9

|

34.5

|

117,060

|

|

Percent Change |

5.3% |

-3.0% |

2.1% |

|

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics

NOTE: Hours worked not available for government.

Independent Budget

Office |

|||

IBO projects a

modest uptick in average wage growth and with that, in per

capita personal income growth. The overall average real wage (in

2013 dollars) is expected to rise to about $93,300 in 2017,

enough to propel real per capita personal income growth of 3.5

percent per year over the 2014-2017 period.

|

Projected Average Wages and Changes in Employment by

Industry, 2013-2017 |

||||

|

|

Employment

Change, 2013-2017 |

Average Annual

Change |

Average Wage,

2013 |

Average Wage,

2017 |

|

Total |

272.5

|

1.7% |

$82,752

|

$93,263

|

|

Professional and Business Services |

73.4

|

2.8% |

104,637

|

119,469

|

|

Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services |

34.3

|

2.3% |

122,389

|

146,830

|

|

Administrative and Support Services |

34.2

|

3.9% |

52,302

|

54,226

|

|

Management of Companies and Enterprises |

3.2

|

1.2% |

184,641

|

207,940

|

|

Education and Health Care Services |

68.0

|

2.0% |

52,174

|

60,009

|

|

Health Care Services |

34.2

|

1.9% |

61,525

|

69,209

|

|

Social Assistance |

18.5

|

2.5% |

29,960

|

37,291

|

|

Education |

15.4

|

2.0% |

51,098

|

60,282

|

|

Leisure and Hospitality |

35.3

|

2.3% |

44,033

|

52,556

|

|

Retail Trade |

25.2

|

1.8% |

38,873

|

45,446

|

|

Construction |

18.1

|

3.6% |

78,696

|

87,529

|

|

Information |

15.1

|

2.1% |

119,581

|

126,831

|

|

Financial Activities |

12.0

|

0.7% |

207,030

|

226,497

|

|

Securities, Investments, and Related Activities |

8.6

|

1.3% |

342,529

|

363,490

|

|

Other Services |

10.0

|

1.4% |

49,866

|

57,193

|

|

Government |

8.4

|

0.4% |

61,918

|

70,386

|

|

Wholesale Trade |

7.5

|

1.3% |

90,710

|

108,094

|

|

Transportation and Utilities |

0.2

|

0.0% |

63,218

|

81,452

|

|

Manufacturing |

(0.6) |

-0.2% |

58,805

|

62,087

|

|

NOTE: Employment in thousands. Wages in real 2013

dollars.

Independent Budget Office |

||||

As has been the

pattern in recent years, IBO expects professional and business

services and education and health care services between them to

account for over half of the city’s total projected employment

growth. Next in terms of projected job growth are two industries

that are buoyed by the city’s vibrant tourism industry: leisure

and hospitality (which includes food services, accommodation,

and arts and entertainment) and retail trade. Construction,

which continued to slump for two years after the rest of the

city economy emerged from recession, is projected to be one of

the fastest growing sectors over the next four years, second

only to administrative and support services in terms of average

annual growth. In contrast, financial activities are projected,

along with government, transportation and utilities, and

manufacturing, to be among the slowest growing sectors.

In 2013 a little

over a quarter of the New York City’s payroll workers were in

industries with average industry real wages below $50,000, about

half were in industries with average wages between $50,000 and

$100,000, and a little less than a quarter were in industries

with average wages over $100,000. Job growth has generally been

strongest in the lower-wage industries, and continues to be so

in our forecast. Prior to the last recession, the industries

with the highest average wages also experienced by far the most

rapid growth in average wages during expansions (as well as the

steepest declines in wage growth during contractions). But

during the current expansion beginning in 2009, average wage

growth in the higher wage end of the distribution has markedly

weakened, and has been almost matched by wage growth at the

lower end. As the expansion continues, IBO projects that average

wage growth will rise more rapidly in the lower-wage industries

than in industries with higher wages.

|

Employment and

Wage Growth in Lower-, Medium-, and Higher- Wage

Industries |

||||||

|

|

Annual Employment Growth |

Annual Real Average Wage Growth |

||||

|

Lower Wage |

Medium Wage |

Higher Wage |

Lower Wage |

Medium Wage |

Higher Wage |

|

|

1993-2000 |

3.2% |

0.9% |

2.4% |

1.7% |

1.7% |

5.6% |

|

2000-2003 |

-0.1% |

-1.4% |

-3.8% |

1.0% |

0.9% |

-1.5% |

|

2003-2008 |

2.4% |

0.7% |

2.1% |

0.1% |

0.0% |

4.8% |

|

2008-2010 |

-0.9% |

-2.0% |

-5.9% |

-1.9% |

-0.3% |

-12.9% |

|

2010-2013 |

3.5% |

0.9% |

1.4% |

1.3% |

1.4% |

1.4% |

|

2013-2017f |

2.1% |

1.5% |

1.7% |

4.2% |

3.4% |

2.5% |

|

NOTE: Industries with average real wages under $50,000,

between $50,000 and $100,000, and over $100,000 as of

2013.

Independent Budget Office |

||||||

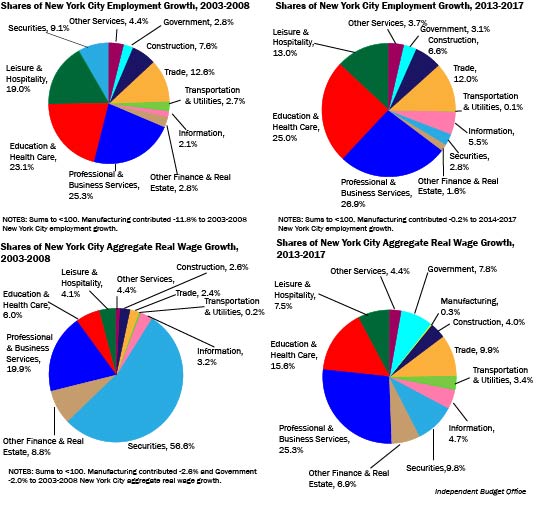

A major factor in

this change is a sharp decline in the contribution of the

securities industry to overall employment and—even more so—wage

growth. This change is not expected to be transient, but has

been ongoing since the recession began and will continue through

2017. Before the recession, from 2003 through 2008, securities

accounted for 9.1 percent of the employment growth in the

city—and a staggering 56.4 percent of the real aggregate wage

growth. From 2013 through 2017, by contrast, the securities

industry is expected to play a smaller but still significant

role in driving the local economy, providing just 2.8 percent of

the employment growth and 9.8 percent of the growth in aggregate

wages.

With slower wage

growth forecast for the securities industry, IBO expects the

shares of wage growth accounted for by other sectors of the

economy to get larger. For example, the professional and

business services industry’s share of wage growth is expected to

increase from 19.9 percent in the 2003 through 2008 period to

27.2 percent in 2013 through 2017; for education and health care

services the share is projected to grow from 6.0 percent to 15.6

percent.

Wall

Street Profits.

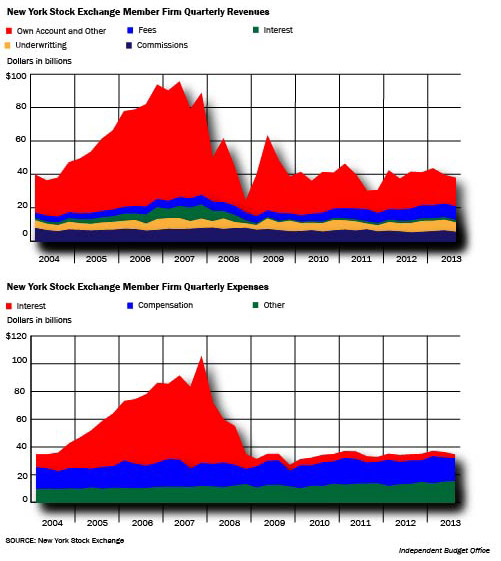

Wall Street

profits—as measured by the broker-dealer profits of member firms

of the New York Stock Exchange—have seen wild swings since the

onset of the financial crises. After losing $11.3 billion in

2007 and $42.6 billion in 2008, the firms had the largest

one-year profit in history in 2009, when the industry as a whole

made $61.4 billion. Profits stood at $23.9 billion in 2012, but

IBO expects profits to fall to $15.4 billion for 2013 as revenue

growth slows to 3.2 percent. Higher interest and compensation

costs in coming years will largely offset gains in revenues,

leaving profits on a relatively slow growth trajectory. IBO’s

forecast is for profits of $15.8 billion in 2014 and they are

expected to reach $17.2 billion by 2017.

This outlook for profits does not seem to reflect the forecast

of sluggish employment and wage growth in the city’s financial

sector. But in recent years broker-dealer profitability has not

been a function of strong revenues—on the contrary, revenues are

still running below half of their prerecession peak. Instead,

the broker-dealer bottom line has been rescued (for now) by much

reduced expenses, primarily resulting from extraordinarily low

interest costs. The latter mostly reflect the near-zero interest

rate policy pursued by the Federal Reserve.

New challenges

will confront Wall Street, and new pressures will be exerted on

industry employment and compensation, as interest rates head

back towards normal, while tightened regulatory constraints are

likely to preclude the kinds of extraordinary revenue gains seen

in the pre-2008 boom. The most recent regulatory change was the

adoption of the so-called Volcker rule, which is intended to

prevent institutions protected by federal deposit insurance from

engaging in proprietary trading. This has been an important

source of profits for banks—albeit with considerable risks. To

the extent banks are forced to shed their proprietary trading

operations this could constrain their revenues and profits. Of

course, if the trading units are spun off as new New York-based

firms, the potential negative effects on local employment,

output, and tax revenue may be reduced.

Real

Estate Markets.

Median sale prices of one- to-three family homes sold outside

Manhattan are up 5.4 percent this year, but prices still remain

about 15 percent below their 2007 peak. That peak may still not

be regained by the end of the forecast period. Conversely, the

coop-condo and residential rental markets have been very strong,

the former fueled by high-end demand from foreign buyers, the

latter by chronic shortages of available units.

There has been a

large year-over-year increase in commercial real estate sales

(and especially high value sales) in 2013, and aggregate

commercial market values have also climbed (up 6.3 percent),

although not as strongly as in recent years. However, average

Manhattan office rents have not budged much, edging up a modest

$1.60 per square foot. Projected growth in office rents is also

relatively subdued, only 2.9 percent per year over the next four

years—barely keeping pace with inflation.

The Unemployment Rate and Labor Force Participation. The city’s strong jobs growth has not produced as large a decline in the unemployment rate as one might expect. Indeed, New York City’s persistently high unemployment rate—still at 8.7 percent as of October 2013—remains a puzzle for those analyzing the city economy. In contrast to the new employment highs achieved in the city, payroll employment in the United States as a whole remains far below the prerecession peak. And yet the national unemployment rate has dropped more than a percentage point below the city’s rate. One potential explanation for the lower U.S. unemployment rate is the steeper decline in labor force participation at the national level.

IBO expects New York City’s unemployment rate to drop rapidly so that by 2016 it will have “caught up” to the declining national rate (6.3 percent). By 2017, the city rate is projected to be down to 5.2 percent—below the nation’s rate.

Risks to the Forecast.

As noted above, in the coming years New York City’s

financial institutions will come under increasing pressure from

rising interest costs and regulatory constraints on revenue

growth. The question is how far this could curtail—or even

reverse—the growth in our forecast. This depends first on how

tightly those pressures grip the financial sector, and second on

the resiliency of the city’s economy if employment and wages in

the financial sector contract. The key to resiliency is

retaining the strengths that have made New York City a magnet

for both millions of highly productive workers and tens of

millions of tourists. Those strengths could also be tested by

external risks related to the city’s position as a world

banking, trade, and tourism center.

|

IBO Versus Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget

Economic Forecasts |

||||||

|

|

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

|

National Economy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Real GDP Growth |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IBO |

2.8 |

1.7 |

2.8 |

3.4 |

2.9 |

2.9 |

|

OMB |

2.8 |

1.6 |

2.6 |

3.2 |

3.1 |

3.1 |

|

Inflation Rate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IBO |

2.1 |

1.4 |

1.8 |

2.2 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

|

OMB |

2.1 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.6 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

|

Personal Income Growth |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IBO |

4.2 |

2.9 |

6.0 |

7.0 |

6.2 |

5.0 |

|

OMB |

4.2 |

2.7 |

4.7 |

4.8 |

5.1 |

5.3 |

|

Unemployment Rate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IBO |

8.1 |

7.4 |

6.7 |

6.3 |

5.8 |

5.5 |

|

OMB |

8.1 |

7.5 |

7.1 |

6.5 |

6.1 |

5.7 |

|

10-Year Treasury Bond Rate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IBO |

1.8 |

2.4 |

3.3 |

4.2 |

5.0 |

4.9 |

|

OMB |

1.8 |

2.4 |

3.1 |

3.5 |

3.9 |

4.6 |

|

Federal Funds Rate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IBO |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.7 |

3.0 |

4.0 |

|

OMB |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

2.2 |

3.8 |

|

New York City Economy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nonfarm New Jobs, thousands |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IBO |

79.5 |

75.1 |

67.3 |

71.0 |

70.9 |

63.3 |

|

OMB |

80.0 |

73.0 |

48.0 |

47.0 |

51.0 |

50.0 |

|

Nonfarm Employment Growth |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IBO |

2.1 |

1.9 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

1.7 |

1.5 |

|

OMB |

2.1 |

1.9 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

|

Inflation Rate (CPI-U-NY) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IBO |

2.0 |

1.8 |

2.2 |

2.8 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

|

OMB |

2.0 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

1.8 |

2.1 |

2.0 |

|

Personal Income, $ billions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IBO |

479.2 |

497.8 |

527.3 |

562.4 |

598.6 |

627.7 |

|

OMB |

466.2 |

474.3 |

494.4 |

513.4 |

535.5 |

561.0 |

|

Personal Income Growth |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IBO |

3.7 |

3.9 |

5.9 |

6.6 |

6.4 |

4.9 |

|

OMB |

2.3 |

1.7 |

4.2 |

3.9 |

4.3 |

4.8 |

|

Manhattan Office Rents, $/sq.ft |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IBO |

66.7 |

68.3 |

69.6 |

72.1 |

74.6 |

76.7 |

|

OMB |

67.9 |

68.1 |

67.1 |

69.4 |

71.4 |

74.3 |

|

SOURCE: Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget

NOTES: Rates reflect year-over-year percentage changes

except for unemployment, 10-Year Treasury Bond Rate,

Federal Funds Rate, and Manhattan Office Rents. The

local price index for urban consumers (CPI-U-NY) covers

the New York/Northern New Jersey region. Personal income

is nominal.

For 2012, New York City personal income and growth rates

are estimated, pending BEA release.

Independent Budget Office |

||||||

Taxes

and Other Revenues

IBO’s forecast of

revenue from taxes and other sources including state and federal

aid totals $73.5 billion in fiscal year 2014 and $74.6 billion

in 2015, a relatively small increase of only 1.5 percent. But

growth in total revenue next year will be pulled down by the

presence of $1.1 billion in federal assistance for recovery from

Hurricane Sandy in the 2014 budget that is not included in

subsequent years. Without the Sandy aid, total revenue growth

for 2015 would be 3.1 percent.

While total

revenue growth is expected to be tepid from this year to next,

the tax revenue portion of that total is forecast to increase by

$2.6 billion (5.6 percent) to $48.3 billion. In contrast, the

city’s own nontax revenues are projected to fall by $319 million

(-5.0 percent) to $6.1 billion and noncity revenues in 2015 are

expected to be 5.4 percent lower than in 2014, thanks to the

drop in federal grants.

Following 2015,

total revenues are expected to grow in a more typical pattern,

increasing to $77.3 billion in 2016 and $80.5 billion by 2017.

Annual revenue growth will average 3.9 percent in these years,

driven by city taxes, which are forecast to increase at an

average annual rate of 5.2 percent. Growth in noncity revenue

sources is projected to average 2.0 percent annually in 2016 and

2017.

The first part of

this section presents IBO’s tax revenue forecast, followed by a

detailed discussion of each of the city’s major tax sources. It

concludes with a brief overview of the outlook for nontax

revenues.

Tax

Revenue Overview.

IBO’s forecast for

tax revenue in the current fiscal year is $45.7 billion, an

increase of 1.8 percent from 2013. For 2015, IBO projects faster

revenue growth of 5.6 percent to $48.3 billion. Tax revenue

growth in 2014 was slowed by a shift in the timing of capital

gains realizations by taxpayers seeking to lock in the lower

capital gains rates that expired at the end of December 2012,

thereby boosting personal income tax (PIT) revenues for 2013.

Much of the activity that was shifted to 2013 would have

normally occurred in 2014, and as a result PIT revenues are

expected to decline by $654 million (-7.1 percent) this year.

More than offsetting this decline are year-over-year gains from

two of the city’s business income taxes, the property

transaction taxes, and the sales tax. Growth from 2013 to 2014

is expected to be particularly strong in the real property

transfer tax (17.6 percent) and the mortgage recording tax (9.7

percent); although the real property transfer tax grew at a

similar pace last year, the mortgage recording tax increased at

the even faster rate of 38.3 percent.

Much of the

additional tax revenue forecast by IBO for 2015 is expected to

come from the personal income tax—an increase of $898 million

(10.6 percent)—thanks to steady employment growth and strong

personal income growth during calendar years 2014 and 2015, and

from the real property tax, where strong assessment growth,

particularly for multifamily housing and commercial property,

account for much of the $806 million increase (4.1 percent) in

revenue. IBO also expects a robust, 7.7 percent increase in the

business income taxes next year.

For 2016 and 2017,

IBO expects steady tax revenue growth to resume, averaging 5.2

percent annually. Tax revenues are forecast to reach $53.4

billion by 2017. Growth from the personal and business income

taxes, as well as the property tax and the transfer taxes is

expected to remain strong over the two years.

|

IBO Revenue Projections

Dollars in millions |

|||||

|

|

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

Average Change |

|

Tax Revenue |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Property |

$19,757

|

$20,563

|

$21,566

|

$22,613

|

4.6% |

|

Personal Income

|

8,514

|

9,413

|

9,997

|

10,502

|

7.2% |

|

General Sales |

6,468

|

6,775

|

7,096

|

7,394

|

4.6% |

|

General Corporation |

2,846

|

2,931

|

3,094

|

3,258

|

4.6% |

|

Unincorporated Business |

1,946

|

2,117

|

2,310

|

2,478

|

8.4% |

|

Banking Corporation |

1,202

|

1,409

|

1,466

|

1,542

|

8.7% |

|

Real Property Transfer |

1,277

|

1,283

|

1,399

|

1,532

|

6.3% |

|

Mortgage Recording |

814

|

847

|

934

|

990

|

6.7% |

|

Utility |

416

|

443

|

467

|

483

|

5.1% |

|

Hotel Occupancy |

493

|

490

|

517

|

544

|

3.4% |

|

Commercial Rent |

695

|

729

|

750

|

770

|

3.5% |

|

Cigarette |

59

|

58

|

56

|

55

|

-2.5% |

|

Other Taxes, Audits, and PEGs |

1,202

|

1,211

|

1,211

|

1,211

|

0.2% |

|

Total Taxes |

$45,688

|

$48,267

|

$50,862

|

$53,371

|

5.3% |

|

Other Revenue |

|

|

|

|

|

|

STaR Reimbursement |

$844

|

$880

|

$885

|

$889

|

1.7% |

|

Miscellaneous Revenues |

5,566

|

5,211

|

5,058

|

5,168

|

-2.4% |

|

Unrestricted Intergovernmental Aid |

-

|

-

|

-

|

- |

n/a |

|

Disallowances |

(15) |

(15) |

(15) |

(15) |

n/a |

|

Total Other

Revenue |

$6,395

|

$6,076

|

$5,928

|

$6,042

|

-1.9% |

|

Total City-Funded Revenue |

$52,084

|

$54,344

|

$56,790

|

$59,413

|

4.5% |

|

State Categorical Grants |

$11,754

|

$12,013

|

$12,355

|

$12,888

|

3.1% |

|

Federal Categorical Grants |

8,176

|

6,822

|

6,786

|

6,775

|

-6.1% |

|

Other Categorical Aid |

915

|

881

|

869

|

865

|

-1.9% |

|

Interfund Revenues |

534

|

514

|

514

|

514

|

-1.3% |

|

TOTAL Revenues |

$73,463

|

$74,574

|

$77,313

|

$80,455

|

3.1% |

|

NOTES: Estimates exclude intracity revenues. Figures may

not add due to rounding.

Independent

Budget Office |

|||||

The shift of income tax revenue from 2014 to 2013 is a critical

explanation, but the expectation that tax revenue growth will be

slower this year and then accelerate in 2015 is also generally

consistent with IBO’s economic forecast. Strong employment gains

during calendar year 2013 are expected to be followed by a

smaller increase in 2014, but then somewhat larger increases is

2015 and 2016. This same pattern is broadly followed by the tax

revenue forecast.

One thing not found in IBO’s forecast is a projection for double-digit tax revenue growth, something that did occur each year from 2004 through 2007. In the near-term, continued difficulties in the securities industry, including lower aggregate earnings, declines in employment, and an expectation of lower profits will mean less tax revenue generated from Wall Street. IBO expects growth in the securities sector—along with growth in city tax revenues—to remain relatively modest compared with growth during the pre-2008 expansion or even the more recent years of slow recovery. Indeed, the projected annual average growth in total tax revenue over the three years after 2014 is 5.3 percent, significantly lower than the 7.3 percent average over the most recent three-year period after 2010.

Compared with the

city’s revenue forecast when the 2014 budget was adopted last

spring, IBO’s new forecast is $1.2 billion (2.7 percent) higher

for this year and our outlook for 2015 is $1.3 billion (2.8

percent) above the adopted budget estimate. While the strength

in 2014 collections is not entirely surprising—IBO’s estimates

last spring indicated that the city was underestimating 2014

revenues by over $600 million—the local labor market and the

market for real estate have proved to be even stronger than

expected last spring, prompting large upward revisions in our

forecast of the personal income tax, the general corporation

tax, and the real property transfer tax. But in this latest

round of forecasts, IBO has made only modest revisions to our

projections from last spring for 2015 through 2017—in our

forecast of total revenues declined slightly for each year.

IBO’s latest tax

revenue forecast for 2014 is $683 million, or 1.5 percent,

higher than the OMB forecast that accompanied the November 2013

financial plan update. Beginning with 2015, the gap between the

two forecasts grows each year from $1.3 million next year to

$2.5 billion in 2017, but the differences never exceed 1.3

percent of total tax revenues.

Real

Property Tax.

IBO projects that

property tax revenues will grow from $19.8 billion in 2014 to

$20.6 billion in 2015, a 4.1 percent increase. We expect

property tax revenue to grow at an average annual rate of 4.6

percent over the financial plan period.

IBO’s revenue

forecast for 2014 includes $50 million in nonrecurring revenue

from retroactive changes to the coop and condo abatement

program. In January 2013, the state legislature enacted changes

to the abatement program, retroactive to the July 1, 2012 start

of the 2013 fiscal year. The Department of Finance reflected

these changes on 2014 property tax bills beginning in June 2013.

Additionally, the

state is requiring recipients of the School Tax Relief program

(STAR) to register with the state; previously administration of

the program was

handled locally.

City homeowners who receive STAR benefits enjoy a partial

property tax exemption of about $300 a year and the state

reimburses the city for the foregone taxes. The registration

requirement will not affect city tax collections because the

taxes will either be paid by taxpayers or reimbursed by the

state; however, low registration rates (about 60 percent of

recipients registered by December 9, 2013) suggest that city

residents could lose out on roughly $68 million in state

property tax relief.

Background.

The amount of tax owed on real estate in New York City depends

on the type of property, its value for tax purposes (as

calculated by the city’s Department of Finance from estimated

market value), and the applicable tax rate.2 Under

property tax law, there are four tax classes: Class 1,

consisting of one-, two-, and three-family homes; Class 2,

composed of apartment buildings, including cooperatives and

condominiums; Class 3, made up of the real property of utility

companies; and Class 4, comprising all other commercial and

industrial property.

The method of

assessing properties and recognizing market value appreciation

differs by tax class, so each class can have its own assessment

ratio (the share of market value actually subject to tax) and

tax rate. Because of differences in class assessment ratios, the

share of assessed value borne by each class is not proportional

to its share of market value. Class 1 accounts for a much

smaller share of total assessed value than its share of market

value—9.5 percent of assessed value on the 2014 roll compared

with 46.1 percent of the department’s estimate of total market

value in the city. The other classes, especially Classes 3 and

4, bear a disproportionately large share of the property tax

burden because their shares of assessed value are much bigger

than their shares of market value.

Coop and Condo

Abatement.

The coop and condo

abatement provides a reduction in property taxes for owners of

cooperative and condominium units. After having expired on June

30, 2012, the abatement was renewed with significant changes in

January 2013, retroactive to July 1, 2012. The abatement

program’s eligibility criteria were revised to restrict the

abatement to apartments used as primary residences. The renewed

abatement also has a higher percentage of taxes abated for most

owners who remained eligible. IBO has documented shortcomings of

the original abatement: it was supposed to be a temporary first

step toward equalizing tax burdens on apartment owners and

homeowners; it does not address disparities among apartment

owners; and it is inefficient because the abatement provides

more relief than needed to some owners and less to others. Our

analysis

of the most recent changes found that these shortcomings remain.

Due to the retroactive nature of the changes, the Department of

Finance is recouping coop and condo benefits granted in 2013 to

owners whose apartments are not their primary residences and

therefore no longer eligible for the tax break. Although the

abatement expired at the start of 2013, the finance department,

assuming a retroactive extension would be enacted, decided to

leave the abatement unchanged on 2013 property tax bills.

Because the abatement was instead revised to reduce benefits for

nonresident owners for 2013, the department is seeking to recoup

those benefits by adding to property tax bills in 2014. Rather

than adding the charge as a lump sum at the beginning of the

year, the finance department has spread out the additional tax

for 2013 across all the bills for 2014.

According to finance department tax billing data, roughly $67

million in abatement benefits for 2013 will be billed in 2014.

The city has already collected $12 million in 2013 (from bills

mailed in June and paid before July 1, 2013) and another $27

million so far this year. IBO expects that $50 million will be

collected this year (this estimate allows for some nonpayment).

While the city has not yet reflected this additional 2014

revenue in the financial plan, IBO’s estimate of 2014 property

tax revenue has increased to reflect the revenue we expect the

city to recoup over the year.

Finance department

data show that the modified abatement will cost the city about

$400 million in foregone property tax revenue in 2014, which is

the amount reflected in the IBO forecast for this year. IBO

expects the cost to decrease to $370 million in 2015 as the

changes are fully phased in. Our estimates are significantly

lower than what the Mayor’s financial plan assumes the program

will cost the city by about $50 million in 2014 and $80 million

in 2015. Although the abatement was only extended through 2015,

our forecast assumes it is continued in 2016 and 2017 without

further changes.

Assessment Roll

for 2015.

IBO projects that

when the tentative assessment roll for 2015 is released in

January 2014, it will report 5.2 percent growth in market values

in the city. Assessed value for tax purposes is forecast to grow

by 4.6 percent in 2015.

Class 1: The

aggregate market value of Class 1 properties is expected to grow

4.2 percent in 2015. This growth is stronger than in the past

six years (four of which saw declining market value), although

Class 1 market value in 2015 is projected to remain below the

peak recorded in 2008. The growth reflects an increase in the

median sale price for Class 1 homes in calendar year 2013. The

median sale price of one-, two- and three-family homes outside

Manhattan in the first three quarters of 2013 was $465,000

compared with a median of $440,000 in the first three quarters

of 2012.

IBO projects

assessed value for tax purposes in 2015 will increase by 3.0

percent over 2014. In Class 1, the assessed value of a property

moves toward a target of 6.0 percent of market value, with

assessment increases capped at 6.0 percent a year or 20 percent

over five years. If a parcel is assessed at less than 6 percent

of market value, its assessed value will grow each year until it

hits the target ratio of 6.0 percent of market value or it

reaches the cap on annual assessment increases—even if the

market value stays flat or declines compared with the prior

year. When the housing market was strong, the median ratio for

one-family homes outside Manhattan declined, from 5.4 percent in

2004 to a low of 3.7 percent in 2008, well below the 6 percent

target. More recently, the median assessment ratio has

increased, rising from 4.0 percent in 2009 to 5.4 percent in

2014.

Class 2 and Class

4: IBO projects that on the final roll for 2015, aggregate

market value for all properties in Class 2 will total $215.1

billion, a 6.2 percent increase over 2014. The Class 2 increase

is higher than in recent years, stemming from strong projected

growth in market values across all property types in the class.

Class 4 aggregate market value is expected to reach $248.8

billion, a 6.3 percent increase over 2014. This growth is

slightly slower than in recent years; annual market value

increases in Class 4 averaged 7.3 percent from 2011 through

2014.

Aggregate assessed value for tax purposes for Class 2 is

expected to be $60.9 billion, 3.4 percent higher than 2014, and

$89.2 billion for Class 4, a year-over-year increase of 5.7

percent. This projected growth in 2015 is lower than annual

growth for Classes 2 and 4 from 2006 through 2014, which

averaged 5.4 percent and 6.6 percent, respectively.

This stable growth

in assessed value for tax purposes is due in part to the method

for translating market value changes into assessed value for tax

purposes. Increases and—in many cases—decreases in parcels’

market values are phased in over five years. The assessed value

changes from the preceding four years that have yet to be

recognized on the tax roll are called the pipeline. Strong

growth in assessed value in recent years, especially in Class 4,

has replenished the pipeline, which had begun to shrink due to

slow growth in the preceding years. IBO projects that the

pipeline will reach $16.5 billion in 2015, up sharply from $6.6

billion in 2011.

Outlook for Market and Assessed Values in 2016 and 2017.

For 2016, IBO forecasts an increase in aggregate market value of

4.7 percent. Growth in market value is projected at 3.2 percent

in Class 1, 5.8 percent in Class 2, and 6.2 percent Class 4.

Class 1 growth slows a bit in 2017, forecast at 2.5 percent,

while Class 2 and Class 4 are projected to grow by 5.9 percent

and 6.2 percent, respectively.

IBO projects that aggregate assessed value for tax purposes will

grow 5.1 percent in 2016 and 5.0 percent in 2017, slightly

faster than in 2015. Class 1 assessed value for tax purposes is

expected to grow by 2.8 percent in both years. With the pipeline

replenished, growth of assessed value for tax purposes in both

Classes 2 and 4 is strong through 2017, especially in Class 4.

Assessed value for tax purposes in Class 2 will grow 3.2 percent

in 2016 and 3.7 percent in 2017. The Class 2 pipeline, estimated

at $5.3 billion following the 2014 final roll, is expected to

grow to $6.3 billion by 2017. With an even larger pipeline,

Class 4 growth in assessed value for tax purposes will be even

stronger, averaging 6.5 percent a year through 2017. IBO

estimates that the Class 4 pipeline was $9.4 billion after the

2014 roll was finalized, and will grow to $11.7 billion by 2017.

Revenue Outlook.

The

Department of Finance is responsible for finalizing the

assessment roll, while the actual property tax levy is

determined by the City Council when it sets the tax rates for

each class. IBO’s baseline property tax revenue forecast and the

Bloomberg Administration’s forecast both assume that the average

tax rate during the forecast period will remain at 12.28

percent, the rate set by the City Council in December 2008 when

the Council enacted the Mayor’s proposal to rescind a

short-lived 7.0 percent rate reduction.

The amount of

property tax revenue in a fiscal year is determined not only by

the levy, but also by the delinquency rate, abatements granted,

refunds for disputed assessments, and collections from prior

years. Taking these other factors into account, IBO projects

that property tax revenue for 2014 will total $19.8 billion, 5.4

percent higher than in 2013. For 2015, IBO forecasts property

tax revenue of $20.6 billion. From 2015 through 2017, revenue

growth is projected to average 4.9 percent a year, reaching

$22.6 billion by the last year of the forecast period. This

projected revenue growth is slower than the 6.3 percent average

annual growth seen from 2007 (before the most recent property

tax rate decrease and increase) through 2013.

IBO’s property tax

revenue forecast is $147 million above OMB’s for 2014, stemming

primarily from differences in estimating the savings from

changes to the coop and condo abatement program and estimates of

prior year collections. In 2015 through 2017, IBO forecasts

somewhat stronger market value growth than OMB, and our revenue

forecast is respectively $236 million, $308 million, and $587

million above OMB’s.

Real

Estate Transfer Taxes.

Revenues from the real property transfer tax (RPTT) and the

mortgage recording tax (MRT)—collectively referred to as the

transfer taxes—have rebounded strongly since 2010, when in the

wake of the financial crisis they bottomed out

at $981 million (a 70.2

percent drop from their 2007 peak). For 2014, IBO

forecasts a total of $2.1 billion in revenues from the two

taxes, growing to $2.5 billion in 2017—still about 25 percent

below the 2007 peak of $3.3 billion.

Because the RPTT

and MRT are based on a certain percentage of real property sales

and mortgages, respectively, the recovery of real estate markets

since the recession have boosted transfer tax revenue. Taxable

sales of residential properties soared to $12.5 billion during

the first quarter of this fiscal year, the highest level since

the July-September 2007 quarter. The increase in sales activity

occurred in all five boroughs, although Manhattan continued to

account for the majority of sales value with 59.7 percent in the

quarter.

After a spike in

commercial real estate sales at the end of calendar year 2012,

when buyers and sellers rushed to complete transactions in

anticipation of higher capital gains tax rates taking effect in

January 2013, taxable commercial sales fell by over 60 percent

to $5.9 billion in the April to June quarter of 2013. Sales then

rebounded in the July to September quarter (the first quarter of

the 2014 fiscal year), to $10.4 billion. There have been 41

taxable commercial sales valued at more than $100 million in the

first five months of this fiscal year compared with 24 during

the same period of 2013. Five of these sales were valued at over

$500 million compared with just two during the same period last

year. The largest transaction so far this year has been the $1.3

billion sale of 650 Madison Avenue, recorded in October—the

highest-value taxable transaction in the city since December

2010.

In response to the

strength of collections so far this fiscal year, IBO has raised

its 2014 forecast of RPTT revenue by $169 million over our May

2013 projection, to slightly under $1.3 billion—on a

year-over-year basis, revenue is now expected to grow by 17.6

percent in 2014. Our forecast for 2015 through 2017 is

essentially unchanged since May, with growth moderating to an

annual average of 6.3 percent. By 2017, RPTT revenues are

forecast to be $1.5 billion, roughly 90 percent of their 2007

peak.

The MRT does not

track the value of real estate sales as closely as does the RPTT

because not all sales involve a mortgage and new taxable

mortgages need not involve a sale. All-cash sales are common in

the city’s luxury housing market, both among U.S. residents and

the foreign buyers who account for a significant share of

high-end residential purchases. The latter are in many cases not

able to obtain financing locally and, if they borrow overseas,

there is no mortgage recorded in the city and therefore no MRT

liability. In addition to mortgage activity related to property

purchases, the MRT can be triggered in some mortgage

refinancings–it is levied on the portion that involves new money

(“cash out”) and also in cases where there is a new lender and

the original lender does not assign the note. MRT collections in

recent years have been boosted by the large volume of

refinancing activity that historically low mortgage interest

rates have induced.

As we did with our

forecast for RPPT collections, IBO has increased its forecast

for 2014 MRT revenue since last spring. MRT revenue this year is

now expected to be $814 million, $72 million (9.7 percent) over

2013 revenue. Even though mortgage rates remain at very low

rates by historic standards, credit standards are more stringent

than during the real estate boom of the previous decade, and it

is likely that most mortgage holders who would benefit from

refinancing and are able to access credit have already

refinanced. The Mortgage Bankers Association has also reported a

decline in refinancing activity in recent months. For these

reasons, IBO forecasts slower MRT growth in 2015 of 4.1 percent,

with revenues of $847 million. After 2015, annual average growth

of 8.1 percent is projected, with MRT collections reaching $990

million in 2017—still 37 percent below the peak a decade

earlier.

Differences between IBO’s and OMB’s forecasts of the transfer

taxes are relatively small. IBO’s projections for the RPTT are

slightly above those of OMB in each year—by 1.3 percent for the

entire forecast period. IBO’s mortgage recording tax projections

are slightly below OMB’s in 2014 and 2017, and higher in 2015

and 2016. For the entire 2014-2017 period, our MRT forecast is

0.9 percent above OMB’s.

Personal

Income Tax.

In contrast to most of New York City’s other major sources of

tax revenue, net collections (gross collections minus refunds)

from the personal income tax (PIT) are expected to decline this

year. IBO forecasts $8.5 billion of PIT revenue this year, $654

million less than what was generated in 2013. The drop in

revenue is the consequence of federal fiscal policy rather than

declines in the income and/or employment of city residents. In

anticipation of expected increases in federal income tax rates,

particularly rates on capital gains income, many taxpayers

shifted capital gains and salary bonuses from calendar year 2013

to 2012, boosting fiscal year 2013 PIT receipts at the expense

of receipts in 2014. As a result, PIT revenue growth is expected

to be uneven, with a 15.3 percent increase in 2013 followed by a

projected 7.1 percent decline this year and then a projected

10.6 percent increase in 2015.

The shift of capital gains realizations into

2013 swelled estimated payments, which are made by taxpayers who

are self-employed or anticipate realizing capital gains from the

sale of financial and property assets, along with those filing

for extensions to delay the deadline for final returns past

April 15th. IBO’s projection of a 26.9 percent

decline in estimated payments in 2014 is the major reason for

our forecast of a decrease in total PIT revenue. Another

contributing factor is an expected 8.9 percent increase in

refunds this year.

In contrast, withholding payments—the single largest component

of PIT receipts—are expected to show modest growth in 2014.

Fueled by job growth over the past year, year-to-date (through

November) withholdings are up 4.5 percent over the same period

in 2013. With a decline in Wall Street profitability expected

for calendar year 2013, however, we expect bonus compensation

from securities firms to be less than bonuses paid out of

profits in calendar year 2012. As a result, withholdings during

the all-important December through March bonus season will be

substantially less than withholdings in the same period in

2013.Consequently, withholding growth for the year as a whole

will be constrained to a relatively modest 3.2 percent.

IBO’s 2015 PIT

forecast is $9.4 billion—10.6 percent higher than we project for

2014. Withholding growth is expected to remain moderate,

reflecting slightly slower employment gains in calendar year

2014 relative to the two previous years. However, PIT growth

will be fueled by a projected 32.1 increase in estimated

payments as capital gains realizations rebound.

With IBO expecting

personal income growth to peak in calendar years 2015 and 2016,

we project that PIT revenues will increase at an annual average

rate of 5.6 percent in 2016 and 2017—faster than the annual

average rate of 1.3 percent in 2014 and 2015. PIT revenue is

forecast to reach $10.5 billion by 2017, 20.0 percent higher

than the previous revenue peak in 2008, before the Great

Recession.

IBO projects

faster city income and employment growth in its economic outlook

than does OMB throughout the forecast period, and as a result

IBO’s personal income tax forecast exceeds OMB’s each year

through 2017, with the difference between the two forecasts

growing over time. For the current year, our forecast is $190

million (2.3 percent) above OMB’s and for 2015 the difference

rises to $368 million (4.1 percent). Combined 2016 and 2017

revenue is 7.2 percent higher in the IBO forecast than in OMB’s.

Business Income

Taxes.

After stronger than anticipated revenue growth in 2013 (9.2

percent) from the city’s three business income taxes, combined

collections to date in 2014 (through October) are essentially

flat (-0.4 percent) compared with the same period a year before.

For the remainder of 2014, IBO forecasts only slightly faster

growth, resulting in a very modest increase of 2.3 percent in

business income tax revenue for the year as a whole. The

expected change in revenue varies among the three taxes. In

2014, collections of the general corporation tax (GCT) and the

unincorporated business tax (UBT) are projected to exceed 2013

revenues by 5.7 percent and 7.6 percent, respectively. Banking

corporation tax (BCT) revenues, however, are forecast to decline

11.5 percent this year. For 2015, IBO expects more robust growth

of 7.7 percent in the combined business income taxes, with all

three taxes contributing to the increase.

IBO’s general

corporation tax forecast is $2.8 billion for 2014—5.7 percent

($154 million) greater than revenue in 2013. Through October,

GCT collections for 2014 are up $72 million (15.3 percent) over

the same period last year. Data on current-year payments from

large taxpayers (those with payments of $1 million or more)

indicate that much of the growth so far has come from firms in

finance and insurance (up 64.9 percent) and manufacturers (up

135.8 percent). In contrast, collections from large information

firms were down 60.8 percent. GCT collections this year are

being boosted by the $23.9 billion in profits Wall Street firms

enjoyed in calendar year 2012—the third highest level on record.

Relatively strong Wall Street profits in calendar year

2013—$13.5 billion through the third quarter of the year—will

also bolster GCT revenue in 2014 and 2015. But securities firms’

interest and compensation expenses are projected to increase

starting late in calendar year 2014, reducing Wall Street

profits and slowing the increase in GCT revenue to 3.0 percent

in fiscal year 2015. For 2016 and 2017, IBO projects that GCT

collections will grow at an average annual rate of 5.4 percent.

UBT revenue

growth is expected to exceed that of the other two business

taxes over the entire forecast period, due in large part to

robust growth in the professional and business services

industry, which added 44,000 jobs from 2010 through 2012 and is

expected to add another 18,500 jobs in calendar year 2013. For

2014, IBO forecasts $1.9 billion in UBT revenue—$138 million

(7.6 percent) greater than 2013 collections—which would bring

UBT collections to $94 million above their 2008 prerecession

peak. September and October collections are up $41 million (11.9

percent), compared with the same period last year, but growth is

expected to slow in the remainder of the fiscal year. With both

the local and national economies gaining momentum in calendar

year 2014, IBO anticipates even faster UBT revenue growth next

year and beyond: 8.8 percent in 2015 and an average annual rate

of 8.2 percent in 2016 and 2017, when UBT revenue reaches $2.5

billion.

The bank tax is

the city’s most volatile major source of revenue, with strong

revenue growth in one year often followed by a steep decline the

following year. The bank tax’s volatility is primarily due to

very large fluctuations in refunds resulting from overpayments

of estimated liabilities made throughout the fiscal

year—overpayments often affected by the timing of deductions for

net operating losses. Through October, BCT collections for the

current fiscal year are $118 million (28.4 percent) less than

during the same period last year, a revenue decline completely

offsetting the combined growth of GCT and UBT revenue so far

this year. For 2014 as a whole, IBO forecasts that BCT revenue

will fall by 11.5 percent to $1.2 billion, and then rebound,

increasing 17.2 percent to reach $1.4 billion in 2015. Following

the sharp rise in 2015 collections, IBO expects BCT growth in

2016 and 2017 to average a more moderate 4.6 percent a year.

There are

several reasons to expect BCT revenue growth to slow in the

coming years. Rising interest rates will increase to cost of

obtaining funds and thereby take a toll on bank profits. Many of

the recent settlements between large banks and the U.S.

government over practices leading up to the 2008 financial

crisis include payments by the banks. To the extent these

payments are tax deductible, they lower banks’ taxable income,

thereby shrinking BCT collections. Instituting Dodd-Frank

regulations, including the just-adopted Volcker Rule, is also

expected to take a toll on BCT collections by limiting some

activities by banks, including highly lucrative (and potentially

risky) proprietary trading. The still high standards for issuing

small business loans will also limit potential bank profits.

IBO’s forecast

for the combined business income tax revenue is $218 million

(3.8 percent) higher than OMB’s in the current year—$231 million

higher for GCT, $101 million lower for BCT and $88 million

higher for UBT. For 2015, IBO’s forecast is a total of $467

million above OMB’s—$174 million higher for GCT, $214 million

higher for UBT, and $79 million higher BCT. The difference

between the two forecasts grows each year and reaches $824

million in 2017, reflecting IBO’s forecast of faster employment

and productivity growth.

General Sales Tax.

IBO

forecasts relatively steady growth in general sales tax revenue

for 2014 and subsequent years. For the current year, revenue is

expected to total $6.5 billion, a 5.5 percent increase over the

prior year—matching the growth rate in 2013. For 2015, IBO

projects $6.8 billion in revenue, a gain of 4.7 percent over

2014. In the following two years the sales tax is expected to

grow at an annual average rate of 4.5 percent, to $7.4 billion

in 2017.