September 2018

More Schools Eligible, Less Aid Available:

Federal Support Shrinks for City

Schools With Many Low-Income Students

PDF version available here.

Summary

Title I is the largest source of federal aid for elementary and secondary schools, providing school districts across the country with funding for after-school academic support, bilingual programs, health services, parent involvement efforts, and other programs for students from low-income families. In school year 2016-2017, federal officials allocated more than $14 billion in Title I funds to over 69,000 schools nationwide, with Title I-A funding making up most of the allocation. But even as more of New York City’s schools qualify for Title I-A the amount of funding available to the city has been decreasing.

The shrinking aid to the city stems from several fiscal and demographic factors. Federal Title I-A allocations to states have been relatively flat (the money flows from Washington to the states where it is then divided among school districts), although the number of eligible students nationwide has been growing. While the number of eligible students in New York State has grown over the years 2006 through 2017, it has lagged the rise in most other states, resulting in a decrease in funds to Albany. The distribution of funds from states to school districts also depends upon the poverty rate of individual schools. New York City has had a decline in the number of eligible children over the 2006-2017 period, even as the number of city schools eligible for Title I-A has climbed during those years. With fewer funds going to more schools, allocations to individual schools are shrinking.

In this report, IBO looks at the history of Title I-A and New York City schools’ eligibility and allocations. Among our findings:

- The number of low-income children eligible for Title I-A funding nationwide grew by about 28 percent from calendar year 2006 through 2017. Over that same period, federal spending on the program grew by just 17 percent.

- In school year 2005-2006, New York City received just over $1 billion in Title I-A funds (in 2017 dollars). By school year 2016-2017, the city’s allocation had shrunk to just under $650 million, a nearly 38 percent decline.

- From school year 2005-2006 through 2016-2017, the number of Title I-A eligible schools in the city increased from 1,058 to 1,265, a rise of nearly 20 percent.

If recent funding and demographic trends continue it is likely that New York City and other school districts across the country will need to either find efficiencies in the delivery of their Title I-A funded programs, fill shortfalls with local funds, or cut back on services.

Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) is the largest federal program that supports elementary and secondary education across the United States. In school year 2016-2017, over $14 billion was allocated to the nation’s school districts to provide students from low-income families supplemental services to enhance their educational experiences and improve outcomes. Nationwide, Title I provides support for over 69,000 eligible schools.1 New York State alone receives over $1 billion annually to provide Title I services. A majority of this funding is designated for Title I, Part A (Title I-A), which is the largest component of Title I, providing federal support for improving basic programs operated by state and local educational agencies. It covers a broad range of services for low-income students including: after-school academic support, education software, guidance and college and career counseling, bilingual services, books for libraries and classrooms, funding for parental involvement, and student health services.

In 2016-2017, New York City students benefited from $648.7 million of Title I-A funding, 2.8 percent of that year’s budget for the New York City Department of Education (DOE). The share of Title I-A funding in DOE’s budget has been decreasing in recent years. Federal Title I-A funding comes to the city by way of Albany. From state fiscal year 2006 through 2017, New York City saw a $140.4 million (17.8 percent) decline in its Title I-A allocation. (Adjusted for inflation, the decline was a much steeper 37.5 percent.) Simultaneously, more city schools were qualifying for Title I-A funding while few were losing eligibility. Thus, city officials were forced to spread a shrinking pot of funding across more schools. With federal allocations remaining close to stagnant year to year nationwide, schools have felt the impact of Title I funding shortfalls.

In this report, the Independent Budget Office explores what factors have contributed to the declining Title I-A funding. Specifically, we look to answer:

- How have changes in the number of Title I-A eligible students nationally and in New York State affected New York City’s share of Title I funds?

- How many New York City schools are designated as Title I-A eligible, and what impact does this have on the amount of funding each school receives?

- How has the distribution in Title I-A eligibility and funding across schools changed?

Our analysis is focused on New York City traditional public schools in districts 1 through 32, charter schools within New York City, and nonpublic school students who receive Title I-A services from the DOE. The analysis uses data from school years 2005-2006 through 2016-2017.

History of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act and Title I-A

The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), signed into law in April 1965, was the education cornerstone of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society policies. Over the following decades, ESEA and its components were amended and reauthorized to fill gaps in the original law, and to reflect the changing viewpoints on how big a role the federal government should have in educating students. Specifically, Part A of Title I of ESEA, has also undergone numerous amendments. These changes were made in order to address ambiguities in the statutory language, guide states in implementing acceptable program designs, and add requirements to make it clear that federal aid is to supplement rather than simply replace state and local funds.2

Title I-A was extensively modified under the 2001 reauthorization as part of the No Child Left Behind legislation. Under that act, school districts and states were held to a higher standard of accountability by linking funding to student performance. It was amended further during the most recent authorization of ESEA: the Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015 (referred to as ESSA). While funding formulas remained intact from No Child Left Behind and accountability remains a key component in the law, ESSA was written to increase states’ role in oversight and discretion in how the funds are used.

More recently, Congress approved legislation that President Trump signed, effectively repealing Obama-era ESSA accountability and teacher-preparation regulations. Congress allocated $14.9 billion in Title I-A funding for the 2017 federal fiscal year, a $500 million increase from 2016.

Title I-A Funding: From the U.S. Department Of Education to the States

When first enacted, the purpose of Title I-A was to provide local educational agencies serving areas with concentrations of children from low-income families with financial assistance to expand and improve their educational programs3. A little over a half century later, this purpose is still embodied in Title I of ESSA, which seeks to improve educational programs in order to provide all children opportunities to receive a fair, equitable, and high-quality education, and to close gaps in educational achievement.4

From 1965 through 1994, funding streams were gradually added alongside the original formula in order to direct additional aid to school districts; by 1994 there were four separate formula grants used to distribute funds. While the grant formulas differ, each one is based on census data on the number of school age children (defined as ages 5 to 17) from low-income families in a school district. Low-income families are measured using three different metrics: the number and concentration of students living below the poverty level, the number of children in foster care, and the number of children receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Children who qualify for Title I-A assistance under any of these criteria are known as “formula” or “federally eligible” children. In order to determine the number of children living in poverty, the U.S. Department of Education relies on the Census Bureau’s Small Area Income Poverty Estimates (SAIPE) program. This program provides annual estimates of income and poverty statistics for all school districts, counties, and states in order to assist in the administration of federal programs and allocation of federal funds to local jurisdictions. More specifically, the SAIPE program produces annual estimates of total population, the number of children ages 5 to 17, and the number of related children ages 5 to 17 in families in poverty.5

Basic Grants.The Basic Grant formula is Title I, Part A’s original and largest funding stream. Eligibility for a Basic Grant was, and remains, broad; districts are eligible to receive a Basic Grant if there are at least 10 eligible students and the number of eligible students is more than 2.0 percent of the district’s total enrollment. Under Basic Grants, the same amount of funding for each eligible student is provided to every district within a state.

Concentration Grants. These grants were introduced in the Education Amendments of 1978. Similar to Basic Grants, Concentration Grants send the same amount per eligible child to each district within a state. Unlike Basic Grants, Concentration Grants are provided only to districts that have more than 6,500 eligible students or to districts in which the share of students who are eligible is at least 15.0 percent of the district’s school-age population.

Targeted Grants. Although Targeted Grants were first authorized in the 1994 reauthorization of ESEA, known as the Improving America’s Schools Act, they were not funded until 2002.6 To receive a Targeted Grant, a district must have at least 10 eligible students and eligible students must be at least 5.0 percent of the district’s total enrollment. Targeted Grants are intended to provide additional funding beyond the Basic Grant for districts with a larger share of eligible students than necessary to qualify for Basic Grants.

Education Finance Incentive Grants These grants were also not authorized until 1994, nor funded until 2002. Education Finance Incentive Grants are distributed to districts where there are at least 10 formula children who make up at least 5.0 percent of the school-age population. These grants are distributed based on the degree to which education expenditures among districts within the state are equalized, as well as a state’s effort to provide financial support for education, with effort based on a state’s education spending relative to its wealth.

In addition to grant formulas, a district’s ultimate Title I-A funding is also determined by several other factors. There is a statutory minimum state allocation requirement that provides funding above the grant formula amounts to states with few formula children, as well as a hold-harmless provision that limits the amount of funds a district can lose from one year to the next. Additionally, ESEA also adjusts grants on a per pupil basis to account for differences in the cost of education across states and there is a state set-aside amount. This set-aside provides resources for states to fund administrative duties such as data collection and oversight, and also enables states to support school districts in areas such as technical assistance.7

Although Congress authorizes the maximum amount of dollars to be allocated to states, funding is capped at the level of appropriation determined by Congress. To date, Congress has fully funded Title I only once, in 1965, the year it was first enacted.8 In other years, grants to each district were reduced proportionally to account for the difference between the level of funding authorized by Congress, and the funding that was actually appropriated.

Title I-A Funding: From States to Districts, Districts to Schools

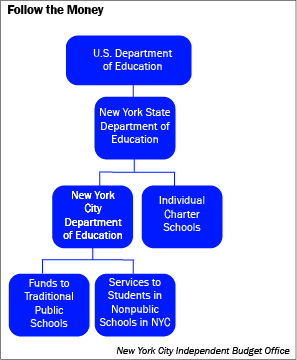

Once funding is allocated to each state by the U.S. Department of Education, states then distribute funds to each qualified school district based on the same criteria used in the initial allocations to states: the number of children ages 5 to 17 living in poverty, the number of children in foster care, and the number of children receiving TANF, again derived from SAIPE census data. The eligible population includes students in traditional public schools, charter schools, private schools, and religious schools.

For school districts that contain two or more counties, such as New York City, ESEA requires that each county be treated as if it were a separate school district for the purposes of calculating grants. (All five New York City counties or boroughs qualify under the criteria for all four of the formula grants.) The total grant amount for each county is distributed to the school district—in this case, the New York City Department of Education.9 The Department of Education then distributes a share of its total grant to eligible schools in each county, or borough, based on the county’s share of the population.10

Public charter schools are considered separate school districts from the district in which they are located. Therefore each charter school, including individual charter schools within the same network, receives Title I-A funding directly from the state if they are eligible rather than from their public school district.

Nonpublic school students can also qualify for Title I-A funding. If a nonpublic school student resides in a Title I attendance zone, he or she is considered Title I eligible. A Title I attendance zone is a geographic area in which children who are normally served by a specific school reside; within an attendance zone the share of children from low-income families must be at least as high as the share of low-income families served by the district as a whole. Funding for nonpublic school students is allocated to the New York City Department of Education, which in turn provides Title I services—rather than funds—to nonpublic school students who are eligible.

Although a student may be considered Title I-A eligible, and therefore generate Title 1 funding for his or her state and district, the student will not benefit from that funding unless he or she attends a “Title I-A school.” In general, a school must have a poverty rate equal to at least 35.0 percent in order to receive Title I-A funding. Districts, however, have flexibility in setting this poverty cutoff rate, so long as it is not set below 35.0 percent. Poverty cutoff rates can vary each year.11

At the district level in New York City, poverty cutoff rates are established by county and based on individual students’ eligibility for free lunch. Students are eligible for free lunch if their family income is at or below 130.0 percent of the federal poverty level, as self-reported on lunch eligibility forms. Students are also eligible if their family receives public assistance from a program with income eligibility limits that are lower than those required to receive free lunch, such as TANF or food stamps. The poverty rate is the number of students eligible for free lunch divided by total student enrollment. Because free lunch eligibility uses a higher income threshold than the SAIPE estimate, the number of students eligible for Title I-A in New York City is greater than the number of students who are eligible under federal guidelines; it is the federal eligibility count that determines the overall grant amounts.

Once the poverty cutoff rate is established, Title I-A funds are allocated to schools that have a poverty rate equal to or greater than the poverty rate of the county in which the school is located. Thus, even if a New York City student is eligible for free lunch—and therefore Title I-A—the school may not receive the per capita funding for that student if the school does not meet the county poverty cutoff. There is, however, one exception: students in temporary housing are automatically considered Title I-A eligible, and a school will receive a per capita grant for these students regardless of its designation as a Title I-eligible school. A student is considered living in temporary housing if he or she lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence, including students who share housing with other families because of economic hardship, or are awaiting foster care placement.

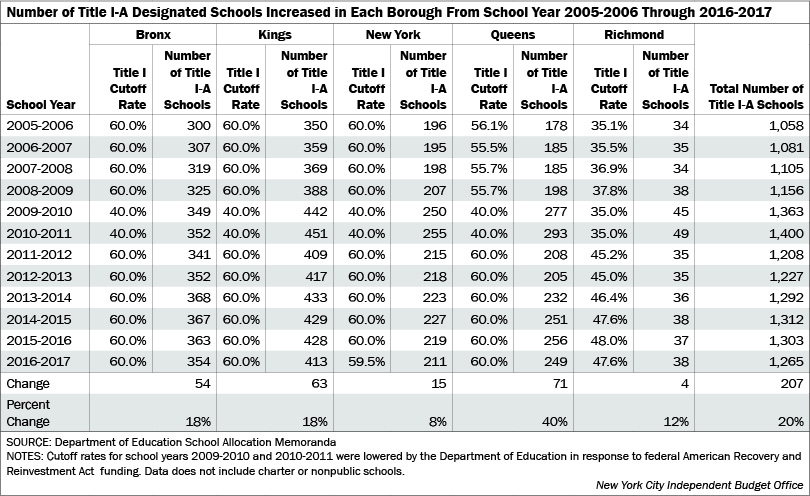

During the 2009-2010 and 2010-2011 school years, additional Title I-A funding was made available to school districts throughout the country under the federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). In order to provide funding for a broader group of schools, the poverty cutoff rate was reduced for each county. In addition, the county poverty cutoff rates for those school years were determined by the number of free and reduced priced lunch eligible pupils divided by total student enrollment. Other than the drops in the poverty cutoff rates in 2009-2010 and 2010-2011 when the temporary changes were in effect, the cutoff rates for Bronx and Kings counties have remained steady at 60.0 percent. New York County’s poverty cutoff rates mirrored those for Bronx and Kings until school year 2016-2017, when it edged down to 59.5 percent. Queens County’s cutoff rate was slightly lower than the rate for Bronx, Kings, and New York counties from school years 2005-2006 through 2010-2011, roughly 56 percent; in 2011-2012, it increased to 60.0 percent and has remained there since. Richmond County’s cutoff rate ranged from 35.0 percent to nearly 38 percent from 2005-2006 through 2010-2011, and then generally increased until 2016-2017, when the cutoff rate was 47.6 percent.

New York City Schools and Title I Eligibility

As noted in the previous section, in New York City a student is Title I-A eligible if he or she qualifies for free lunch, which is a broader classification compared with qualifying as a federally eligible formula child. But a Title I-A eligible student’s school will not receive per capita Title I-A funding if the school he or she attends does not meet or exceed the county poverty cutoff rate, unless that student is living in temporary housing. In New York City, as the number of students eligible for Title I-A increased, each county saw a corresponding increase in the number of traditional public schools being designated as Title I-A from 2005-2006 through 2016-2017. The increases were largest in Queens County, which added 71 schools, an increase of nearly 40 percent. Overall, from 2005-2006 through 2016-2017 the number of Title I-A eligible traditional public schools across the city increased from 1,058 to 1,265, or nearly 20 percent, with 207 additional schools receiving Title I-A funding.

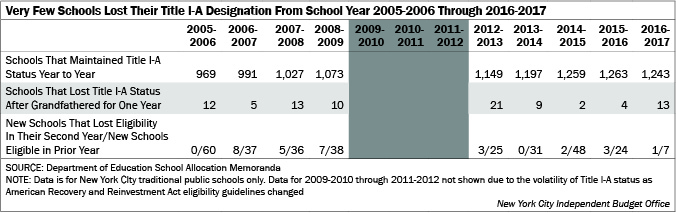

New York City traditional public schools nearly always maintain their Title I-A designation from year to year. ESEA supports this continuity by providing local educational agencies the flexibility to preserve Title I-A funding if an existing Title I-A school does not meet the county poverty cutoff rate in the next school year. The school’s status is grandfathered for one year; if the school fails to meet the county poverty cutoff rate in the following year, it will no longer receive Title I-A funds. However, few schools—less than 2 percent in any school year— lost their Title I-A status after being grandfathered for one year.12

All new schools established in a Title I attendance zone are Title I-A eligible during their first year of operation regardless of their poverty rate. Recall that a Title I attendance zone is a geographical area in which children who are normally served by a specific school reside, and the percentage of children from low-income families in the area is at least as high as the percentage of low-income families served by the school district as a whole. To receive Title I-A funding in subsequent years, however, the school must meet the standard county poverty cutoff rate; new schools are not grandfathered to receive funding if they do not meet the cutoff rate in their second year. In New York City, few new schools lost their Title I-A designation in their second year. For school years 2005-2006 through 2016-2017, only a handful of new schools failed to meet the county cutoff rate after their first year of operation. In the most recent year for which data is available, only one out of seven schools that were new in 2015-2016 lost its Title I-A designation the following year.

With the number of Title I-A eligible school in New York City increasing, one would expect the amount of funding for the city to increase as well. But funding has not always kept pace with need.

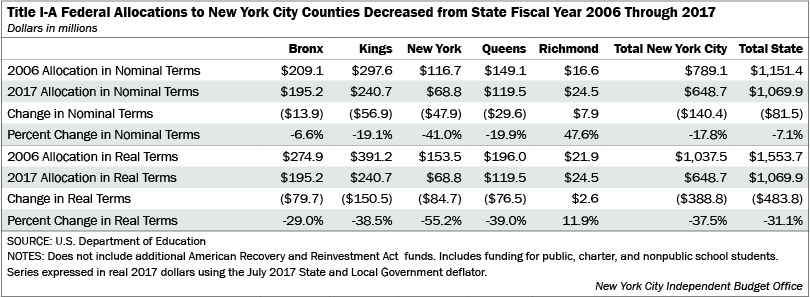

A Decline in Title I-A Funding for New York State and City

Title I-A funding for New York State totaled $1.07 billion in state fiscal year 2017, $81.5 million less than in state fiscal year 2006, a drop of 7.1 percent in nominal terms and 31.1 percent when adjusted for inflation. But not all parts of New York State were affected equally. The city’s share of state Title I-A funding has declined while the share received elsewhere in the state has increased. As a result, the drop in the city’s Title I-A funding has been particularly steep.

While school districts outside of New York City collectively saw their Title I-A funding increase from state fiscal year 2006 through 2017, New York City experienced a sharp decline in funding of $140.4 million, or 17.8 percent (37.5 percent when adjusted for inflation). Within the city, New York County saw the largest relative decline in Title I-A funding over the period, losing $47.9 million, a decrease of 41.0 percent in nominal terms, or 55.2 percent in real terms. In contrast, Richmond County was the only county in which Title I-A funding rose, an increase of $7.9 million (47.6 percent); adjusted for inflation, the increase was 11.9 percent.

Population Shifts in New York and Nationally Drive Funding Changes

Title I-A funding allocations from the U.S. Department of Education are derived from a number of grant formulas, and while each grant formula is different, all of them take into account the number of children ages 5 to 17 who live in poverty, also known as formula, or federally eligible, children. The number of formula children determines the amount each state receives from the federal government, and in turn, the amount each school district receives from the state. As the number of formula children changes within the state and school district, so too will the amount of Title I-A funding. However, because federal appropriations are fixed each year, the funding received by any one school district is also affected by changes in the number of formula children both elsewhere in that state and in other states.

In New York City, the number of formula children—essentially children living in poverty—decreased by 36,087 from school year 2005-2006 through 2016-2017, an 8.9 percent drop. In contrast, the rest of New York State saw a 24.2 percent increase in the number of formula children and the state as a whole experienced a net increase of 3.2 percent, or 20,363 children.

Despite this increase in the number of New York State children living in poverty, the level of Title I-A funding received by New York State has declined. There are two reasons underlying this trend: the population of children eligible for Title I-A nationwide has grown more rapidly than federal funding for the program and New York State’s share of eligible children has declined.

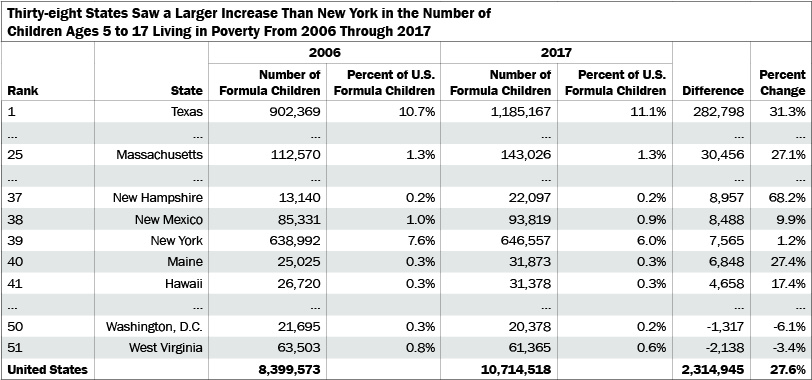

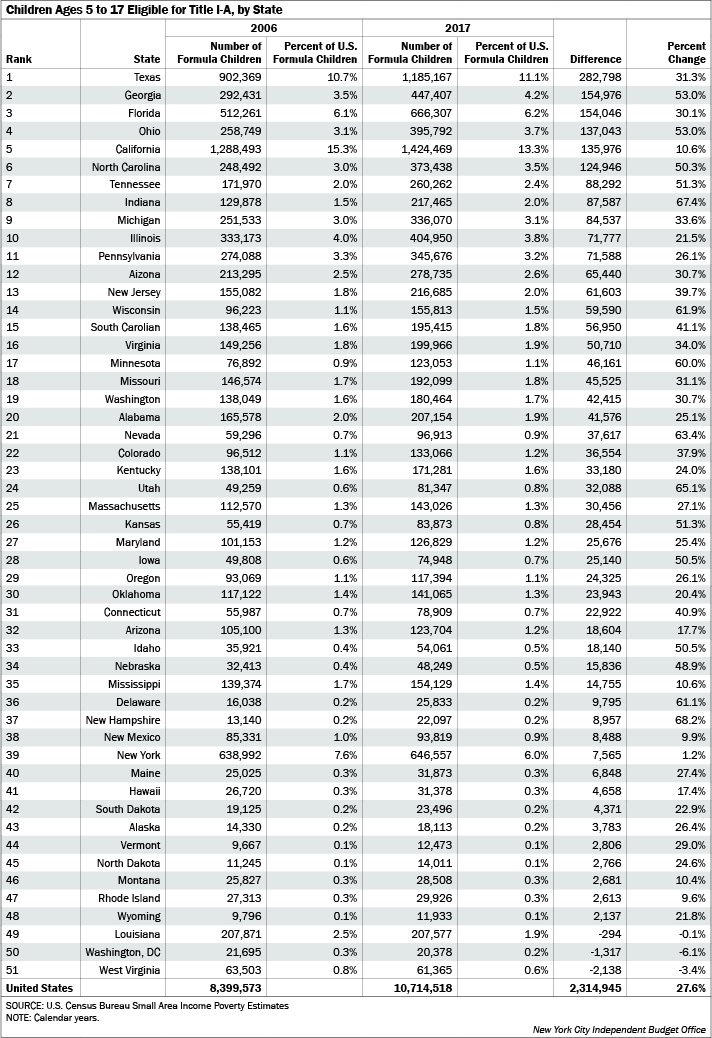

Although the population of eligible children rose 27.6 percent nationwide from calendar year 2006 through 2017, federal spending for Title I-A only grew 17 percent, or $2.2 billion. Putting this in context, New York State alone received over $1 billion each year during this period. Because Title I-A, and ESEA as a whole, is a discretionary program, Congress does not have to fully fund it to its authorized level each year.14 When underfunding occurs, reductions to state allocations are proportional to the state’s share of formula children. With proportional reductions already in place, the additional federal funding did not keep pace with the growing numbers of formula children nationwide and the associated funding needed to serve them. Thirty-eight states saw a larger increase in their number of formula children than New York State. The top six states (Texas, Georgia, Florida, Ohio, California, and North Carolina) saw a combined increase of close to 1 million formula children; only two states—Louisiana and West Virginia—and Washington D.C. experienced a decline.

At the same time that the number of children federally eligible for Title I-A was growing more rapidly nationwide than in New York State, New York City’s share of the state’s child count—formula children—decreased from calendar year 2006 through 2017. In 2006, New York City was home to 406,843 out of 640,079 formula children statewide, 64 percent of the eligible population. By 2017, New York City had just 56 percent of New York State’s formula children—370,756 out of 660,442.

As a result, New York City’s proportional funding allocation decreased by 8 percentage points from state fiscal year 2006 through 2017. In 2006, the city received $789 million out of New York State’s nearly $1.2 billion, amounting to 69 percent of the state’s Title I allocation. In 2017, the city’s share decreased to 61 percent of the state’s total.

With a large number of New York City public schools maintaining or gaining Title I-A status, the decreasing pot of funding must be distributed across an increasing number of eligible schools. Even with federal statutes that are designed to maintain a district’s funding—at least for one year—these statutory protections can only do so much as district needs climb and federal funding for Title I-A remains close to stagnant.

The “New” ESEA: The Every Student Succeeds Act

In December 2015, President Obama reauthorized the Elementary and Secondary Education Act through the Every Student Succeeds Act. While ESSA seeks to return more oversight and discretion to state educational agencies, the funding mechanisms were left unchanged, with each state receiving funds in the same manner that it did under No Child Left Behind. However, ESSA directed the Institute for Education Sciences to evaluate the impact current funding formulas have on school districts. The institute is an independent, nonpartisan office within the U.S. Department of Education, tasked with providing scientific evidence to help shape education policy.

Changes to ESSA policies continue to be made. In March 2017, accountability regulations developed during the last year of the Obama Administration were blocked from taking effect by the Trump Administration. The fate of the accountability regulations was hotly contested. Issued in November 2016, the regulations provided details for how states and school districts were to measure student performance under ESSA and extended the 2015 statute’s deadline for states to implement new accountability systems until the 2018-2019 school year. With the regulations revoked, the U.S. Department of Education was forced to create a new template to provide states with guidance on what was “absolutely necessary” to include in their accountability plans. The accountability implementation deadline, however, remained the same.

Fiscal changes under the Trump Administration have—so far—had little impact on the Title I-A program despite various proposals from the U.S. Department of Education and the White House. The Trump Administration’s 2018 budget proposal maintained flat Title I-A funding compared with 2017 levels, with an additional $1 billion earmarked specifically for expanding school choice. This new grant program encouraged school districts to adopt practices that would allow local, state, and federal dollars to “follow” individual children. Referred to as portability, this would, in effect, remove the requirement of a school to be Title I-A eligible in order to receive aid under the program, thereby allowing every eligible student to “see” their funding. But this program did not make it into the final omnibus budget bill passed by Congress and signed by the President in March 2018. Instead, Title I-A funding was increased by $470 million, a rise of 3 percent, with no changes to the grant formulas.13

Future Funding Constraints?

Title I-A, part of the largest federal program supporting elementary and secondary education, provided more than $648 million to New York City in 2017 with the goal of improving educational opportunities and outcomes for disadvantaged students. But the city’s allocation of Title I-A funds has been declining. Since school year 2005-2006, New York City’s allocation has fallen by $140.4 million, a decline of 17.8 percent (37.5 percent in inflation-adjusted terms).

There are several factors contributing to this. Federal funding for Title I-A has grown by $2.2 billion over calendar years 2006 through 2017, an increase of 17 percent. But this increase has not kept pace with need. Over that same span, the number of eligible children nationwide rose by nearly 28 percent.

While New York State has had an increase in the number of Title I-A eligible children over the 2006-2017 period, the increase in the number of children here has lagged the rise in many other states. Part of the reason is because New York City has seen a decline in the number of eligible children—from 406,843 in 2006 to 370,756 in 2017. Despite the decline in eligible children in the city, the number of city schools eligible for Title I-A funds has been climbing—from 1,058 in 2006 to 1,265 in 2017, an increase of nearly 20 percent.

Together, these fiscal and demographic factors have led to New York State receiving less Title I-A funding from the federal government, and New York City has borne the brunt of the state’s decline. As a result, this smaller pie of New York City Title I-A funding must be allocated among a larger cohort of schools entitled to a slice.

Looking ahead, it is unlikely that under the Trump Administration federal funding for Title I-A will increase enough to offset the eligibility shifts on the local and state levels. If federal funding remains flat, or close to flat, it is also likely that states and school districts will have to either find ways to more efficiently provide services currently funded with Title I, use their own funding to maintain those services, or cut back on services currently offered.

Prepared by Erica Vladimer

PDF version available here.

CORRECTION: This report has been revised to reflect an editing error on the front page reflecting the increase in the number of Title I-A schools.

Appendix

Endnotes

1Selected Statistics From the Public Elementary and Secondary Education Universe: School Year 2014–15, National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2016/2016076.pdf

2http://www.air.org/sites/default/files/downloads/report/Title-I-at-50-rev.pdf

3ESEA of 1965, Public Law 89-10, Section 201

4ESSA of 2015, Public Law 114-95, Section 1001rf

5https://www.census.gov/did/www/saipe/about/index.html

6http://www.air.org/sites/default/files/downloads/report/Title-I-at-50-rev.pdf

7Under No Child Left Behind, states generally reserve up to 1 percent of their allocations for administration and 4 percent for school improvement. Under the Every Students Succeeds Act, states must set aside the greater of either 7 percent of their Title I, Part A funding under ESSA, or the sum of their set aside under No Child Left Behind plus the amount a state received under Section 1003(g) under No Child Left Behind. States are required to use set aside funding for administrative services and to provide districts with technical assistance and support, as well as school improvement services.

8What Title I Portability Would Mean for the Distribution of Federal Education Aid, Nora Gordon.

9Elementary and Secondary Education Act, as amended by the Every Student Succeeds Act, Section 1124(c)(2)

10Elementary and Secondary Education Act, as amended by the Every Student Succeeds Act, Section 1124(c)(2)

11ESEA Section 1113(a)(5) allows a district to measure poverty cutoff rates by using either one or a composite of the following indicators: number of children ages 5 through 17 counted in the most recent Small Area Income Poverty Estimates; number of children eligible for free and reduced price lunches; number of children in families receiving government assistance such as TANF; and the number of children eligible to receive medical assistance under the Medicaid program.

12Data for school year 2009-2010 through 2011-2012 are not shown due to the volatility of Title I-A status as ARRA eligibility guidelines changed.

13Although the White House also proposed to eliminate Title II-A funding, which supports professional development programs for both teachers and principals, funding remained flat at $2.1 billion. In state fiscal year 2017, New York City received $108 million in Title II-A funding.

Receive notification of free reports by e-mail