Albany Shifts the Burden: As the Cost for Sheltering the Homeless Rises,

Federal & State Funds are Increasingly Tapped

October 2015

Albany Shifts the Burden:

As the Cost for Sheltering the Homeless

Rises, Federal & City Funds Are Increasingly Tapped

PDF version available

here.

Summary

As the number

of families and single adults in the city’s homeless shelters

has grown dramatically in recent years, the cost of sheltering

them also has increased markedly. Spending on the city’s shelter

system—including city, state, and federal funds—has risen from

$604 million in fiscal year 2007 to an estimated $976 million in

2015, an increase of 62 percent.

Legislators, advocates, and other New

Yorkers have expressed concern that the city spends this much on

temporary responses to homelessness rather than longer-term

solutions or to meet other city needs. But a substantial share

of the funding comes from Washington and Albany and cannot

simply be redirected. This

makes understanding the distribution of costs among the three

levels of government for the two different homeless

populations–families and single adults–essential. As the de

Blasio Administration seeks to reduce the shelter population,

IBO has examined recent shifts in how shelter costs are funded

and what these shifts imply for the use of potential savings if

the shelter population were to decrease. Among our findings:

-

For many homeless families, federal public assistance programs

fund a large part of the cost of shelter. The state determines

the cost-sharing for these programs and in 2012 Albany shifted a

larger share of the costs for family shelter onto federal

funding streams.

-

As a result, federal dollars have covered an increasing share of

family shelter expenses, growing from 32 percent ($120 million)

in 2007 to 58 percent ($310 million) in 2014.

-

Other changes implemented in Albany have reduced the state’s

contribution to fund shelters for single adults, leaving the city

to fund the increased costs associated with the rising adult

shelter population.

-

In 2007, the city paid $104 million, or 53 percent, of the total

$196 million cost for sheltering homeless single adults, not

including intracity funds. In

2014, when the total cost for sheltering homeless single adults

grew to $343 million, the city’s share was $252 million, or 73

percent of the total.

The alternative uses for any potential shelter savings derived

from a reduction in the city’s shelter population depends on the

source of the funding. A reduction in the number of homeless

families would have less of an effect on city costs—and

potential savings—than a commensurate reduction in the number of

homeless single adults. Still, efforts to reduce the homeless

population should be viewed through a broader lens than what

generates the most city savings on shelter costs.

Introduction

In recent years, as the number of homeless households in New York City

has swelled, so too has the cost of providing shelter. The de Blasio

Administration has made reducing the shelter census a priority,

introducing a host of new rental assistance programs aimed at moving

households from shelter into permanent housing. The funding sources New

York City uses to pay for homeless shelters vary by household type and

public assistance eligibility, so that the share of the costs borne by

the city, state, and federal governments differ for the various

populations. Thus the extent of any savings for the city stemming from a

reduction in the shelter census depends on the particular segment of the

shelter population that is declining.

In this brief, the Independent Budget Office uses data from 2007 through

2014 to explain how city shelters are funded and the way in which this

funding differs between shelters for families versus those for single

adults. (Years refer to city fiscal years unless otherwise specified.)

We examine the impact of state-level changes made during the study

period on how shelter costs are shared among city, state, and federal

resources. Finally, we use this information to explore how the rules

associated with the different funding sources determine the extent to

which savings resulting from a smaller shelter population could be

redirected to other city priorities.

Background

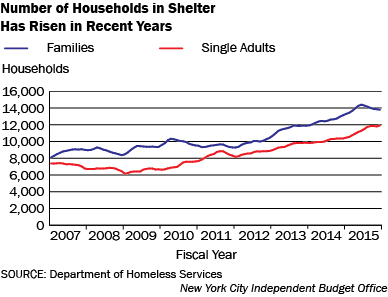

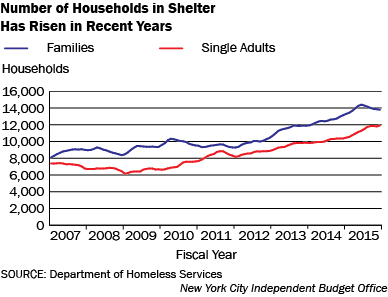

The number of households in shelter has risen dramatically in recent

years. The increase can be seen in both of the two distinct groups that

the Department of Homeless Services (DHS) serves within its shelter

system: families and single adults. (Families include both households

with minor children and households consisting only of related adults.)

In June 2015, an average of 13,795 family households and 11,927 single

adult households stayed in the city’s shelter system each night, for a

total of approximately 56,000 individuals. The average number of family

households in shelter has grown by 71 percent since 2007, the first year

of our study period, while the number of single adult households grew by

61 percent.

This population growth reflects both an increase in households entering

the shelter system and longer lengths of stay once in shelter. To

accommodate all of these households, DHS currently funds 271 shelter

facilities, a mix of shelters operated directly by the city and through

contracts with not-for-profit organizations and private landlords. The

analysis in this report looks at the homeless shelter population

associated with DHS and does not include additional homeless

populations, such as victims of domestic violence, persons living with

HIV/AIDS, and runaway youth, served through the Human Resources

Administration and the Department of Youth and Community Development.

Rising Number of Homeless, Rising Shelter Costs.

The increase in the shelter population has led to an increase in shelter

costs. DHS spent $377 million on family shelters and $227 million on

single adult shelters in 2007. Since then, spending on family shelter

grew 59 percent and is projected to total $598 million in 2015 (final

figures will be available with the release of the Comptroller’s

Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for 2015), while spending on

single adult shelter grew by 66 percent to a budgeted total of $378

million. Spending totals include shelter operations, shelter intake and

placement, and shelter administration and support. These cost increases

reflect per capita costs associated with a growing shelter population as

well as rising fixed costs such as rents for leased shelter space and

wages of shelter staff. In 2015, family and single adult shelter costs

combined are projected to account for 83 percent of DHS’s $1.2 billion

budget, with the remainder of department spending going towards programs

such as homelessness prevention and outreach, aftercare services for

households that have exited shelter, and general agency administration.

NOTE:

Shelter costs are funded by the city, state, and federal governments.

All years reflect actual costs except for 2015, which is the final

budgeted amount.

Mayoral Priority to Reduce Shelter Census. The

elimination of the rental assistance program for homeless families known

as Advantage over three years ago is widely viewed as contributing to

the present spike in the homeless shelter population. Since taking

office in January 2014, the de Blasio Administration has created a

number of programs to move households out of shelters and into permanent

housing. Most notably, the Mayor has created Living in Communities

(LINC), a series of programs, each of which targets a particular subset

of the shelter population.

The first LINC programs, rolled out in the fall of 2014, were designed

specifically for families with minor children living in shelter. These

rental assistance programs appeared to have some initial effect in

reducing the family shelter census; as of June 2015, the number of

households in the family shelter system had decreased by 4 percent from

its peak in December 2014. DHS subsequently launched additional LINC

programs to serve single adults in December 2014. Despite the new

programs, however, the single adult population rose 6 percent from

December 2014 through June 2015. It may be well into 2016 before it is

clear what effect, if any, the LINC programs have on the adult shelter

population. (See IBO’s reports on

LINC and

other homeless rental

assistance programs for more details.)

Family Shelters

Funded Primarily Through Federal Public Assistance Funds

Public assistance plays a major role in paying for homeless shelters in

New York City, particularly for families. All families and single adults

entering one of the city’s homeless shelters are required to apply for

public assistance if they are not already enrolled. Under state rules,

the city may use the housing allowance awarded as part of any eligible

family’s public assistance grant to cover the cost of their homeless

shelter stay. For single adults, however, the state only permits public

assistance funds to be used for a relatively small, set number of

households in shelter each year. Because public assistance costs are

shared to varying degrees by the federal, state, and city governments,

maximizing the number of homeless households on public

assistance—particularly for families—reduces the city’s share of total

shelter costs. In recent years, state-level changes to the public

assistance cost-sharing formulas have resulted in the majority of

funding for family shelters coming from federal sources.

Types of Public Assistance. Households in New

York City can qualify for one of several public assistance programs,

each of which has distinct cost-sharing rules. Eligibility for public

assistance depends on a household’s composition and compliance with

program requirements. The main public assistance programs New York City

uses to fund shelter stays are Family Assistance, Emergency Assistance

for Families (EAF), and Safety Net Assistance.

-

Family Assistance

is a cash assistance program created through the federal Temporary

Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) block grant program to serve

families with minor children.1 In order to be eligible

for Family Assistance, a household must be able to demonstrate that

they are U.S. citizens, or that they have been legal residents for

at least five years, and able adults must comply with federally

established work requirements. Benefits are time-limited to 5 years

(or a total of 60 months), and any TANF-based benefits received in

another state are counted towards this time limit.

-

Emergency Assistance

for Families is also a TANF program for families with minor

children, intended to address short-term sudden and unforeseen

crises. EAF is limited to a maximum of four months, time which does

not count against the Family Assistance five-year limit.

-

Safety Net Assistance

is a state-created program to aid families ineligible for or who

have timed out of Family Assistance, as well as single adults. To

qualify for Safety Net, a household must prove that they are U.S.

citizens or legal residents, and meet work requirements similar to

those for Family Assistance. Safety Net has no time limit, but up to

two years counts against the TANF five-year time limit if at a later

point a household receiving Safety Net becomes eligible for Family

Assistance (for example, if an adult couple has a baby).

Two additional public assistance programs contribute a very small amount

of funding for homeless shelter stays. Safety Net-Federally

Participating is a TANF-funded subset of Safety Net for households that

qualify for Family Assistance but are unable to receive cash-based

assistance due to drug or alcohol abuse. Emergency Assistance for Adults

is for adult households that are facing unforeseeable, short-term

crises, with costs evenly split between the city and state. In order to

qualify for the assistance, at least one member of the household must

qualify for Supplemental Security Income.

Public Assistance Cost Sharing. Public

assistance costs are shared by the city, state, and federal governments

with the funding shares varying for each program. New York State

controls how the costs are split; this includes controlling the use of

federal TANF funds, which come to the state as a block grant, allowing

the state wide discretion in deciding how to allocate the funds.

State decisions have changed how public assistance programs are funded

over time. Through state fiscal year 2010-2011, the TANF-based Family

Assistance and EAF programs were 50 percent federally funded, with the

remaining costs evenly shared between the state and city. The Safety Net

program was funded with 50 percent state funds and 50 percent city

funds. Faced with the need to close a $10 billion budget gap for state

fiscal year 2011-2012, New York State sought to minimize the use of

state funds to cover public assistance costs. It changed the

cost-sharing rules so that the Family Assistance and EAF programs were

fully funded through the federal TANF block grant. At the same time, the

state reduced the share of Safety Net costs it covered to 29 percent,

leaving the city to pay the remaining 71 percent.2 The result

of these changes for the city was twofold—the city no longer had a

cost-sharing obligation for Family Assistance costs, but now was

responsible for a larger share of Safety Net costs. Although the state’s

fiscal condition is now much stronger, in the state fiscal year

2015-2016 budget, New York State further revised the cost sharing rules

by reducing the share of the EAF program funded by the federal

government from 100 percent to 90 percent, with the city picking up the

remaining 10 percent of costs. The state reported that the

reintroduction of a city cost share was to “encourage fiscal

discipline” in New York City after EAF spending markedly rose with the

switch to the program being 100 percent federally funded.3

|

Main Public Assistance Programs Used to Fund Homeless Shelters

|

|

Program Name

|

Eligible Households

|

Cost Sharing

|

|

State Fiscal Year

2010-2011 & Earlier

|

State Fiscal Years

2011-2012 Through 2014-2015

|

State Fiscal

Year 2015-2016

|

|

Family Assistance

|

Families with minor

children; time limited to five years

|

50% Federal

25% State

25% City

|

100% Federal

|

No change

|

|

Emergency Assistance

For Families

|

Families with minor

children;

time limited to four months

|

50% Federal

25% State

25% City

|

100% Federal

|

90% Federal

10% City

|

|

Safety Net Assistance

|

Families ineligible

for or timed out of Family Assistance, single adults; no time

limit

|

50% State

50% City

|

29% State

71% City

|

No change

|

|

New York City Independent Budget Office

|

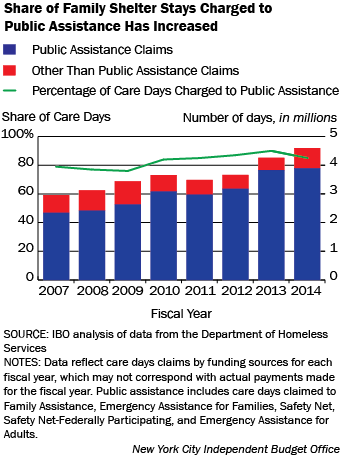

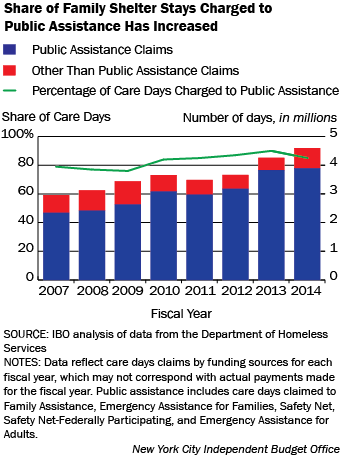

Share of Family Stays Charged to Public

Assistance Grew. The share of shelter stays charged to public

assistance increased as the number of families in shelter grew. In 2007,

79 percent of family shelter stays were charged to a public assistance

program. This share then peaked at 90 percent in 2013 before falling to

85 percent in 2014. (Over the same period, the city’s total public

assistance caseload declined by 9 percent.) On average, 83 percent of

family shelter stays were charged to public assistance each year over

the study period.

Family shelter stays are tracked and funded on the basis of “care days,”

or the number of days a family has resided in the shelter system. This

allows DHS to identify the number of shelter days provided to families,

even as families move between various shelter facilities or change

public assistance status. Family shelter costs are calculated through a

per diem rate established for each shelter facility multiplied by the

number of care days provided at that facility. Costs are then assigned

to the appropriate public assistance program if the household is

eligible and claims for reimbursement through the public assistance

program are submitted to the state. If the household is ineligible for

public assistance, costs are charged solely to city funds. For this

study IBO was able to obtain data from DHS on care days and funding

claims through 2014.

Family Assistance Remains Largest Share of Family Shelter

Public Assistance Claims. As the number of shelter stays

rose from 2007 through 2014, the number of care days claimed to Family

Assistance increased by 47 percent. Despite the growth in the overall

number of claims, the share of public assistance claims charged to

Family Assistance actually fell about 7 percentage points over the study

period, from 64 percent in 2007 to 57 percent in 2014. This decrease in

the share of care days charged to Family Assistance likely reflected

families reaching the time limit for this benefit, as shelter stays, on

average, became longer. (The average length of stay for a family with

minor children rose from 292 days in 2007 to 427 days in 2014.)

Safety Net Assistance was the second largest public assistance program

funding family shelter stays from 2007 through 2014. As was the case for

Family Assistance, as the overall number of shelter care days increased

over the study period, so did the number charged to Safety Net, which

nearly doubled from 2007 through 2014. Looking at public assistance care

day claims in terms of shares, the fall in the share of Family

Assistance corresponds with the rise in the share of claims made to

Safety Net Assistance and Emergency Assistance for Families. The use of

Safety Net funds remained relatively stable from 2007 through 2011,

averaging 33 percent. During this time, on average, only 1 percent of

public assistance care days claimed were billed to EAF, which has a four

month time limit and is intended to address short-term crises. A shift

in these trends occurred in 2012—the year that the cost-sharing changes

were made—when Safety Net dropped down to 28 percent as EAF rose

to 10 percent. EAF does not count toward a family’s five-year TANF time

limit. At the end of the four-month period, the household could then be

switched to Family Assistance or Safety Net if they were eligible, or if

ineligible, the shelter stay began to be paid for exclusively out of

city funds. EAF use peaked at 13 percent of all care days claimed to

public assistance in 2013.

In February 2014, in response to the ballooning number of claims being

made to EAF, the state issued a directive clarifying that the only

families eligible for EAF were those experiencing a short-term crisis

that could reasonably be expected to resolve within the four-month

window. Families likely to require public assistance beyond four months

were to be assigned directly to either Family Assistance or Safety Net,

depending on eligibility. After the new directive was issued, the use of

EAF in 2014 dropped back closer to its 2011 level, accounting for only 2

percent of care day claims. As the number of care days charged to EAF

dropped in 2014, there was a corresponding rise in the number of care

days charged to Safety Net. Between 2013 and 2014, Safety Net care days

rose 12 percentage points from 29 percent up to 41 percent. This growth

in Safety Net at the end of the study period is closely related to the

changes the state made on the use of Emergency Assistance to Families

and a decline in shelter care days eligible to be charged to Family

Assistance.

NOTE:

Data reflects care day claims by funding sources for each fiscal year,

which may not correspond with actual payments made during the fiscal

year. Safety Net-Federally Participating is reflected in the Family

Assistance totals. Emergency Assistance to Adults is not included in the

calculation; over the study period, Emergency Assistance to Adults

averaged 0.03 percent of care day claims.

Federal Funds Cover

Larger Share of Family Shelter Costs.

Given the mix of public assistance claims and the 2012 state-led changes

to the cost sharing—which shifted more public assistance costs onto

federal funding sources—the share of family shelter costs paid by the

federal government rose during the study period. In 2011, federal

funding became the majority source of family shelter funding.4

The share of shelter costs paid through city and state funds fell during

the study period, with state funding showing the greatest reduction.

Federal sources paid for 32 percent of family shelter costs in 2007, a

share that held relatively constant through 2010. In 2011, the city

received a one-time $21 million grant in additional TANF funds through

the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, which helped to raise the

federal share to 51 percent. With the state’s public assistance cost-sharing changes fully in place in 2012, the federal share rose to 60

percent and then peaked at 61 percent in 2013. Federal funds increased

even as the share of Family Assistance claims fell somewhat. This is

because the increase in EAF claims, which were also fully federally

funded, offset the loss in Family Assistance claims. As the number of

EAF claims then fell in 2014, the share of family shelter costs covered

by the federal government decreased slightly in 2014, falling to 58

percent. The amount of federal funding, however, has gone up every year

as the family shelter population has trended upward—rising from $120

million in 2007 to $310 million in 2014.

As the federal share of family shelter costs increased, the state and

city shares have decreased. In 2007, state sources covered 26 percent of

costs, a share that remained relatively constant through 2010. In 2011,

with the increase in federal recovery act funds, the state share fell to

12 percent, 13 percentage points lower than the 25 percent share seen

the year before. During this same time period, the city’s share of

funding declined more gradually, falling 5 percentage points, from 42

percent in 2007 to 37 percent in 2011. After the state implemented its

cost-sharing changes in 2012, eliminating state support for Family

Assistance and EAF claims and reducing its reimbursement for Safety Net

claims, the state’s share of overall shelter costs fell an additional 6

percentage points. These same changes had mixed implications for the

city’s share of costs. With Family Assistance and EAF now 100 percent

federally funded, the city no longer had to contribute to those costs,

but the city did have to pick up a larger portion of Safety Net costs

from the state. The net effect of these changes resulted in a modest

decrease in the city’s share of family shelter funding, from 37 percent

in 2011 to 34 percent in 2012.

Since then, as more of the caseload shifted from Family Assistance to

Safety Net, the state’s share of family shelter costs has increased from

6 percent in 2012 to 10 percent in 2014, while the city’s share remained

relatively stable, averaging 32 percent. In dollar terms, total state

funding for family shelters fell from $97 million in 2007 to $51

million in 2014—a 44 percent decline—despite the overall increase in

family shelter stays. Meanwhile city funding has increased by 8 percent,

from $160 million in 2007 to $173 million in 2014.

Single Adult Shelter

Costs Paid Primarily With City Funds

Unlike funding for family shelters, public assistance plays a minimal

role in funding shelters for single adults. Instead, single adult

shelter costs are primarily paid through city funds with some additional

funding through a state grant, and a small amount paid through federal

funds. State changes in funding rules during the study period shifted

adult shelter costs away from the state and more towards the city.

Single adult shelter funding is not derived from care days and per diem

rates, the model used for family shelters. Shelter funding for single

adults is instead based upon each provider’s actual expenses of

operating a shelter at a given bed capacity.5

In another difference from how family shelters are funded, public

assistance plays only a small role in covering adult shelter costs.

Single adults do not qualify for Family Assistance or EAF, as these

programs require a minor child as part of the household composition.

While single adults may qualify for Safety Net, the state limits the

city’s use of Safety Net to pay for homeless shelter stays at a fixed

amount of funding each year. Safety Net funded an average of $11

million, or about 4 percent of the overall adult shelter costs during

the study period. In place of using public assistance as the primary

funding model to pay for shelters like that for families, the state

provides an annual grant specifically designated to pay for single adult

shelters in New York City, known as the “adult shelter cap.” Under this

grant, the state will reimburse the city for 50 percent of single adult

shelter costs until the cap amount—which has been reduced over the study

period—is reached.

State Increases City Share of Adult Shelter

Costs. In state fiscal years 2010-2011 and 2011-2012, the

state reduced its contribution towards the cost of adult shelters,

leaving the city to bear a larger share of costs even as the adult

shelter population continued to increase.6 Prior to state

fiscal year 2010-2011, New York State payments for single adult shelters

were based on previous years’ expenses, up to the cap. The adult shelter

cap averaged $82 million from 2007 through 2011. The city could also

request up to $10 million annually in additional funding above the cap

to improve shelter conditions for medically frail adults. Beginning in

2011, the additional costs of sheltering the medically frail were to be

included in the shelter cap amount. Then in 2012, the state removed

language that tied funding to prior shelter costs and lowered the

shelter cap to $69 million, where it has remained.

The reduction in the state shelter cap coupled with the growth in the

adult shelter census caused city spending for adult shelter to rise

dramatically over the study period. The cost of single adult shelter was

$196 million in 2007 with the city paying for 53 percent, or $104 million,

of the total and the state picking up 47 percent, or $86 million, of the

costs. (A small amount of adult shelter funding, averaging about 4

percent a year, comes from the federal government through two block

grants, the Emergency Solutions Grant and the Community Development

Block Grant.) As the shelter cap was reduced, the additional cost

associated with the increase in the shelter population was fully borne

by the city. Total adult shelter costs rose to $343 million in 2014,

with the city’s share increasing to $252 million, or 73 percent, of the

total and the state funds dropping to $73 million, or 21 percent, of the

total. (The $73 million contributed by the state in 2014 includes the

$69 million shelter cap as well as the state’s share of funding for the

small number of Safety Net cases).

NOTES:

Through 2011, a portion of the state shelter cap funding went towards

the Departmnet of Homeless Services general operations and outreach programs. Starting in 2012, the

full amount of the shelter cap was applied to the cost of single adult

shelters. Totals do not include intracity funds.

Alternative Uses for

Shelter Savings

The alternative uses for any potential shelter savings derived from a

reduction in the city’s shelter population depends on the underlying

funding source used to pay for that shelter population. Because family

shelters and single adult shelters are funded differently, a reduction

in the number of homeless families would have a very different impact on

city costs—and thus potential savings—than a commensurate reduction in

the number of homeless single adults. Presently, much of the focus of

the de Blasio Administration’s policies has been on the increase in

children and families in the shelter system. The city has designed most

of the new homeless rental assistance and eviction prevention programs

for homeless families with minor children. If these programs are

successful in achieving a significant reduction in the number of family

shelter care days, then any resulting shelter cost savings would largely

free up federal TANF public assistance funds, with smaller savings for

the city and state.

Use of Family Shelter Savings Limited by TANF Rules.

These TANF funds are restricted to welfare-based programs and

initiatives that specifically serve families with minor children and it

would be up to the state, which controls the grant, to determine how any

savings could be used. If the city is able to realize family shelter

savings, New York State has already granted the city permission to

redirect the savings, including federal TANF funds and state Safety Net

funds, towards a rental assistance program that serves repeat and

long-term shelter users (LINC II). The state has also allowed the city

to use federal TANF funds to help pay for a rental assistance program

targeting homeless domestic violence survivors (LINC III). Although

there are federal restrictions on the use of TANF funds, it is possible

that the state could permit the city to expand its use of these funds to

pay for other programs targeting welfare-eligible families with minor

children. Alternatively, the state could choose to use TANF savings to

raise the overall cash assistance grant, which would benefit low-income

households more generally.

Fewer Restrictions on Use of Adult Shelter Savings.

In contrast to family shelter, the additional shelter costs associated

with the rise in the number of homeless single adults has been paid for

almost completely out of city funds. Thus a reduction in the single

adult shelter population would largely free up city funds, an

unrestricted funding source available to the de Blasio Administration.

One option for these savings would be for the city to apply the funds on

a pay-as-you-go basis to fund capital projects, including the

development of affordable and supportive housing.

Although the city has greater flexibility in using savings from single

adult shelters—which are mainly city funds— than savings from family

shelters, the de Blasio Administration has only recently started

directing resources towards reducing the population of single adults in

shelters. Two rental assistance programs, LINC IV and LINC V, were

created for single adults age 60 and older and working adults,

respectively. In addition, the city is currently expanding rental

assistance programs such as LINC VI, previously open only to families

with minor children, to also serve single adults.

Conclusion

Family shelters are funded primarily through public assistance programs,

with the specific program determined by the homeless household’s

composition and eligibility. Public assistance programs are paid out of

a mix of federal, state, and city funds, with the cost-sharing splits

varying by program. State-level changes that took place in 2012 have

since shifted more of the family shelter costs to federal TANF sources

and reduced the city and state shares of shelter costs. Although single

adult shelter costs are funded primarily through city funds, a state

grant that had been an additional source of funding has been reduced in

recent years.

If the city’s goal were simply to reduce its spending on shelter, then

given the underlying funding differences a reduction in the single adult

shelter population would save more in city funds than a reduction in the

family shelter population. As the Mayor looks to decrease the homeless

shelter rolls in the city, it is necessary to understand how homeless

shelters are being funded, and how the underlying funding sources then

inform alternative uses for any potential shelter cost savings.

Report prepared by Sarah Stefanski

Appendix

|

Number of Care

Days Claimed to Public Assistance Programs

|

|

|

Fiscal Year

|

|

2007

|

2008

|

2009

|

2010

|

2011

|

2012

|

2013

|

2014

|

|

Family Assistance

|

1,502,695

|

1,531,832

|

1,740,501

|

2,066,270

|

1,952,557

|

1,939,430

|

2,202,945

|

2,213,254

|

|

Safety Net Assistance

|

822,171

|

870,931

|

876,584

|

908,346

|

948,910

|

897,733

|

1,112,343

|

1,594,841

|

|

Emergency Assistance

For Families

|

7,239

|

3,929

|

5,927

|

101,240

|

64,136

|

332,253

|

509,307

|

83,516

|

|

SOURCE: IBO analysis of data from the Department of Homeless

Services

NOTE: Safety Net-Federally Participating is included in the

totals for Family Assistance.

New York City

Independent Budget Office

|

|

Family Shelter Funding by Revenue Source

Dollars in thousands

|

|

|

Fiscal Year

|

|

2007

|

2008

|

2009

|

2010

|

2011

|

2012

|

2013

|

2014

|

|

Federal

|

$119,730

|

$130,493

|

132,688

|

$154,824

|

$211,033

|

$254,670

|

$297,497

|

$309,848

|

|

State

|

96,827

|

104,462

|

109,637

|

105,895

|

49,848

|

25,963

|

42,083

|

50,788

|

|

City

|

160,005

|

173,863

|

157,414

|

161,101

|

154,631

|

146,320

|

150,978

|

172,840

|

|

TOTAL

|

$376,562

|

$408,818

|

$399,739

|

$421,820

|

$415,512

|

$426,953

|

$490,559

|

533,476

|

|

SOURCES: IBO analysis of data from the Mayor’s Office of

Management and Budget and Office of the New York City

Comptroller

New York City Independent

Budget Office

|

Endnotes

1Under New York State’s TANF rules, a

minor child is defined as under age 18, or under age 19 if enrolled

regularly in secondary education or vocational training. Households with

a pregnant woman may also be considered households with a minor child

for the purposes of Family Assistance eligibility.

2The reduction in state contribution

to Family Assistance and Safety Net was in conjunction with the state

switching the Earned Income Tax Credit benefit from being federally

TANF-funded to being funded at the state level. This freed up TANF funds

for other purposes, including Family Assistance and EAF.

3“2015 Opportunity Agenda—2015-16

Executive Budget,” New York State Department of Budget, pp. 137-138.

4Most of this federal funding, 97 percent, on

average, came through the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families block

grant during the study period. The remaining 3 percent of federal

funding came through the Emergency Solutions Grant, the Community

Development Block Grant, and the Homelessness Prevention and Rapid

Re-Housing program, which was funded through the American Recovery and

Reinvestment Act.

5Neither the family shelter per diem

payment model nor the single adult bed capacity model, however, takes

into account whether a provider serves more clients over shorter shelter

stays or fewer clients over longer stays. With intake and exit

preparation being the most service-intensive parts of a shelter stay,

current reimbursement models provide no incentives for shelter operators

to move clients out of shelter more quickly.

6Changes in the adult shelter cap

funding and rules were effective for the calendar year but reimbursed

based on the state fiscal year.

PDF version available

here.

Receive

notification of free reports by e-mail

Facebook

Twitter

RSS