June 2017

A System in Flux:

New Programs, Administrative Changes Create Challenges for New York City’s Traditional Subsidized Child Care Programs

PDF version available here.

Summary

Mayor de Blasio’s recently announced 3-K for All initiative is the latest in a series of programmatic and administrative changes that have swept across the city’s subsidized child care system. While this system still serves nearly 100,000 children, it has been shrinking in recent years with the implementation of the EarlyLearn program and the increased availability of options such as universal pre-k for 4-year-olds and after-school programs for school-age children that serve as an alternative to traditional child care.

This report looks at how the child care system has evolved over the five years from 2012 through 2016, examining changes in capacity, enrollment, and funding while eyeing what challenges lie ahead. Among our findings:

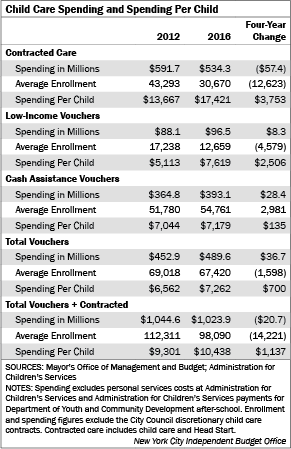

- Total average enrollment in subsidized child care declined by more than 13,600 from 112,311 children in 2012 to 98,677 in 2016.

- As total average enrollment fell over the five-year period, spending declined slightly from $1.04 billion to $1.02 billion. But at the same time, spending per child increased by over $1,100 to reach $10,438 in 2016.

- Most of the enrollment decline occurred in child care contracted by the Administration for Children’s Services with center- based and home-based providers. Over the five years, enrollment with these contracted providers fell to 30,670 in 2016, a decline of over 29 percent.

- So far, the expansion of full-day prekindergarten for 4-year-olds has resulted in only a modest decrease in the use of child care vouchers—which can be used to pay for informal care by neighbors or family as well as for licensed care—by eligible low-income families along with those receiving cash assistance. From 2012 through 2016, average enrollment with vouchers fell by 1,598 to reach 67,420.

Looking ahead, the plan to shift the EarlyLearn program from the Administration for Children’s Services to the Department of Education may bring into sharper focus the disparity in pay and work hours between programs provided in the public schools and those at community-based centers, where recruiting and retaining staff has become an increasing challenge. The implementation of 3-K for All could also present challenges to traditional child care programs as the two compete for similar pools of public funding.

Overlapping Programs

On April 24, 2017 Mayor de Blasio announced the 3-K for All initiative. Building on the successful expansion of universal prekindergarten for 4-year-olds, the new initiative aims to provide free, full-day early childhood education to the city’s 3-year-olds. According to the de Blasio Administration, when fully implemented, 3-K for All will be a key link in a chain of early care and education programs for the city’s children that begins at birth. Given the overlap of the early care and education programs at the Department of Education (DOE) and the EarlyLearn NYC contracted child care program at the Administration for Children’s Services (ACS), the Mayor proposes to merge EarlyLearn into DOE. The integration process would be completed by July 2018.

With these future changes in mind, this report looks at the impact on the city’s subsidized child care system of major policy initiatives that have already taken place such as the implementation of the EarlyLearn contracting system, and the increased availability of programs that can serve as alternatives to traditional child care, including after-school programs for school-age children and pre-kindergarten programs for 4-year-olds. Along the way we will identify important challenges still facing the child care system including funding, enrollment, staff recruitment, and the particular difficulties in serving cash assistance families.

Background. Over the last decade New York City’s subsidized child care system has undergone extensive changes that have reduced its size, even as the city has expanded alternative educational programs for children such as universal prekindergarten and after-school services. Nevertheless, publicly funded child care remains a vital social service for many families: in 2016 an average of 99,000 children were enrolled in subsidized child care, at a total cost of about $1.1 billion. (All years refer to city fiscal years unless otherwise noted.)

Despite recent reductions in the size of the program, the Administration for Children’s Services still administers the largest municipal child care system in the country. Subsidies are offered for three types of child care: informal care provided in the home of an unlicensed provider; family (3 to 8 children) or group family day care (7 to 16 children) provided in the home of a licensed caregiver; and center-based day care in a licensed facility. The latter also includes those Head Start centers throughout the city that ACS administers as the recipient of a federal Head Start grant (other Head Start centers in the city are operated by providers contracting directly with the federal government). ACS Head Start centers offer early childhood care and education programs to eligible children ages 3 and 4 from low-income families. For many years the city-affiliated Head Start centers were administered separately from the child care program, but in the fall of 2012 ACS blended them into one unified system.

Subsidy payments are made either directly to providers under contract with ACS or through vouchers. Informal care is provided solely through vouchers, while family and center-based care are paid by a mix of contracts and vouchers. Rates vary by type of child care, with center-based being the most expensive and informal care the least expensive. Rates also vary by the age of the child, with infants and toddlers the most expensive, preschool children (generally 3- and 4-year-olds) less expensive, and school-age children (generally 5- to 12-year-olds) the least expensive.

Services are provided to two groups: cash assistance families with parents in work or training programs and low-income working families.1Cash assistance families are guaranteed vouchers to pay for care in their choice of center-based child care, family child care, or informal care wherever these services are available. Eligible low-income working families receive vouchers or slots in ACS contracted child care facilities as space permits; they are not guaranteed a subsidy.

The Transition to EarlyLearn

In April 2010, ACS began to lay the groundwork for a new initiative called EarlyLearn NYC, which encompasses all contracted center-based and family child care, as well as the city-affiliated Head Start programs. The primary goal was to improve and standardize quality of care while expanding services to communities with the greatest need. The new EarlyLearn contracts began in October 2012 with many providers new to ACS.

The implementation of EarlyLearn blended two early childhood programs: contracted child care and Head Start. By design, it has had no impact on the number of child care vouchers offered by ACS. In 2012, the last fiscal year prior to EarlyLearn, vouchers were used by about 60 percent of the children enrolled in ACS child care or Head Start.

The new EarlyLearn model also included notable changes in the way that contractors were funded. Whereas prior contracts compensated providers based on budgets associated with a specified child care capacity, EarlyLearn providers were paid a daily rate based on the number of children actually enrolled. In addition, the new contracts required the providers themselves to contribute at least 6.7 percent of total annual operating costs. Finally, under the new system, the city no longer provided child care employees with health insurance, workers compensation, and unemployment insurance, leaving it to the providers to deliver these benefits.

Initially, the program capacity for EarlyLearn was expected to be 41,764, a decrease of more than 7,000 slots from the combined existing capacity of contracted child care and Head Start providers in 2012. While the number of slots was expected to drop, the spending per slot was expected to grow. Thus, the original plan was based on a trade-off between increased quality and decreased quantity. (See IBO’s March 2014 report for details.)

After complaints from advocates, parents, providers, and elected officials about the impending reduction in contracted capacity, the Bloomberg Administration added funding for 4,147 slots and the City Council funded another 4,919 slots. Therefore, as of the 2013 Adopted Budget the expected number of contracted slots had risen to 50,830, an increase of 1,859 slots compared with the capacity in 2012.

There were important differences between the child care slots funded by the Council and those funded by the Bloomberg Administration, however. Unlike the EarlyLearn slots, these City Council child care slots were originally funded for just one year. Moreover, the contracts funded by the City Council were not issued under the terms of EarlyLearn, providers were chosen by the Council rather than ACS, and ACS did not count them as part of its EarlyLearn system.

Impact on Enrollment. The first four years of the EarlyLearn program have coincided with a considerable decrease in contracted enrollment, although some of this decrease would have occurred even if the city had not introduced EarlyLearn; in particular, the shift of thousands of ACS Head Start slots previously administered by the city to independent providers accounts for some of the decline.

In the years prior to the implementation of EarlyLearn, the city’s subsidized child care system had shrunk considerably, as city funding cuts, a leveling off of federal funds and rising provider costs led ACS to cut back on capacity. Average child care enrollment decreased steadily from an all-time peak of 116,355 in fiscal year 2006 to 95,977 in 2012. Enrollment in Head Start, however, held relatively constant at around 18,000.

The new EarlyLearn contracts began to be implemented in October 2012 (fiscal year 2013). As intended, EarlyLearn has had no substantial impact on the number of children receiving child care vouchers, which decreased only slightly from 69,018 in 2012 to 67,420 in 2016. While vouchers for low-income working families decreased by 4,579 over this period, this was partially offset by an increase in the use of vouchers by families receiving public assistance

On the other hand, there was a large decrease in contracted child care enrollment. Total enrollment in ACS contracted center-based and family care shrank by 12,623, from 43,293 in 2012 to 30,670 in 2016. Taking into account the relatively small number of City Council contracted child care slots that remained in 2016 does not appreciably change the magnitude of the decline.

Most of the decrease in contracted enrollment is a result of a decrease in capacity. As noted previously, when the 2013 budget was adopted, contracted capacity was expected to total 50,830, including 45,911 ACS slots (the 41,764 initially proposed by the Administration and the 4,147 added at budget adoption) and 4,919 City Council slots. This would have been an increase of 1,859 slots from 2012. By 2016, however, actual capacity was just 38,309 ACS slots and 734 City Council slots.

Part of the decline was due to an unanticipated shift in Head Start capacity from the city to independent providers as a result of the federal decision to implement a new round of grant competition, allowing private providers to compete with the city to provide Head Start slots. Although the slots awarded to private providers now fall outside of city control, they remain available to New York City families. This new round of federal competition decreased the number of city-provided EarlyLearn Head Start slots by about 6,500.

In addition, in the four years since EarlyLearn began, some providers have withdrawn slots due to problems in implementation, such as difficulties with hiring staff or achieving enrollment goals. Most recently, a new round of contracting designed to incorporate most of the City Council slots into the EarlyLearn system awarded about 4,200 slots beginning in 2016. Implementation problems, however, caused providers to relinquish about 1,600 of these new EarlyLearn slots, so that capacity once again fell in 2016. ACS reports that it has since reallocated the 1,600 relinquished seats.

Beyond the decreases in capacity, many EarlyLearn providers continue to have difficulty achieving full enrollment. The implementation of EarlyLearn contracts led to disruptions for many families as long-established providers were replaced in some neighborhoods, leaving the families without connections to the replacement contractors. In addition, EarlyLearn providers face continued competition from child care vouchers, which many families find more flexible in meeting their child care needs. ACS has responded to the enrollment challenges facing EarlyLearn providers by increasing technical assistance for recruiting new families, providing greater flexibility in the mix of children they could serve, and by revising the EarlyLearn reimbursement system so that payments to contractors are no longer based on actual enrollment. The new reimbursement system—which resembles the pre-EarlyLearn reimbursement model—eliminates some of the financial risk for providers by providing them guaranteed funding tied to their service capacity, rather than their enrollment.

Spending Trends. As expected, the implementation of EarlyLearn has led to a notable increase in spending per child for ACS contracted care, as providers received increased compensation to cover the cost of the additional services they were required to offer. In 2012 average spending per child in contracted child care and Head Start was $13,667.2 By 2016 spending per child enrolled in EarlyLearn had risen to $17,421, an increase of 27.5 percent. Total spending on ACS contracted care, however, fell by 9.7 percent, from $591.7 million to $534.3 million, due to the large reduction in capacity and enrollment. After accounting for the additional $10.7 million in spending on City Council contracted child care, total contracted spending in 2016 reached $545.0 million, which was still 7.9 percent lower than 2012.

In contrast, overall spending on child care vouchers increased by 8.1 percent, from $452.9 million in 2012 to $489.6 million in 2016. This increase was primarily due to spending on vouchers for families on cash assistance, which rose by 7.8 percent from $364.8 million in 2012 to $393.1 million in 2016, driven mainly by an increase in enrollment from 51,780 to 54,761. Spending on vouchers for other low-income families increased by 9.4 percent, from $88.1 million to $96.5 million, in spite of a 26.6 percent decrease in average enrollment from 17,238 to 12,659. The decline in enrollment was offset by a 49 percent rise in spending per child from $5,113 to $7,619, which resulted in part from the phasing out of a low-cost type of after-school voucher.3

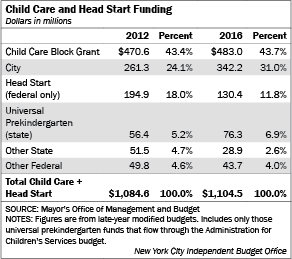

Funding Issues. While the ACS child care system continues to be funded with a variety of revenue streams, there has been a notable change in the funding mix over the last few years. In particular, the program has become more dependent on city funds and state prekindergarten funds while absorbing reductions in federal Head Start grants associated with a shift away from city provision of Head Start.

In 2012 city funds amounted to $261.3 million, or 24.1 percent, of the combined child care and Head Start budget; by 2016 city funds had increased to $342.2 million, or 31.0 percent, of total funding. Much of this increase resulted from discretionary funding added by the City Council beginning in 2013 to increase the number of contracted child care slots beyond those awarded in the original EarlyLearn contracts. In 2016 most of these funds were incorporated into an expanded EarlyLearn system.

Beginning in 2015 the de Blasio Administration started an initiative to sharply increase the availability of full-time prekindergarten classes for the city’s 4-year-olds, using expanded state funding. As part of this effort, funds were added to the ACS budget to upgrade prekindergarten services at EarlyLearn centers. As a result, state prekindergarten funds increased from $56.4 million in 2012 to $76.3 million in 2016. This has been more than offset, however, by the reduction in Head Start funds available to the city over this same period, from $194.9 million to $130.4 million, as a result of the federal competition that shifted some Head Start programs—and funding—from the city to independent providers.

Finally, the Child Care Block Grant (CCBG) — which consists of a blend of federal Child Care and Development Block Grant funds, federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) funds, and state funds — remains the largest source of child care funds. CCBG funds increased modestly from $470.6 million in 2012 to $483.0 million in 2016, and this funding stream continues to account for about 43 percent of the city’s child care and Head Start budget.

The city’s child care system could be facing new funding needs in the near future. While the recent decision by the de Blasio Administration to reimburse EarlyLearn contractors based on capacity rather than enrollment is expected to improve the finances of many providers, other challenges remain. In September 2016, members of the union representing EarlyLearn child care workers approved an agreement with the Day Care Council of New York that uses city funds to substantially increase staff salaries over the next four years. Another part of the agreement, also being funded by the city, provides more affordable health care benefits through MetroPlus, a health insurance plan administered by NYC Health + Hospitals—a reversal of the previous policy under EarlyLearn. When EarlyLearn was first implemented, the city moved away from directly providing health insurance to child care workers, shifting this responsibility to the contractors and their workers, who were—for the first time—required to pay insurance premiums. The new agreement to provide benefits through MetroPlus is expected to substantially reduce child care worker’s cost of coverage.

Nevertheless, even with this agreement, there will continue to be notable pay disparities between the various categories of EarlyLearn teachers and their counterparts at the Department of Education. The expansion of universal prekindergarten has further highlighted these pay disparities. As a result many contractors are having difficulty retaining teachers, who have a strong incentive to move to higher paying positions at DOE. The competition for teachers will likely intensify as the de Blasio Administration rolls out its new preschool program for 3-year-olds. Resolving these disparities could require a substantial commitment of new funds.

In meeting these challenges, it is unlikely that the city will have access to substantial amounts of new state or federal funds. The federal TANF block grant remains frozen at its original 1996 level. In November 2014, Congress reauthorized the Child Care and Development Block Grant but did not add new funds. In addition, the federal legislation contained a number of new health and safety requirements including background clearances, licensing and regulatory compliance, and training and professional development. Meeting these requirements is expected to cost New York State hundreds of millions of dollars over the next few years. While the state has announced that it has applied for a waiver to delay implementation of these new procedures, it will eventually need to allocate funds to comply with the new regulations. This new need could further complicate efforts to increase the CCBG subsidies that are awarded to New York City and other localities.

Expanding Alternatives to Child Care

Over the past decade the city has increased the availability of programs for children that can serve as alternatives to traditional child care for some families. Specifically, city officials have greatly expanded after-school programs for school-age children, and prekindergarten programs for 4-year-olds.

After-School Programs. In his 2004 Executive Budget, as part of a larger plan to streamline social services, Mayor Bloomberg proposed to transfer after-school child care services that were then delivered by ACS to the Department of Youth and Community Development (DYCD). To accomplish this, the Bloomberg Administration proposed vastly expanding after-school programs at DYCD by creating a new program to be called Out-of-School Time (OST). The first OST programs began operating in the fall of 2005. Although OST included programs for middle school and high school students, it was primarily the elementary school programs that were intended to replace ACS school-age child care. Enrollment in OST elementary school-year programs reached 20,308 in 2006, the first year of operation, and grew steadily to 45,384 in 2009. After that point enrollment growth slowed, reaching 49,264 in 2016. (In 2015, OST was renamed Comprehensive After School System of New York City or COMPASS NYC.)

As intended, the growth in DYCD after-school programs coincided with a steady reduction in the use of ACS child care programs serving school-age children from low-income families, with average enrollment decreasing from 19,906 in 2006 to 7,938 in 2014. Since then, however, ACS enrollment has leveled off at 7,528 in 2015 and 7,565 in 2016.

It now appears that the Bloomberg Administration’s original plan of transferring virtually all low-income children from ACS school-age child care to DYCD after-school programs is not likely to be achieved. When the OST system was created, ACS gave vouchers to parents of children in school-age child care who were not able to find an appropriate OST program for their children near their homes. The vouchers allowed the children to remain in ACS programs. Over time, ACS continued to provide vouchers to families whose children aged out of preschool child care and were unable to find a comparable OST program near them. In addition to these Mayoral-funded vouchers, each year the City Council has added funds for school-age vouchers as part of the adopted budget. More recently, Mayor de Blasio expressed support for a continuing school-age child care program at ACS.

Moreover, further reductions in ACS school-age enrollment could require an expansion of DYCD’s after-school programs for elementary school students. Although the de Blasio Administration has greatly expanded after-school programs, the emphasis has thus far been on after-school for middle school students. In September 2014, a new initiative known as School’s Out New York, or SONYC, more than tripled the number of after-school slots available to middle school students.

Finally, it should be emphasized that the original plan to reduce the use of child care vouchers by expanding after-school programs made no mention of cash assistance families using vouchers for school-age child care. The increased availability of after-school services administered by DYCD does not seem to have had a substantial impact on the child care decisions made by these families; the number of cash assistance families using vouchers for school-age child care increased from 24,039 in 2007 to 25,077 in 2016.

Universal Prekindergarten. As the de Blasio Administration moved to greatly expand the number of full-day prekindergarten slots available for the city’s children, many expected that there would be a corresponding decline in the use of child care vouchers for 4-year-olds. Thus far, however, the pre-k expansion has had only a limited impact on the ACS child care system.

As a result of the Mayor’s initiative, the total number of children enrolled in the city’s prekindergarten programs increased by 28.9 percent from 55,734 in October 2013 to 71,845 in October 2015. Aside from creating new slots, the initiative emphasized the conversion of half-day pre-k programs to full-day programs. Consequently, full-day enrollment more than tripled, rising from 19,490 to 69,090 over this two-year period.

The widespread availability of full-day prekindergarten services provided a potential alternative to full-time child care vouchers for many families with 4-year olds. Children enrolled in contracted EarlyLearn programs were already receiving full-day care, including a prekindergarten session, although many of these pre-k classes required upgrading to bring them up to the educational standards of the de Blasio Administration’s expanded prekindergarten program. The expansion of full-day prekindergarten was expected to have a greater impact on families using full-time vouchers for child care. These families had been making use of a wide variety of child care providers of widely varying quality. It thus seemed likely that the educational benefits provided by the city’s prekindergarten programs would lead many of these voucher families to shift their children into pre-k classes.

So far, however, the expansion of full-day pre-k has been accompanied by only a modest decrease in the use of full-time child care vouchers for 4-year-olds. For children in low-income families, the number of vouchers for full-time care fell by 23.3 percent, from 1,395 in school year 2013-2014 to 1,070 in 2015-2016. For the children of cash assistance families the decrease was only 9.5 percent, from 6,128 to 5,549. Together, these changes mean that as of fall 2015, 6,619 4-year-old children were still in voucher-funded full-time child care rather than Department of Education pre-k classes. The relatively small number of 4-year-olds in part-time voucher child care increased over the two years by 36.9 percent, from 279 to 382. It is possible that many of them were attending pre-k classes and using the vouchers for after-school care. Preliminary evidence from fall 2016 indicates that this pattern has not substantially changed.

Future Challenges

Over the last several years ACS has implemented the EarlyLearn initiative, designed to standardize and improve the quality of its contracted child care, while maintaining an extensive system of child care vouchers for low-income and cash assistance families. At the same time the city has increased the availability of programs that can serve as alternatives to traditional child care, including after-school programs for school-age children and prekindergarten programs for 4-year-olds. The Mayor’s 3-K for All initiative would add to those alternatives to traditional child care.

Taken together, these changes have expanded the program options available to many working parents with young children. The city, however, faces a number of challenges in maintaining and improving these services in the years ahead. The challenges may grow as the city moves to shift the management of EarlyLearn from ACS to DOE.

Four years after its inception, EarlyLearn continues to experience some important glitches. In some instances child care providers that were awarded contracts had to withdraw seats due to difficulties in implementation, decreasing overall capacity by thousands of slots. In addition, many providers are still having difficulty achieving full enrollment; the ratio of enrollment to capacity in the contracted child care system is still lower than it was in the year before the start of EarlyLearn. Finally, many contractors have had difficulty recruiting and retaining qualified staff due to the relatively low salaries they are able to offer compared with salaries paid by the city’s Department of Education. An open question regarding the shift of EarlyLearn to DOE is what impact the move will have on contractor salaries.

Another challenge stems from the changing composition of the child care population. Since 2012 there has been a substantial reduction in both contracted child care enrollment and in the number of children using low-income vouchers. The use of child care vouchers by cash assistance families, however, has increased. As a result, by 2016 the majority (55.5 percent) of the children enrolled in the city’s child care system were using cash assistance child care vouchers. This group has proven especially reluctant to participate in the contracted EarlyLearn system as well as the expanded DYCD after-school programs. Most notably, cash assistance families have been slow to embrace the increased availability of prekindergarten classes in spite of an extensive outreach effort by the city. As of the fall of 2015, there were 5,549 4-year-olds from cash assistance families still using full-time child care vouchers instead of attending pre-k classes. Although this was a decrease of 9.5 percent from the 2013-2014 school year, overall full-day prekindergarten enrollment more than tripled over the same period.

The reluctance to make use of the educational benefits offered in pre-k classes could leave many of the city’s poorest children at an academic disadvantage relative to their peers. Parents who use child care vouchers can choose among a wide variety of child care providers including informal care, family child care, and center-based care. As of October 2015, about two-thirds of cash assistance voucher children were enrolled in either informal care or family care programs. These children were unlikely to be receiving the structured educational experience available to children enrolled in the Department of Education’s pre-k programs. It is possible that many cash assistance families prefer the more flexible and longer hours and year-round coverage offered by child care vouchers, particularly families whose work or training hours extend beyond the school day or those with irregular work schedules. The development of after-school programs for 4-year-olds in pre-k classes might entice more of these families to enroll their children in the DOE classes.

Meeting these challenges is likely to require additional spending, even without implementing the Mayor’s 3-K for All initiative. In Washington, the Trump Administration has proposed significant reductions in domestic spending, which could result in funding reductions to a number of state and city programs. Since it is unlikely that the city will have access to substantial amounts of new state or federal child care funds, efforts to address some of these remaining challenges in the current programs will likely require the city to devote more of its own resources to improving its child care and early education programs. The initial 3-K for All program, which covers only two of the 32 community school districts in the city in the first year and eight eight by the fall of 2020, will be entirely city funded, but the Mayor has said he would need state and/or federal funds to scale it up to cover the full city. Thus, the expansion of 3-K for All might compete for state and federal funds that could also be used to address the challenges that remain for the current programs.

Prepared by Paul Lopatto

ENDNOTES

1The income threshold for eligibility for subsidized child care varies with the size of the family, and copayments increase with income. As of September 2015, a family of three would be eligible for subsidized care if their monthly gross income was below $4,270, but at that income level they would be required to make a weekly copayment of $167 for full-time child care.

2All of the spending numbers in this section exclude direct personal services costs at ACS, such as the salaries of ACS staff who administer the child care program.

3In 2012, in an effort to maximize the number of after-school vouchers, the Mayor and City Council agreed to reduce the value of some vouchers to $2,748. When this limit made it difficult for many parents to find after-school providers, the low-cost vouchers were gradually phased out, raising the average cost of low-income vouchers.