January 2014

Staying or Going?

Comparing Student Attrition Rates at

Charter Schools with Nearby Traditional Public Schools

PDF version available here.

January 2014

Staying or Going?

Comparing Student Attrition Rates at

Charter Schools with Nearby Traditional Public Schools

PDF version available here.

Summary

One of the major issues in the debate over the expansion of charter

schools in New York City has been the question of whether students

transfer out of charter schools at higher rates than at traditional

public schools. Researchers have found that changing schools can

affect achievement and that for minority and disadvantaged students

who change schools frequently it may be a contributor to the

achievement gap.

To assess whether elementary grade students in charter schools leave

their schools any more frequently than students in traditional

public schools, IBO examined a cohort of students who entered

kindergarten in September 2008 and followed them through third

grade. This involved tracking data on 3,043 students in 53 charter

schools and 7,208 students in 116 traditional public schools nearest

to each charter.

We compared the rate at which charter school students in this cohort

left their kindergarten school with the rate at which those in the

same cohort in neighboring traditional public elementary schools

left their schools. In addition to comparing the overall rates for

the schools, we also consider any differences in rates based on such

student characteristics as gender and race/ethnicity as well as

poverty, special education, or English language learner status.

Among our findings:

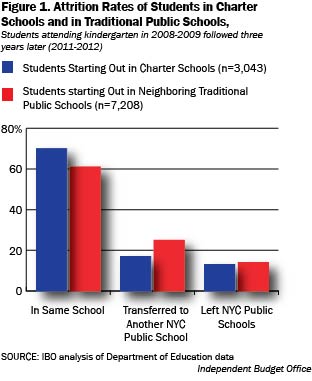

On average, students at charter schools stay at their schools at a

higher rate than students at nearby traditional public schools. About

70 percent of students attending charter schools in school year

2008-2009 remained in the same school three years later, compared

with 61 percent of students attending nearby traditional public

schools three years later.

This higher rate of staying at charter schools also is found when

students are compared in terms of gender,race/ethnicity, poverty,

and English learner status.

The

one major exception is special education students, who leave charter

schools at a much higher rate than either general education students

in charter schools or special education students in traditional

public schools. Only 20 percent of students classified as requiring

special education services who started kindergarten in charter

schools remained in the same school after three years.

We also found that for both charter school and traditional public

school students, those who stayed in the same school from

kindergarten through third grade did better on standardized math and

reading tests in third grade than students from the cohort who

switched schools. The achievement gap between stayers and movers was

considerably larger for those who left charter schools and the gap

was larger in math than reading.

How likely are students to leave New York City’s

charter schools? This schools brief compares attrition rates for

students attending charter schools in early elementary grades to

those of students attending nearby traditional public schools. Our

analysis includes all students enrolled at charter schools in

kindergarten in school year 2008-2009, creates a comparison sample

of students attending neighboring traditional public schools, and

follows both groups of students over the next three years. This

allows us to compare the students who move out of charter schools to

students who continue at their original charter schools and to

students in neighboring traditional public schools. In addition to

documenting the overall trends, this brief disaggregates attrition

rates by student characteristics—demographics including gender and

race, special needs status (special education students and English

language learners), and subsequent achievement.

Mobility is an important determinant of student achievement.

Researchers agree that student achievement suffers when children and

families move, and the higher incidence of migration for minority

and disadvantaged students has been suggested as a contributor to

the achievement gaps.1 But evidence on whether charter

school students experience greater mobility than students in

traditional public schools is mixed, with some researchers finding a

higher rate of attrition for charter school students and others

finding no significant difference.2

Over the last 10 years, cities such as New York

City, Boston, Chicago, and Washington DC have encouraged and

supported the growth of charter schools. However, even though

charter schools have become an integral part of New York City’s

changing education landscape, there has been little research about

the mobility of students attending these schools. This brief throws considerable light on the following questions:

1.

What

are the rates of attrition from charter schools in New York City

that serve elementary grades (kindergarten through third?

2.

Of

those students who leave charters, do more transfer to another

charter school in the city, or to a New York City traditional

public school, or leave the city’s public sector schools altogether?

3.

How

do the attrition rates for charter schools compare with those of

students attending neighboring traditional public schools?

4.

How

do these rates compare across the three grades?

5.

How

do these rates differ by student characteristics, including gender

and race of the student, English language learner status and special

education status, and performance on tests of English Language Arts

and mathematics?

6.

Is

there any evidence for selective attrition, particularly with

respect to specific student characteristics or student achievement?

Do the data show that low-achieving students, as measured by future

test scores, are the ones to leave charter schools?

Sample and Data

This brief includes all students attending kindergarten in 2008-2009

in a New York City charter school that served the elementary grades.

Since students can change schools during the year, this brief uses

the start date of classes—September 2, 2008 for the

2008-2009 school year—to assign students to schools. Thus, a charter

school student included in this sample is one who was registered at

a New York City charter school in kindergarten as of September 2,

2008. The same rule is applied to students attending neighboring

traditional public schools in our comparison group.

The comparison group of traditional public school students, against

whom this brief matches up the attrition rates of charter school

students, is defined as follows. Since charter schools enroll a

small part of the city’s K-12 student population and are not

uniformly distributed geographically across the city, this brief

only includes those traditional public schools that are located

close to a charter school. The underlying assumption is that if the

charter school in question had not been established, then children

in the vicinity would most probably have enrolled in the nearby

traditional public school.3 Thus, students attending a

neighboring traditional public school should constitute an

appropriate comparison group for students currently attending a

charter school. This assumption is bolstered because charters often

use a geographic criterion, including geographically limited

lotteries, for admission. Under New York State law, students

residing nearby are given priority—ensuring most students are drawn

from the neighborhood in which the charter school is located.4

For practical implementation, this brief identifies the three

nearest traditional public schools for every charter school;

students attending these traditional public schools make up the

comparison group for charter school students.5

Not all schools offer the same array of grades—this is true for both

charter and traditional public schools—and therefore this brief

restricts the sample to only those which had first grade in

2009-2010, second grade in 2010-2011 and third grade in 2011-2012.

This is to ensure that the mobility patterns which are observed are

not the result of students transferring out due to being in their

school’s terminal grade. This brief also drops the few schools which

had less than 10 students in kindergarten. The final sample for

charter school students has 53 schools and 3,043 students, whereas

the corresponding sample for students in nearby traditional public

schools has 116 schools and 7,208 students.

This

analysis focuses on the mobility behavior of students comparing

charter school students with their counterparts in nearby

traditional public schools. The year 2008-2009 is chosen as the base

year both because of a desire to focus on more recent experience and

because these students can be followed through to 2011-2012. Most

students in this cohort would have attended third grade

in 2011-2012, when they would take the state-mandated standardized

tests for that grade. Moreover, working with 2008-2009 as the base

year helps us have a much larger sample—53 charter schools and more

than 3,000 charter school students—than we would have if this brief

had started with an earlier cohort.6

Most of the data used in this analysis have been

obtained from the New York City Department of Education (DOE). To

assign students to a particular charter or traditional school as of

September 2, 2008, we combed through the most detailed data

available to us, a file of all student registration transactions

including admissions, discharges, and transfers. Next we used the

DOE’s biographic files to add information on demographic and

academic indicators for each student. For years two and three of the

study the same procedure was followed: in each case, students are

assigned to a school based on their enrollment as of the first day

of classes for that year. For the third year, we also used DOE’s

achievement files.

Data on the names, addresses, and grade spans

both of charter schools and traditional public schools have also

been extracted from files obtained from the DOE. These files contain

information on the exact geographic location of each school

(latitude and longitude, x and y coordinates).7 These

data were used to find traditional public schools closest to each

charter school based on distance—the distances were in radian

units—and we selected the three closest schools to form the

comparison group in the study.

Methodology

The section begins with a detailed discussion of how this brief defines mobility. It then looks at how students in charter schools differ from their counterparts at traditional public schools in order to identify other differences—apart from the two types of schools—that could influence attrition. Note that this brief is concerned with the rates of student exit prior to the end of the range of grades that their school serves.

Defining Mobility.

Students were assigned to schools as of the first day of class

during the respective year, which was September 2 for the 2008-2009

school year; September 9 for the 2009-2010 year; September 8 for the

2010-2011 year; and September 8 for the 2011-2012 year. Thus, a

student is recorded as continuing in the same school in 2009-2010 if

she is attending the same school on September 9, 2009 as on

September 2, 2008; and so on. Conversely, she is deemed to have

transferred to another New York City public school in

2009-2010—either another charter school or a traditional public

school—if the records show her in a different school as of September

9, 2009. The student is considered to have left the city’s public

schools if she does not appear in any public school records as of

the start date of classes in that particular year.

This brief focuses on the cumulative incidence of attrition between kindergarten and the following three years. It analyzes whether a student who was enrolled in a school as of the first day of classes during 2008-2009 (September 2, 2008) leaves that school during the following three years, so that she is not enrolled there on the first day of classes during 2011-2012 (September 8, 2011). However, the brief also reports the annual attrition rates between 2008-2009 and 2009-2010, between 2009-2010 and 2010-2011, and between 2010-2011 and 2011-2012 (see Table 3).

Comparing Students at Charter and

Traditional Public Schools.

Before proceeding to a detailed analysis of attrition rates, it is

useful to briefly compare the kindergarten students who entered

charter schools in 2008-2009 with kindergarteners entering

neighboring traditional public schools that same year (Table 1).

There is little difference in terms of gender composition. However,

charters serve a much higher percentage of black students, while

traditional public schools serve a much higher share of Hispanic

students.8 The share of Asian students in charter schools is very low relative to

the share in neighboring traditional public schools, although the

numbers involved are fairly small. Based on eligibility for free or

reduced-price lunches, the shares of low-income students seem to be

similar in the two types of schools (a little less than

three-quarters). However, a much higher share of students in

traditional public schools are missing these forms or have

incomplete ones—and paying full-prices for lunch because of

that—suggesting perhaps that charter schools do a better job of

enforcing paperwork requirements. Only considering students whose

lunch-eligibility forms are complete, a larger share of students at

nearby traditional public schools come from low-income families.9

|

Table 1. Composition of Students Attending

Kindergarten In 2008-2009

|

||

|

Student

Attributes |

Percentage of Students in Charter Schools |

Percentage of Students in Nearby Traditional

Public Schools |

|

Male |

51.O |

50.4 |

|

Female |

49.0 |

49.6 |

|

White Students |

4.2 |

8.8 |

|

Black Students |

61.1 |

33.3 |

|

Hispanic Students |

26.7 |

47.8 |

|

Asian Students |

1.7 |

7.9 |

|

Other/Not Specified |

6.3 |

2.2 |

|

Students Eligible for Free or Reduced-Price

Lunches, Based On Form |

74.1 |

70.6 |

|

Students Paying Full-Price for Lunch, Based on

Form |

19.5 |

6.8 |

|

Students Paying Full-Price for Lunch, Missing or

Incomplete Form |

6.4 |

22.6 |

|

Special Education Students |

0.8 |

7.0 |

|

English Language

Learner Students |

4.0 |

18.3 |

|

Total Number of Students |

3,043 |

7,208 |

|

SOURCE: IBO analysis of Department of Education

data

Independent Budget

Office |

||

The main differences regarding student composition between charters

and traditional public schools lie in the rates of serving special

education students and English language learner (ELL) students.

About 7 percent of kindergarten students in nearby traditional

public schools are special education students; the share in charter

schools is less than 1 percent. The difference in rates of serving

ELL students is similarly large—18 percent in traditional public

schools compared with 4 percent in charter schools. These

differences have been noted in other studies of charter schools in

New York City. The brief revisits the issue of special education

students later in Figure 2 and Tables 6 and 7.

Incidence of Attrition

Kindergarteners in charter schools exhibit

significantly less mobility during the subsequent three years

relative to their peers in neighboring traditional public schools.

Most of the difference is attributable to attrition in the immediate

post-kindergarten year, and almost all is accounted for by

differences in the rate of switching schools within the New York

City public school system. Only a few students repeat grades, in

either charter schools or nearby traditional public schools. In

terms of destination schools, movers from both charter schools and

traditional public schools in higher grades increasingly transfer to

a traditional public school rather than a charter school. When this

brief looks at various student subgroups, there are significant

differences among students in traditional public schools, but

relatively less so among students in charter schools. The exception

is special education students in charter schools, who leave their

schools at much higher rates than others.

Of the 3,043 students who were attending

kindergarten in charter schools in 2008-2009, about 70 percent

remained in the same school in 2011-2012, three years later (see

Figure 1). This number is considerably higher than for students

attending kindergarten in neighboring traditional public schools in

2008-2009—only 61 percent of the latter group remained in their

original schools after three years. The difference is almost

entirely due to the difference in the share transferring to another

school within the system; while 17 percent of kindergarteners in

charter schools switched schools later, 25 percent of

kindergarteners in nearby traditional public schools did so. The

share of students leaving the New York City public school system is

almost identical across the two groups.

It is

instructive to look at the grade distribution of 2008-2009

kindergarteners who remained in either the city’s traditional public

schools or charter schools in 2011-2012 (table 2). Not surprisingly,

the overwhelming majority were attending grade 3, as they would have

if they progressed at the usual rate. About 10 percent of both

charter and traditional public school students were attending grade

2 due to repeating a grade earlier. In addition, there were a few

2008-2009 kindergarteners who skipped a grade and were attending

grade 4 in 2011-2012. Although it was more common for charter school

students to skip a grade, the number of students who did so was too

small to draw any substantive conclusions.

|

Table 2. Grade

Distribution of 2008-2009 Kindergarteners After Three Years,

in 2011-2012 |

||||

|

|

Students Starting Out In Charter Schools |

Students Starting Out In Nearby Traditional Public Schools |

||

|

Number |

Percentage |

Number |

Percentage |

|

|

Grade 1 |

4 |

0.1 |

21 |

0.3 |

|

Grade 2 |

297 |

9.8 |

771 |

10.7 |

|

Grade 3 |

2,323 |

76.3 |

5,424 |

75.2 |

|

Grade 4 |

43 |

1.4 |

8 |

0.1 |

|

Total Students Matched in

2011-2012 |

2,667 |

87.6 |

6,224 |

86.3 |

|

Left New York City Public Schools |

376 |

12.4 |

984 |

13.7 |

|

Total Students Starting Kindergarten in 2008-2009 |

3,043 |

100 |

7,208 |

100 |

|

SOURCE: IBO analysis of Department of Education data

NOTE: The sample includes only those students who could be

matched in 2011-2012 as enrolled in New York City Public

Schools (either charter or traditional public) as of the

first day of classes (September 8, 2011). Those who left New

York City public schools are not included.

Independent Budget

Office |

||||

Attrition During Intervening Years. Of students who were attending kindergarten in charter schools in 2008-2009, about 85 percent remained in the same school the next year (2009-2010). This is shown in Table 3, which reports a more detailed picture of attrition throughout the three intervening years, disaggregating students’ mobility status as of the first day of classes during each intervening year (September 9, 2009; September 8, 2010; and September 8, 2011). This figure is 9 percentage points higher than the corresponding figure for students who were attending kindergarten in neighboring traditional public schools. The difference comes both from the rate of transferring to another school within the school system (9 percent for kindergarteners in charter schools versus 14 percent for kindergarteners in traditional public schools) and from the rate of leaving the city’s public schools (6 percent versus 9 percent)

Over a two-year horizon, students originally in

charter schools again have less attrition: 77 percent continue in

their original school, compared with only 67 percent of students who

started out at nearby traditional public schools. However, the

differences seem to have stabilized after the first year, and remain

roughly the same when looking at a three-year horizon. In the next

table (Table 4) this is analyzed further. Students who continued at

their schools are subdivided into those who progressed to the next

grade and those who were repeating the same grade. Students who left

their original schools are disaggregated into those who transferred

to another New York City public school and those who left the

system.

|

Table 3. Mobility Rates as of First Day of Classes,

2009-2010, |

|||

|

|

Percentage as of |

||

|

September 9, 2009 |

September 8, 2010 |

September 8, 2011 |

|

|

Students in

Charter Schools |

|

|

|

|

Same School |

85 |

77 |

70 |

|

Different NYC

Public School |

9 |

14 |

17 |

|

Left NYC Public Schools |

6 |

10 |

12 |

|

Students in Nearby Traditional Public Schools |

|

|

|

|

Same School |

76 |

67 |

61 |

|

Different NYC

Public School |

14 |

20 |

25 |

|

Left NYC Public Schools |

9 |

12 |

14 |

|

SOURCE: IBO analysis of Department of Education data

Independent Budget

Office |

|||

Attrition Disaggregated by Grade

Repetition and Destination. A slightly higher share of

the charter school cohort is repeating kindergarten in 2009-2010 as

compared with the traditional public school cohort, though the share

is small in both groups (Table 4). Among movers from charter

schools, about the same share transfers to another charter school,

compared with movers from nearby traditional public schools. Across

the years, these same patterns prevail—in higher grades, however,

movers from both charter schools and traditional public schools

increasingly transfer to a traditional public school rather than a

charter school. The increased incidence of transfer to a traditional

public school, instead of a charter school, might be due to the fact

that many charters limit admissions to traditional starting points

(such as kindergarten for elementary schools).

|

Table 4. Attrition Status of Students Attending Kindergarten in

2008-2009, Followed Over the Next Three Years |

||||

|

Attrition Status in Various Years |

Students in Charter Schools |

Students in Nearby Traditional Public Schools |

||

|

Number |

Percentage |

Number |

Percentage |

|

|

Students in Grade Kindergarten |

3,043 |

100 |

7,208 |

100 |

|

Status as of September 9, 2009 |

|

|

|

|

|

Same School |

2,584 |

85 |

5,491 |

76 |

|

Progressed to Next Grade |

2,500 |

82 |

5,379 |

75 |

|

Repeating Same Grade |

84 |

3 |

112 |

2 |

|

Different NYC Public School |

272 |

9 |

1,043 |

14 |

|

Traditional Public School |

194 |

6 |

785 |

11 |

|

Charter School |

78 |

3 |

258 |

4 |

|

Left NYC Public Schools |

187 |

6 |

674 |

9 |

|

Status as of September 8, 2010 |

|

|

|

|

|

Same School |

2,340 |

77 |

4,846 |

67 |

|

Progressed to Next Grade |

2,257 |

74 |

4,585 |

64 |

|

Repeating Same Grade |

83 |

3 |

261 |

4 |

|

Different NYC Public School |

411 |

14 |

1,474 |

20 |

|

Traditional Public School |

312 |

10 |

1,159 |

16 |

|

Charter School |

99 |

3 |

315 |

4 |

|

Left NYC Public Schools |

292 |

10 |

888 |

12 |

|

Status as of September 8, 2011 |

|

|

|

|

|

Same School |

2,131 |

70 |

4,414 |

61 |

|

Progressed to Next Grade |

2,040 |

67 |

4,257 |

59 |

|

Repeating Same Grade |

91 |

3 |

157 |

2 |

|

Different NYC Public School |

525 |

17 |

1,810 |

25 |

|

Traditional Public School |

397 |

13 |

1,457 |

20 |

|

Charter School |

128 |

4 |

353 |

5 |

|

Left NYC Public Schools |

387 |

13 |

984 |

14 |

|

SOURCE:

IBO analysis of Department of Education data

Independent Budget Office |

||||

Attrition and DemographicsThere

is little difference in attrition rates by student subgroups among

students in charter schools, except for special education students.

This is in contrast to the results for their peers in neighboring

traditional schools, for whom significant differences are evident.

The following subgroups are compared: male students, female

students, white students, black students, Hispanic students,

students eligible for free or reduced-price lunches (based on

completed form), students paying full price for lunch (based on

completed form), special education students, and English language

learner students. The

results are reported as per the original three-way classification of

turnover—distinguishing between those who continued in their current

schools, those who transferred to another New York City public

school and those who quit the New York City public schools. The

detailed results are presented in Table 5.

Among students in the charter school cohort, the

rates of attrition are often very similar across most subgroups. For

example, male students, female students, black students, Hispanic

students, students eligible for free or reduced-price lunches and

ELL students—each of these subgroups all had about the same 70

percent probability of continuing in their original (charter) school

after three years. The exception is special education students.

There is more divergence within the traditional public school

cohort, particularly when disaggregated by race/ethnicity—for

example, 73 percent of white students remained at the same school

after three years, compared with 63 percent of Hispanics and only 53

percent of blacks.

|

Table 5. Attrition Status of Various Subgroups of Students |

||||

|

Attrition Status in Various Years |

Students in Charter Schools |

Students in Nearby Traditional Public schools |

||

|

Male Students |

|

|

||

|

Students in Kindergarten (September 2, 2008) |

1,551 |

3,632 |

||

|

Same School (%) |

69 |

61 |

||

|

Different NYC Public School (%) |

18 |

26 |

||

|

Left NYC Public Schools (%) |

13 |

13 |

||

|

Female Students |

|

|

||

|

Students in Kindergarten (September 2, 2008) |

1,492 |

3,576 |

||

|

Same School (%) |

71 |

62 |

||

|

Different NYC Public School (%) |

17 |

24 |

||

|

Left NYC Public Schools (%) |

12 |

14 |

||

|

White Students |

|

|

||

|

Students in Kindergarten (September 2, 2008) |

127 |

631 |

||

|

Same School (%) |

75 |

73 |

||

|

Different NYC Public School (%) |

15 |

15 |

||

|

Left NYC Public Schools (%) |

10 |

13 |

||

|

Black Students |

|

|

||

|

Students in Kindergarten (September 2, 2008) |

1,860 |

2,397 |

||

|

Same School (%) |

70 |

53 |

||

|

Different NYC Public School (%) |

16 |

32 |

||

|

Left NYC Public Schools (%) |

13 |

15 |

||

|

Hispanic Students |

|

|

||

|

Students in Kindergarten (September 2, 2008) |

811 |

3,449 |

||

|

Same School (%) |

68 |

63 |

||

|

Different NYC Public School (%) |

20 |

24 |

||

|

Left NYC Public Schools (%) |

12 |

13 |

||

|

Students Eligible for Free or Reduced-Price Lunch, Based on

Completed Form |

|

|

||

|

Students in Kindergarten (September 2, 2008) |

2,255 |

5,092 |

||

|

Same School (%) |

70 |

58 |

||

|

Different NYC Public School (%) |

18 |

29 |

||

|

Left NYC Public Schools (%) |

12 |

13 |

||

|

Students Paying Full-Price for Lunch, Based on Completed

Form |

|

|

||

|

Students in Kindergarten (Sep 2, 2008) |

594 |

490 |

||

|

Same School (%) |

76 |

66 |

||

|

Different NYC Public School (%) |

13 |

20 |

||

|

Left NYC Public Schools (%) |

12 |

14 |

||

|

Special Education Students |

|

|

||

|

Students in Kindergarten (September 2, 2008) |

25 |

503 |

||

|

Same School (%) |

20 |

50 |

||

|

Different NYC Public School (%) |

72 |

36 |

||

|

Left NYC Public Schools (%) |

8 |

14 |

||

|

English Language Learner Students |

|

|

||

|

Students in Kindergarten (September 2, 2008) |

123 |

1,316 |

||

|

Same School (%) |

72 |

67 |

||

|

Different NYC Public School (%) |

16 |

21 |

||

|

Left NYC Public Schools (%) |

11 |

12 |

||

|

SOURCE: IBO analysis of Department of Education data

Independent Budget Office |

||||

A Closer Look at Students with Special Needs. The issue

of serving an adequate number of special education students often

crops up in discussions about charter schools. In kindergarten, the

incidence of special needs in charter schools was about one-seventh

of that in traditional public schools. There is a big jump in

classification rates during the first grade, particularly in charter

schools. After first grade, however, the rates of classification

come down—both in charter schools and in nearby traditional public

schools. By third grade, the incidence of special needs is 13

percent for students starting out in charters and 19 percent for

students starting out in nearby traditional public schools,

irrespective of the type of (New York City public) school the

individual student attended that year. The attrition rates are

higher for special education students who start kindergarten in

charter schools than for special education students who start in

neighboring traditional public schools.

Only 20 percent of students classified as requiring special

education who started kindergarten in charter schools remained in

the same school after three years, with the vast majority

transferring to another New York City public school (see Table 5).

The corresponding persistence rate for students in nearby

traditional public schools is 50 percent.

To capture differences in attrition of special

education students across charters and traditional public schools,

this brief follows these students over time, as they progress

through school from kindergarten to third grade. After three years,

out of the 2,656 students who started in charter schools in

September 2008 and are still attending the city’s public sector

schools—either the same charter school (2,131) or another New York

City public school (525)—344 students overall, or 13 percent, had

been classified as special education students. 11,12 Of

those continuing in the same charter school, 10 percent were

identified as special education students by the third year, and of

those transferring out to another charter school, 16 percent were

special education students (see Figure 2). But of those transferring

out to another traditional public school, fully 27 percent were

classified as special education students.

|

Table 6. Classification of Students in Special Education as They

Progress Through School, Kindergarten Through Third Grade |

||||||||

|

Attrition Status in Various Years |

Students in Charter Schools |

Students in Nearby Traditional Public Schools |

||||||

|

Total Students |

Percentage |

Students in Special Education |

Percentage |

Total Students |

Percentage |

Students in Special Education |

Percentage |

|

|

Students in Kindergarten |

3,043 |

100 |

25 |

1 |

7,208 |

100 |

505 |

7 |

|

Status as of September 9, 2009 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Same

School |

2,584 |

85 |

22 |

1 |

5,491 |

76 |

408 |

7 |

|

Progressed to Next Grade |

2,500 |

82 |

21 |

1 |

5,379 |

75 |

383 |

7 |

|

Repeating Same Grade |

84 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

112 |

2 |

25 |

22 |

|

Different NYC Public School |

272 |

9 |

25 |

9 |

1,043 |

14 |

153 |

15 |

|

Traditional Public School |

194 |

6 |

25 |

13 |

785 |

11 |

151 |

19 |

|

Another

Charter School |

78 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

258 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

|

Left

NYC Public Schools |

187 |

6 |

---- |

---- |

674 |

9 |

---- |

---- |

|

Status as of September 8, 2010 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Same

School |

2,340 |

77 |

244 |

10 |

4,846 |

67 |

691 |

14 |

|

Progressed to Next Grade |

2,257 |

74 |

213 |

9 |

4,585 |

64 |

624 |

14 |

|

Repeating Same Grade |

83 |

3 |

31 |

37 |

261 |

4 |

67 |

26 |

|

Different NYC Public School |

411 |

14 |

95 |

23 |

1,474 |

20 |

382 |

26 |

|

Traditional Public School |

312 |

10 |

84 |

27 |

1,159 |

16 |

341 |

29 |

|

Another

Charter School |

99 |

3 |

11 |

11 |

315 |

4 |

41 |

13 |

|

Left

NYC Public Schools |

292 |

10 |

---- |

---- |

888 |

12 |

---- |

---- |

|

Status as of September 8, 2011 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Same

School |

2,131 |

70 |

218 |

10 |

4,414 |

61 |

667 |

15 |

|

Progressed to Next Grade |

2,040 |

67 |

183 |

9 |

4,257 |

59 |

624 |

15 |

|

Repeating Same Grade |

91 |

3 |

35 |

38 |

157 |

2 |

43 |

27 |

|

Different NYC Public School |

525 |

17 |

126 |

24 |

1,810 |

25 |

493 |

27 |

|

Traditional Public School |

397 |

13 |

106 |

27 |

1,457 |

20 |

439 |

30 |

|

Another

Charter School |

128 |

4 |

20 |

16 |

353 |

5 |

54 |

15 |

|

Left

NYC Public Schools |

387 |

13 |

---- |

---- |

984 |

14 |

---- |

---- |

|

SOURCE: IBO analysis of Department of Education data

Independent Budget Office |

||||||||

In comparison, out of the 6,224 students who

started out in kindergarten in neighboring traditional public

schools and were still attending the city’s public schools after

three years—4,414 in the same traditional public school and 1,810 in

another New York City public school—1,160 students overall, about 19

percent, had been identified as special education students by the

third year. This is higher than the corresponding share (13 percent)

for students who started out in charter schools. Breaking down the

cohort by attrition status, of those continuing in the same

traditional public school, 15 percent had been identified as needing

special education services. Of those transferring out to another New

York City public school, 30 percent were receiving special education

services—but of those transferring out to a charter school only 15

percent were special education students. This is in line with

results noted above for the charter school cohort and suggests that

special education students, at least once they have been classified

as such, are more likely to attend traditional public schools.

At the start of kindergarten, out of the 3,043

students starting out in charter schools in kindergarten, only 1

percent were labeled as needing special education services—even

after one year, less than 1 percent of students continuing in the

same charter school were labeled as special education (see Table 6).

For students who begin in charter schools, the big jump in special

education status comes between first and second grades—10 percent of

students continuing in the same school were classified as requiring

special education services by the start of second grade.13

To compare the rates at which students are

classified into special education as they progress through school,

this brief follows separately the 3,043 students who started out

kindergarten in charter schools and the 7,208 students who started

out kindergarten in neighboring traditional public schools (Table

7). Initially, there were only 25 special education kindergarteners

in charter schools, as compared with 505 special education

kindergarteners in nearby traditional public schools. After one

year, at the beginning of 2008-2009, among those from the original

charter school cohort of 3,043 students who were still attending the

same charter school, 22 had been classified as special education

students, most of them being newly classified as such during the

previous year (2008-2009).

|

Table 7. Students in Special Education by Attrition and

Classification Status, Kindergarten Through Third Grade |

||

|

|

Students in Charter Schools |

Students in Nearby Traditional Public Schools |

|

Special

Education Students in Kindergarten (as of September 2, 2008)

|

25 |

505 |

|

Status as of September 9, 2009 |

|

|

|

Same School |

22 |

408 |

|

Previously Classified (%) |

18 |

76 |

|

Newly Classified (%) |

82 |

24 |

|

Different NYC Public School |

25 |

153 |

|

Previously Classified (%) |

64 |

75 |

|

Newly Classified (%) |

36 |

25 |

|

Left NYC Public Schools |

---- |

---- |

|

Status as of September 8, 2010 |

|

|

|

Same School |

244 |

691 |

|

Previously Classified (%) |

5 |

48 |

|

Newly Classified (%) |

95 |

52 |

|

Different NYC Public School |

95 |

382 |

|

Previously Classified (%) |

41 |

46 |

|

Newly Classified (%) |

59 |

54 |

|

Left NYC Public Schools |

---- |

---- |

|

Status as of September 8, 2011 |

|

|

|

Same School |

218 |

667 |

|

Previously Classified (%) |

89 |

85 |

|

Newly Classified (%) |

11 |

15 |

|

Different NYC Public School |

126 |

493 |

|

Previously Classified (%) |

88 |

76 |

|

Newly Classified (%) |

12 |

24 |

|

Left NYC Public Schools |

---- |

---- |

|

SOURCE:

IBO analysis of Department of Education data

Independent Budget Office |

||

Over the same time period, among those from the

original traditional public school cohort of 7,208 students who were

still attending the same traditional public school, 408 had been

classified as special education students—here, however, relatively

few were newly classified. There is a big jump in classification

rates during the first grade, particularly in charter schools—the

number of students from the original cohort who were still attending

the same school as of the beginning of 2010-2011 and are classified

as special education students jumps from 25 to 244. After this year,

however, the rates of classification come down—both in charter

schools and in traditional public schools.

To summarize, starting in in kindergarten only 1

percent of students in charter schools were classified as requiring

special education, compared with 7 percent of students in

neighboring traditional public schools. By third grade, the

incidence of students with special needs increased to 13 percent for

students starting out in charters and to 19 percent for students

starting out in traditional public schools. By grade 3, 63 percent

of the 344 special education kids from the charter sample were in

the same school as they started, 6 percent were in another charter,

and 31 percent were in traditional public schools. From the sample

of students who started out in nearby traditional public schools, 57

percent of the 1,160 special education students were in the same

school, 38 percent were in another traditional public school, and 5

percent were in a charter school.

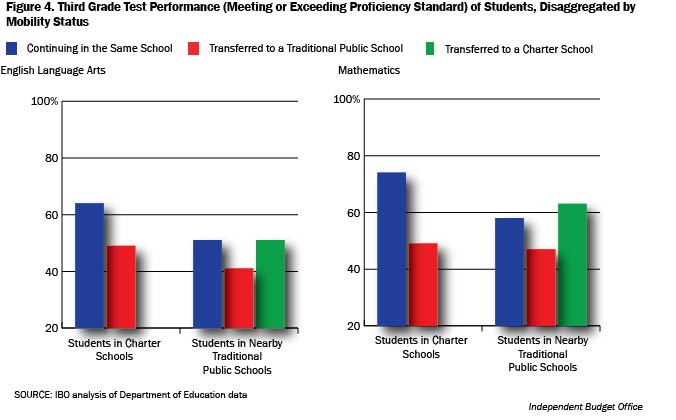

Third Grade Attrition and Test Scores. Students in New York State enrolled in grades 3 through 8 take standardized tests in English language arts and mathematics. Since there is a large literature detailing the deleterious effects of mobility on student performance, holding other things constant, it is instructive to compare the academic performance of students who changed schools (movers) to those of students who remained at their original schools (stayers). These comparisons are given in Table 8 and Figures 3 and 4. Results are shown from the third grade state reading and mathematics tests—in most cases this brief reports results using two measures of achievement: average scale score and whether a student met or exceeded the proficiency standard.14

Note first that in the absence of test score

data on students who left New York City public schools, the

comparison is only between those who stay and those who move to

other city public schools. Second, the tests are given in the spring

of the third year, so most students in our sample would have taken

them in spring 2012. Third, in order to see how students who move

from traditional public schools to charters perform relative to

those who stay or move to a different traditional school, this brief

defines a separate category of students—those among the traditional

public school students who switch to a charter school.

The results are revealing. Among students in

charter schools, those who remained in their kindergarten schools

through third grade had higher average scale scores in both reading

(English Language Arts) and mathematics in third grade compared with

those who had left for another New York City public school (Figure

3). This basic pattern is repeated when looking at the whether

students met or exceeded the proficiency standard (Figure

4)—however, here the gap between stayers and movers is much wider

for mathematics than for reading. Students in traditional public

schools exhibit similar trends to those in charters—a modest but

consistent positive gap in favor of students who are continuing

irrespective of the subject and the particular measure this brief

uses.

One important difference between the two types of schools, particularly manifest when the percentage of students meeting or exceeding proficiency standard is used as the metric, is that the gap between the stayers and movers was significantly larger in charters compared with those in traditional public schools. Also, this gap is larger in mathematics compared with reading. While in reading the gap between stayers and movers is 15 percentage points in charter schools versus 10 percentage points in nearby traditional public schools, the corresponding gap in math is 25 percentage points in charters versus 11 percentage points in nearby traditional public schools (Figure 4 and Table 8).

|

Table 8. Third Grade Test Performance by Students, Disaggregated

by Mobility Status

|

|||

|

|

Students Who Continued at School |

Students Who Transferred to Another NYC Public School |

Students Who Transferred To a Charter School from a

Traditional Public School |

|

Average Scale Scores |

|

|

|

|

English Language Arts |

|

|

|

|

Students in Charter Schools |

667 |

660 |

---- |

|

Students in Nearby Traditional Public Schools |

663 |

658 |

663 |

|

Mathematics |

|

|

|

|

Students in Charter Schools |

694 |

682 |

---- |

|

Students in Nearby Traditional Public Schools |

687 |

683 |

689 |

|

Students Meeting or Exceeding |

|

|

|

|

English Language Arts |

|

|

|

|

Students in Charter Schools |

64% |

49% |

---- |

|

Students in Nearby Traditional Public Schools |

51% |

41% |

51% |

|

Mathematics |

|

|

|

|

Students in Charter Schools |

74% |

49% |

---- |

|

Students in Nearby Traditional Public Schools |

58% |

47% |

63% |

|

SOURCE: IBO analysis of Department of Education data

Independent Budget Office |

|||

|

Table 9a. Attrition Status by Reading Achievement

|

||||

|

Students in Kindergarten As of September 2, 2008 |

Students in Charter Schools |

Students in Nearby Traditional Public Schools |

||

|

Transferred to Another NYC Public School |

Continued at School |

Transferred to Another NYC Public School |

Continued at School |

|

|

Average Proficiency Rating |

2.84 |

3.07 |

2.76 |

2.92 |

|

Average Scale Score |

660 |

667 |

658 |

663 |

|

Distribution of |

|

|

|

|

|

Percent Below Standard |

16% |

5% |

19% |

14% |

|

Percent Meets

|

36% |

31% |

40% |

35% |

|

Percent Meets |

45% |

60% |

38% |

45% |

|

Percent Exceeds |

4% |

4% |

3% |

6% |

|

Number of Students |

416 |

1,848 |

1,415 |

3,893 |

|

Table 9b. Attrition Status by Mathematics Achievement

|

||||

|

Students in Kindergarten As of September 2, 2008 |

Students in Charter Schools |

Students in Nearby Traditional Public Schools |

||

|

Transferred to Another NYC Public School |

Continued at School |

Transferred to Another NYC Public School |

Continued at School |

|

|

Average Proficiency Rating |

2.94 |

3.36 |

2.96 |

3.1 |

|

Average Scale Score |

682 |

694 |

683 |

687 |

|

Distribution of |

|

|

|

|

|

Percent Below Standard |

15% |

3% |

14% |

9% |

|

Percent Meets

|

36% |

23% |

39% |

33% |

|

Percent Meets |

44% |

57% |

38% |

46% |

|

Percent Exceeds |

5% |

17% |

9% |

12% |

|

Number of Students |

419 |

1,848 |

1,419 |

3,895 |

|

SOURCE: IBO analysis of Department of Education data

Independent Budget Office |

||||

There are also intriguing patterns for students who started kindergarten in traditional public schools but then switched to charter schools at some point, so that by the beginning of third grade they were attending a charter school. Generally speaking, those who transferred to a charter school from a traditional public school later performed at a

·

higher

rate compared with their peers from these same traditional public

schools who transferred out (all movers from nearby traditional

public schools)

·

similar, or slightly higher rate, compared with their peers from the

same traditional public schools who stayed in the same school

(stayers in traditional public schools)

·

lower rate compared with the students in charter schools who stayed

in the same school (stayers in charter schools)

·

higher

rate compared with those who transferred out from charter schools,

the difference being small for reading (ELA) but relatively large

for mathematics.

Note, however, that we do not know the applicant

pools for the charter schools, and which students they decide to

admit, in their non-entry grades (after kindergarten). So the above

comparison is purely descriptive, in terms of noting the performance

of students who started kindergarten in neighboring traditional

public schools in 2008-2009 (and are included in our study as such)

but had then transferred to a charter school before the third grade.

The fact that leavers from charter schools have

lower test scores than the stayers suggests that such attrition

serves to increase the overall academic performance of these schools

and might make them more attractive. This might be important if

parents considering where to send their child look more to the

achievement level at the school (particularly average test scores)

than to the degree of improvement in student performance. But, there

are several caveats. First, test scores of those who join a charter

school in non-entry grades, transferring from a traditional public

school in the city, are actually lower than those of the stayers in

charter schools (average scale score of 664 compared with 667)

though higher than the leavers. Thus, if the charters had decided

not to fill up the seats left vacant by transferring-out students,

their average performance would be even higher. Second, the way the

city’s Department of Education assigns letter grades to schools puts

more emphasis on student improvement or progress, rather than on the

absolute levels of performance, it is not obvious that such

selective attrition helps charters attain a better letter grade.

Improving a high-performing student’s test scores is often more

difficult than similar improvements elsewhere, and the Department of

Education gives extra credit for improving student performance at

the lower end of the scale.

Regression Analysis

The comparisons control for different

demographic characteristics of the students, including gender,

poverty, and race/ethnicity, as well as for the number of days the

student was absent. The brief also adjusts for whether a student had

been classified as a special education student, and whether he had

been classified as an English language learner. Recall that for each

charter school in the sample, the comparison group consists of the

three traditional public schools which were located nearest to it.

This ensures that all the schools in one group —consisting of one

charter school and its three nearest traditional public

schools—belong to the same neighborhood or community. As a check on

the robustness of the results, in one specification this brief

controls for neighborhood-specific factors to test whether the

results are biased by one type of schools being located in specific

communities. The results, however, remain very similar.

Since the dependent variable is a 0-1 dummy

variable, we run linear probability models as well as logistic

regressions. Since the findings are very similar, only the results

from the latter analysis are reported. Also, for ease of exposition,

the odds ratios are reported instead of the actual coefficients. The

odds ratio corresponding to a particular independent variable shows

the effect of that variable on the relative probability that the

outcome (dependent) variable will happen, controlling for other

factors. An odds ratio of less than 1 suggests that students with

that characteristic had a lower probability of leaving their

schools. Conversely, characteristics with an odds ratio greater than

1 imply that students with that characteristic had a higher

probability of leaving. For example, the fact that the odds ratio on

the charter dummy is 0.68 in column 1 in Table 10 means that

compared with a student in a nearby traditional public school, a

student in a charter school was only 68 percent as likely—or

equivalently, 32 percent less likely—to leave his or her

kindergarten school.

Regression Results. Students in charter

schools had a significantly smaller probability of leaving their

schools within three years of starting kindergarten, relative to

their peers in traditional public schools. Most of the demographic

factors are associated with mobility in expected ways, with black

students, students from low-income families, and special education

students leaving at higher rates.

Compared with her peer in a neighboring

traditional public school, a kindergartener in a charter school left

her original school at a rate that is about one-third lower (see

Table 10, column 1). When different background variables,

classification statuses, and rates of absenteeism are included the

difference gets narrowed—but still students in charter schools are

23 percent to 29 percent less likely than their peers in traditional

public schools to leave their schools. Note, however, that there may

be differences between students attending charters and those

attending nearby traditional public schools that this brief has not

been able to capture, and part of the gap in observed attrition

patterns across these schools might be due to those factors rather

than to attending a particular type of school. Note also

that because this brief is looking at mobility patterns of students

starting out as kindergarteners and following them over the next

three years, we do not have any data on academic performance of

these students that predate the mobility patterns which are

analyzed.15 Our analysis does not additionally control

for student achievement in the regression analysis.

|

Table 10:

Following Kindergarteners in 2008-2009 Through the Next

Three Years, Logistic Regressions, With Odds Ratios

Dependent variable: Whether left one’s original

(kindergarten, 2008-2009) school within three years

|

||||

|

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

|

Charter |

0.68*** |

0.60*** |

0.77*** |

0.71*** |

|

Female |

|

0.92** |

0.96 |

0.96 |

|

Lunch-eligible |

|

1.23*** |

1.14** |

1.10* |

|

White |

|

0.58*** |

0.59*** |

0.61*** |

|

Black |

|

1.03 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

|

Hispanic |

|

0.79** |

0.79** |

0.76** |

|

Asian |

|

0.61*** |

0.67*** |

0.71** |

|

English Language |

|

|

0.83*** |

0.84** |

|

Special Education Student |

|

|

1.61*** |

1.61*** |

|

Number of

Days Absent |

|

|

1.03*** |

1.03*** |

|

Observations |

10,251 |

10,251 |

10,251 |

10,251 |

|

Neighborhood

Fixed Effects |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

|

SOURCE: IBO analysis of Department of Education data

NOTE: One asterisk (*) denotes statistical significance at

the 10 percent level, two asterisks denote statistical

significance at the 5 percent level, and three asterisks

denote statistical significance at the 1 percent level.

Independent Budget

Office |

||||

Student Demographics and Mobility. Most of

the demographic factors are associated with mobility in expected

ways. Female students in the study cohort were no more likely than

their male counterparts to leave their schools. But students from

low-income backgrounds, proxied by eligibility for free or

reduced-price lunches, had higher rates of leaving. White students,

and to a lesser extent Asians and Hispanics, were less likely to

leave their schools than black students. The incidence of leaving

was strikingly high for special education students—they left at

close to twice the rate for general education students. In contrast,

ELL students changed schools at a significantly lower rate. As one

would expect, the number of days that a student was absent is a

significant predictor of subsequent attrition.

We also tested to see whether demographic

factors affected the mobility of students in charter schools

differently. For brevity, these results are not shown, but they are

along expected lines. One interesting result is that differences in

the rate at which low-income students and students at other income

levels leave their schools are much smaller in charter than in

traditional public schools: low-income students in charter schools

leave school at almost the same rate as

students at other income levels. We also find that

absenteeism is an even greater predictor of turnover for students in

charter schools, compared with its predictive power for students in

nearby traditional public schools and, not surprisingly, find that

special education students in charter schools leave at very high

rates.

What factors predict student transfer to another

New York City public school? Are these the same factors that are

associated with leaving the city’s public schools?

When students leave a New York City public school, they can either go to

another city public school, or they can leave the city’s public

schools altogether. Students in charter schools transferred to

another New York City public school at much lower rates compared

with students in nearby traditional public schools. However, the

differences are smaller for the probability of leaving the New York

City public school system. The effects of various demographic

variables and student classification statuses also vary according to

whether one is looking at the incidence of transferring to another

DOE school or whether one is studying attrition out of the city’s

public schools. This brief employs multinomial regression models to

analyze this question.

Students in charter schools transferred to another of the city’s

public schools at much lower rates—they were 40 percent less likely

to transfer out as compared with students in nearby traditional

public schools. However, they were only 19 percent less likely to

leave the system (see Table 11, columns 1 and 2).

|

Table 11: Following Kindergarteners in 2008-2009 Through the

Next Three Years, Multinomial Logit Regressions,

Baseline Status is “Remain in

same school”; Status = 2 is “Transfer to another NYC Public

School”; Status = 3 is “Left NYC Public Schools |

||||||||

|

|

Status=2 |

Status=3 |

Status=2 |

Status=3 |

Status=2 |

Status=3 |

Status=2 |

Status=3 |

|

Charter |

0.60*** |

0.81*** |

0.52*** |

0.74*** |

0.69*** |

0.91 |

0.61*** |

0.89 |

|

Female |

|

|

0.90** |

0.96 |

0.95 |

0.98 |

0.95 |

0.98 |

|

Lunch-eligible |

|

|

1.61*** |

0.84*** |

1.49*** |

0.78*** |

1.41*** |

0.79*** |

|

White |

|

|

0.61*** |

0.56*** |

0.61*** |

0.57*** |

0.66** |

0.56*** |

|

Black |

|

|

1.11 |

0.93 |

1.06 |

0.89 |

1.04 |

0.91 |

|

Hispanic |

|

|

0.82 |

0.75* |

0.83 |

0.74* |

0.79* |

0.73* |

|

Asian |

|

|

0.66** |

0.55*** |

0.74* |

0.59*** |

0.86 |

0.56*** |

|

English Languauge Learner Student |

|

|

|

|

0.81*** |

0.87 |

0.81*** |

0.9 |

|

Special Education |

|

|

|

|

1.86*** |

1.17 |

1.89*** |

1.16 |

|

Days Absent |

|

|

|

|

1.03*** |

1.02*** |

1.03*** |

1.02*** |

|

Observations |

10,251 |

10,251 |

10,251 |

10,251 |

||||

|

Neighborhood Fixed Effects |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

||||

|

SOURCE: IBO analysis of Department of Education data

NOTE: One asterisk (*) denotes statistical significance at

the 10 percent level, two asterisks denote statistical

significance at the 5 percent level, and three asterisks

denote statistical significance at the 1 percent level.

Independent Budget Office |

||||||||

Free

or reduced-price lunch eligible students have a significantly higher

likelihood of transferring to another New York City public school,

but are not more likely to leave the city’s public schools. The

overall higher mobility of students from low-income families stems

from transferring to other New York City public schools; these

students are actually significantly less likely to leave the system

compared with students from middle- and upper-income families.

Similarly, special education students are more likely to transfer

within New York City’s public school system than to leave the

system. An ELL student has a lower probability of transferring out

as well as of quitting the system, although the effects are

statistically significant only in the former case.

The one variable which has consistent power for predicting attrition

is the number of days a student had been absent.

Conclusion

The results—consistent across both simple

cross-tabulations and a more sophisticated regression analysis—can

be summarized as follows. First, on average, students in charter

schools leave their schools at a lower rate than students at nearby

traditional public schools.

Second, this is the case even when this brief disaggregates the overall student population into various subgroups, based on gender, race, poverty status, and English language learner status. For most subgroups, students in charter schools leave their schools at a lower rate.

Third,

the big exception is special education students, who leave charter

schools at a much higher rate than either general education students

in charters or special education students in traditional public

schools. Charter schools enroll a disproportionately lower share of

students classified in special education compared with nearby

traditional public schools, although among charter school students

there is a big jump in classification rates in first grade.

Fourth, among students in both charter schools

and nearby traditional public schools, those who remained in their

kindergarten schools through third grade had higher test scores and

proficiency ratings in third grade for both reading and mathematics.

However, the achievement gap between stayers and movers was

considerably larger in charters compared with traditional public

schools and was much larger for mathematics than for reading.

Finally, looking at the third grade performance of students who started kindergarten in traditional public schools but later switched to charter schools, they had lower test scores compared with the stayers in charter schools, but higher test scores than those who transferred out from charter schools.

These results are likely caused by many factors. While there may be

causal effects of attending charter schools, it is possible that

other factors such as unobserved differences in student

characteristics contribute to some of the gaps in mobility patterns.

Also, charter schools in New York City are still in the process of

evolving and maturing. With the recent opening of many new schools

during the Bloomberg Administration, traditional public schools have

also seen considerable change in recent years. How these changes

play out will affect student migration patterns in the future.

This report prepared by Joydeep Roy

Endnotes

1See, for example, Hanushek, Kain, and Rivkin, “Disruption versus

Tiebout Improvement: The Costs and Benefits of Switching Schools,”

Journal of Public Economics, Volume 88/9-10, 2004; and Roy, Maynard,

and Weiss, “The Hidden Costs of the Housing Crisis: The Long-term

Impact of Housing Affordability and Quality on Young Children’s Odds

of Success,” written for the Partnership for America’s Economic

Success, 2008,

www.pewtrusts.org/our_work_report_detail.aspx?id=47132

2Bifulco and Ladd, “The Impact of Charter Schools on Student

Achievement: Evidence from North Carolina,” Education Finance and

Polcy, 1(1), Winter 2006; and

Hanushek, Kain, Rivkin, and Branch, “Charter School Quality

and Parental Decision-Making with School Choice,” Journal of Public

Economics, Volume 91 (5-6) June 2007; find charter shcool students

to have a higher rate of attirion than their counterparts in

traditional public schools, but a study of middle school students

did not find any significant difference (see Nichols-Barrar, Tuttle,

Gill, and Gleason, Student Selection, Attrition, and Replacement in

KIPP Middle Schools, Mathematica Policy Research, 2011).

3This is particularly likely to be the case for elementary school

students, as literature documents that families of such students are

unwilling to have them travel long distances from home for school.

Note, however, that some of New York City’s students also attend

parochial schools and—to a lesser extent—independent private

schools, and some charter schools also draw their students from

these schools.

4New York’s charter law requires charter schools in New York City to

give preference to students who reside in the local Community School

District in which the charter school is located, see New York State

Education Law § 2854 2. (b).

5The traditional public schools that belong to a charter school’s

comparison group are generally unique. However, 21 traditional

public schools belong to the comparison group for two separate

charter schools, and 6 traditional public schools each belong to the

comparison groups for three charter schools.

6The second half of the 2000s was a period of rapid growth of

charter schools in New York City. For example, 18 charter schools

started operating during 2007-2008, and more expanded their grade

spans. By contrast, there were only 17 charter schools overall

operating in New York City when Mayor Michael Bloomberg took office

in 2002 (see Winters,“Measuring the Effect of Charter Schools on

Public School Student Achievement in an Urban Environment: Evidence

from New York City,” Economics of Education Review, Volume 31, Issue

2, April 2012).

7For the small number of schools with missing x and y coordinates

the NYCgbat program was used to transform the street address into x

and y coordinates.

8Note that this difference in racial composition is unlikely to stem

from differences in composition of the respective neighborhoods, as

this brief only compares charter schools with their three

geographically closest traditional public schools.

9Though students who do not return valid forms

regarding their family’s income level are classified as “full price”

by the New York City DOE, our data allow us to identify those

students who actually submitted a valid form indicating their

ineligibility for the free/reduced-price lunch program and it is

these data that this brief uses. Note that full price

means that the family has reported income above the 185

percent of poverty level threshold for meal subsidy.

10See the reports by the New York City Charter School Center (2013)

and Winter’s (2013) for the Center on Reinventing Public Education.

11We restrict our attention to the 2,656 students still continuing in

the city’s public schools after three years, rather than the full

population of 3,043 students, since there are no data on special

education status for those 387 students who had left New York City

public schools.

12See the reports by the New York City Charter School Center

(Students with Special Learning Needs and NYC Charter Schools,

2012-2013,

www.nyccharterschools.org/sites/default/files/resources/SpecialNeedsFactSheetApril2013.pdf) and Winters for the Center on Reinventing Public Education

(Special Education and New York City Charter Schools,

www.crpe.org/publications/why-gap-special-education-and-new-york-charter-schools).

13The share of special education students is very high among those

repeating a grade.

14The measures of student achievement that this brief uses come from

the results of standardized tests administered by New York State—it

focuses on test results from grade 3 in 2011-2012. Student

performance on the test is translated into an overall scale

score—scale scores ranged from 644 to 780 for English Language Arts

and 662 to 770 for mathematics in 2011-2012 (see

https://reportcards.nysed.gov/statewide/2012statewideRC.pdf). Performance is also assessed in terms of performance level

descriptors as follows. For more details see The New York State

Report Card for NYC Chancellor’s Office (2011-2012), available at

https://reportcards.nysed.gov/files/2011-12/RC-2012-300000010000.pdf:

English

Language Arts

Level 1:

Below Standard

Student

performance does not demonstrate an understanding of the English

language arts knowledge and skills expected at this grade level.

Level 2:

Meets Basic Standard

Student

performance demonstrates a partial understanding of the English

language arts knowledge and skills expected at this grade level.

Level 3:

Meets Proficiency Standard

Student

performance demonstrates an understanding of the English language

arts knowledge and skills expected at this grade level.

Level 4:

Exceeds Proficiency Standard

Student

performance demonstrates a thorough understanding of the English

language arts knowledge and skills expected at this grade level.

Mathematics

Level 1:

Below Standard

Student

performance does not demonstrate an understanding of the mathematics

content expected at this grade level.

Level 2:

Meets Basic Standard

Student

performance demonstrates a partial understanding of the mathematics

content expected at this grade level.

Level 3:

Meets Proficiency Standard

Student

performance demonstrates an understanding of the mathematics content

expected at this grade level.

Level 4:

Exceeds Proficiency Standard

Student

performance demonstrates a thorough understanding of the mathematics

content expected at this grade level.

15The first time these students are observed taking the New York

State tests is when they are in grade 3 in 2011-2012 (spring 2012).

PDF version available here.

Receive notification of free reports by e-mail