Introduction

Over the past several months the

Department of City Planning has outlined its proposed East

Midtown rezoning initiative in a series of public reports

and presentations. The new zoning regulations would

encourage the redevelopment of the neighborhood’s existing

building stock by allowing developers to build taller and

denser than currently permitted. The proposal officially

began the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) process

on April 22 of this year, which includes reviews by the

local community boards, the Manhattan Borough President, the

City Planning Commission and, ultimately, the City Council.

The city planning department and

the supporters of the rezoning proposal have argued that the

office buildings in East Midtown, and particularly the

blocks surrounding Grand Central, are outdated, inefficient

and ill-suited to the needs of modern office tenants. This

is due, in part, to current zoning regulations that

discourage landlords in East Midtown from replacing their

inefficient buildings with modern structures. Many buildings

in the area, particularly those built before 1961, are

larger than could be built under the current zoning code.

As a result, the Grand Central

submarket has seen little new development over the last

several decades, and the amount of new office stock added to

the area has fallen well short of what was built before the

current zoning rules were put in place in the early 1980s.

Supporters of rezoning argue that unless the zoning code is

revised, East Midtown—and, by extension, New York City—will

be less competitive on the global stage as compared with

peer cities like Chicago, London, and Tokyo.

The proposal includes several

provisions intended to benefit the area’s existing workers,

residents, and visitors. The new zoning text includes

provisions in which developers could purchase additional

density from a District Improvement Fund in order to reach

the maximum development potential of their sites. The money

raised by the fund would be used to pay for capital

improvements to the area’s pedestrian and transportation

infrastructure. New buildings would also be required to meet

a higher energy efficiency standard than required at sites

elsewhere in the city.

Based on estimates in the final

scope for the project’s Environmental Impact Statement, the

rezoning could lead to 13.5 million square feet of new

development throughout East Midtown, including between 8.2

million square feet and 10.3 million square feet of office

space, of which as much as 3.7 million would be net new

space.

Some elected officials and

advocates, however, are concerned the rezoning is proceeding

too quickly and that more time is needed to understand the

impact these new buildings will have on the public realm.

Given that crowded conditions already exist in the area,

they contend that the capital improvements to the area’s

pedestrian and transit network should precede development of

new commercial space and question whether payments by

developers into a District Improvement Fund will be too

volatile a funding source for the needed improvements. Some

are concerned that the rezoning will target historic

buildings for redevelopment. Still others have questioned

whether the rezoning will draw tenants and development

interest away from other active redevelopment areas,

including the World Trade Center, Downtown Brooklyn, and

Hudson Yards, where the

city is spending $3 billion to spur the creation of a new

central business district with more than 25 million square

feet of office space. In response to this last concern,

developers will not be able to receive building permits for

projects approved under the new zoning rules until July

2017.

In this report, requested by

Council Member Daniel Garodnick, IBO updates its 2004

report, "

Supply

& Demand: City and State May Be Planning Too Much Office

Space," to look at the

future of the office market in New York City. That report

forecast employment growth among office-using industries

from 2010 through 2035, translated those gains into demand

for new office space, and compared that estimate with the

amount of potential office development capacity proposed in

several rezonings that were pending at that time. In this

update, IBO projects citywide growth through 2040 and

compares the forecast demand with an updated estimate of

development capacity that includes Hudson Yards, the World

Trade Center, Long Island City, Downtown Brooklyn, Atlantic

Yards, and the proposed East Midtown rezoning.1

|

East

Midtown District Improvement Fund

The zoning proposal acknowledges that

increasing density in the area will add to already

overburdened transportation and pedestrian networks.

Foregoing the option to use the city’s general capital

budget to finance improvements to help mitigate the

pressure, the proposed rezoning of East Midtown includes a

financing mechanism known as the District Improvement Fund

(DIF) to raise revenue from the sale of additional

development rights. The fund is similar to the one that the

city employed when it rezoned the Far West Side of

Manhattan. Under the current proposal, developers can choose

to pay a bonus for each incremental square foot of space

they build over what is allowed as-of-right, up to a maximum

amount of space that varies based on a lot’s location. After

acquiring a minimum amount of floor area from the DIF,

developers can also add density by purchasing unused

development rights from neighborhood landmarks, including

Grand Central Terminal and St. Patrick’s Cathedral, instead

of buying air rights from the DIF.

The city has

proposed a price of $250 for each square foot of commercial

development rights acquired through the District Improvement

Fund. (The price for residential space will be determined at

a future date.) The price will be adjusted annually based on

the percent change in the Mayor’s Office of Management and

Budget’s estimate of the average asking rent for office

space in Midtown Manhattan. (Since developers cannot secure

building permits based on the new zoning regulations until

2017, it is unclear whether the DIF price will rise between

the rezoning’s enactment date and 2017, when developers will

be eligible to receive building permits, or whether it will

start at $250 at that time.)

Based on this pricing structure,

the city estimates that the DIF will raise between $605

million and $750 million over 20 years (present value). Even

though the city planning department estimates that there are

only 19 probable development sites that will take advantage

of the rezoning, the department has not provided a

site-by-site breakdown of expected DIF revenue. It has

estimated that the range of contributions could vary from

$30 million to $100 million per site. It also has not

estimated the timing or pace at which it expects to collect

DIF revenue or the extent to which allowing owners of

landmarks to sell unused development rights might divert

revenue from the District Improvement Fund.

The city’s proposal calls for the

creation of a District Improvement Fund Committee, which

will be tasked with deciding how and where DIF revenue is

spent. In the most recent version of the East Midtown zoning

amendment, the DIF Committee will identify capital projects

in or adjacent to East Midtown that are intended to improve

the neighborhood’s pedestrian networks; build new open

space; or mitigate the impacts of new development projects.

The committee will include five members, all of whom will be

appointed by the Mayor, and will be headed by the Chair of

the City Planning Commission. The committee would include

fewer points of view than the boards of other quasi-public

local development corporations. The board of the Hudson

Yards Development Corporation, for example, includes eight

mayoral appointees, plus the Comptroller, the Speaker of the

City Council, the Council Member representing the

neighborhood, the Manhattan Borough President, and the Chair

of Community Board 4. As IBO

completed this rpeort, the city’s planning department

indicated that it was open to considering changes in the

composition of the DIF Committee and the per square foot

price of development rights purchased through the fund.

The Final Scope of Work for the

project’s Environmental Impact Statement recommends that the

committee prioritize the renovation of subway platforms and

mezzanines in Grand Central station and the conversion of

Vanderbilt Avenue into a pedestrian plaza. Depending on the

availability of funding, future projects could include

streetscape and sidewalk improvements along Madison Avenue,

Lexington Avenue, and East 53rd Street, as well

as improvements to the 5th Avenue/53rd

Street and Lexington Avenue/53rd Street subway

stations. The city planning and transportation departments

recently hired a consultant to write an "East Midtown Public

Realm Vision Plan," which the agencies expect will propose

specific capital projects in greater detail. At the time of

this report, city planning has not publicly released the

estimated cost of these projects. The ultimate decision of

which projects to fund and the order in which they will be

funded would be left to the discretion of the DIF Committee.

Many of these projects would

address concerns about congestion in Midtown that date back

to at least the 1970s. The "Midtown Development" report,

released by the Department of City Planning in 1981 in

support of the proposal to create the Special Midtown

District, highlighted the need for significant investments

to ease overcrowding in East Midtown. Among the proposed

projects were recommendations to widen the Madison and

Lexington Avenues sidewalks to at least 17 feet; improve

pedestrian circulation along East 53rd Street and

Vanderbilt Avenue; and relieve congestion above and below

ground at Grand Central. The projects included in the city’s

current DIF proposal tackle these same issues, which have

largely gone unaddressed in the three decades since the

Special Midtown District was approved. The special district,

which was enacted in 1982, first established the zoning

restrictions in East Midtown that the Mayor is currently

proposing to revise.2

In a recent opinion article, Mayor Bloomberg suggested

that the city might pay for at least some of the East

Midtown capital improvements using city capital funds and

use future DIF revenue to reimburse the city over time. Such

an agreement between the city and the DIF Committee would

most likely be structured similarly to the arrangement

between the city and the Hudson Yards Development

Corporation and the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation.

Experience with the Hudson Yards equivalent of the DIF

(known as a DIB, or district improvement fund bonus),

however, has shown that such funding is that project’s most

volatile source of revenue. Annual DIB revenue in Hudson

Yards has ranged from as much as $58 million in fiscal year

2007 to as little as $0 in fiscal year 2010. The city has

not said whether all of the envisioned capital projects will

proceed if DIF revenue falls short of the total of the

projected costs.

|

Forecasting Demand for

Office Space

As discussed in IBO’s 2004 report,

forecasting long-term demand for office space is highly

sensitive to both projected employment growth and to how

intensively firms use office space. Those factors are, in

turn, a product of the broader economy, changes in the

city’s local economic conditions, tax incentives, inter- and

intra-regional competition, technological innovations,

changes in workplace design, as well as other developments

that we cannot yet envision. Making assumptions about

employment and the use of office space, IBO estimates that

roughly 52 million square feet of office space would need to

be developed to meet projected citywide employment growth

through 2040. However, this long-term forecast of demand

comes with a large margin of error. Depending on the rate of

employment growth and space utilization trends, by 2040

demand for new space could be as little as 30 million square

feet or as much as 87 million square feet.

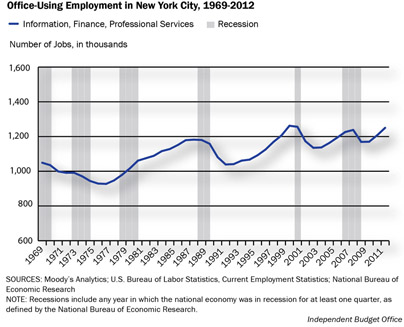

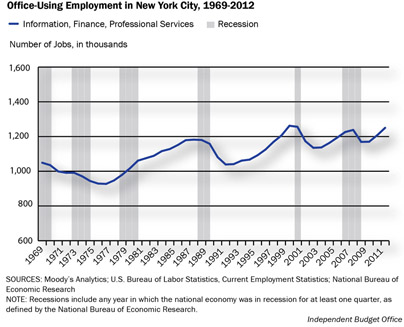

Employment Forecast.

Historical trends in employment in the office-using

industries are used to generate an employment forecast

through 2040. IBO’s definition of office-using employment

includes the three sectors that represent the largest share

of demand for office space in the city: information,

financial services, and professional and business services.3

Estimates of annual employment by industry from 1970 on are

provided by Moody’s Analytics. IBO added its own employment

estimate for 1969, a cyclical peak, which was not available

from Moody’s. To estimate office-using employment, we looked

at trends in total employment in New York City and

employment in the city’s finance, insurance, and real estate

industry. Both of these series peaked in 1969, declining

1.37 percent and 1.34 percent, respectively, from 1969 to

1970. IBO assumes a comparable, 1.35 percent, decline in

office-using employment for the year.

To get a

sense of how the demand for office space has grown over

time, we calculated the long-term, peak-to-peak employment

growth rates for the combined information, financial

services, and professional and business services industries

in New York City since 1969. Average annual growth rates are

highly dependent on the beginning and end years selected,

and peak-to-peak trends best capture the need for new office

development as the city’s employment base grows across

multiple business cycles. By using peak-to-peak employment

growth rates to model growth in office-using industries, we

are assuming that employment growth during recoveries will

eventually be offset—at least in part—by job losses during

recessions. The office-using industries’ peak-to-peak

employment growth rates have fallen over the past three

business cycles, slowing from increases averaging 0.63

percent annually from 1969 through 1988 to declines

averaging 0.24 percent a year during the most recent cycle.

|

Growth in Office-Using

Employment Slowed Over Time

|

|

Peak-to-Peak

Economic Cycles

|

Average Annual

Growth Rate

|

|

1969-1988

|

0.63%

|

|

1988-2000

|

0.55%

|

|

2000-2008

|

-0.24%

|

|

1969-2008

|

0.43%

|

|

SOURCES: Moody’s

Analytics; Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current

Employment Statistics

NOTES: Employment

totals are estimated by Moody’s Analytics to bridge

between multiple industrial classification systems

and data sources. Employment for 1969 was estimated

by IBO based on data from the US Bureau of Labor

Statistics’ Current Employment Statistics data.

Independent

Budget Office

|

Overall, citywide office-using

employment is roughly at the same level it was more than a

decade ago. As of the end of 2012, there were nearly 1.25

million workers employed in the three office-using

industries. Collectively, the three sectors that make up

IBO’s definition of office-using employment have recovered

all of the jobs lost since 2008, though they have yet to

surpass their previous peak in 2000. There are a number of

possible explanations for this continued weakness,

including: the increasing use of technology; the

near-shoring, off-shoring, and/or elimination of back-office

occupations; and structural shifts in office-using

industries in the city, particularly in the financial

services sector.

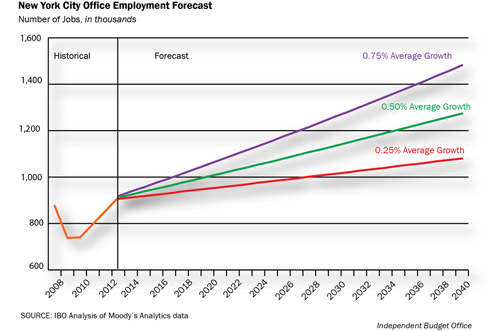

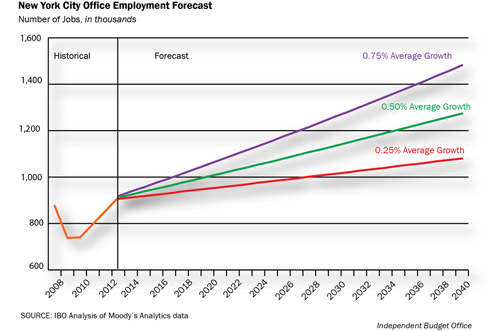

Based on these historical trends,

IBO projected office-using employment in New York City

through 2040. We modeled three scenarios based on different

annual growth rates derived from our analysis of long-term,

peak-to-peak employment growth:

•

0.75 percent (an optimistic scenario that reflects

the city’s strong job growth since the end of the

2009 recession);

•

0.5 percent (roughly the long-term growth rate

between 1969 and 2008); and

•

0.25 percent (a pessimistic scenario).

These various growth rates were

then applied to the 2012 office-using employment base. Using

2012 as the base year underestimates future employment

because we are applying our long-term growth rates to a

point in time in the middle of an economic expansion, rather

than at the cycle’s peak. This is preferable to starting our

forecast from the 2008 peak, which would have omitted data

on employment trends from 2008 through 2012. Moreover, 2012

office-using employment has surpassed its 2008 peak.

Based on these assumptions, New

York City would add between 91,000 new jobs in the more

pessimistic case and 291,000 office jobs in the more

optimistic scenario. The midrange scenario of 0.5 percent

annual growth, which is closest to the long-term annual

growth rate since 1969, would result in 187,000 new office

jobs by 2040. The uncertainty in the forecast increases over

time. Through 2020, the difference between the optimistic

and pessimistic scenarios is 52,000 jobs. By 2040, the

difference grows to more than 200,000 jobs.

Demand Forecast.

These employment growth scenarios can

be used to estimate the demand for new office space. Over

time, employment growth will reduce the overall vacancy rate

enough to justify the construction of new buildings. By

multiplying the total employment increase by an estimate of

the amount of space required per worker, we can estimate the

total amount of new development needed to accommodate this

projected growth.

Like

employment growth rates, space utilization rates have varied

over time. Traditionally, office designers have estimated

that workers require 250 square feet of space per person.

The amount of office space needed for each worker, however,

has steadily fallen in recent years for a variety of

reasons, including the decreasing need for file storage and

server space, the increasing popularity of open floor plans,

a renewed focus on controlling costs as firms in New York

compete in a worldwide market for financial and business

services, and the rise of telecommuting and shared

workspaces. Several commercial real estate experts have

predicted that firms could allocate as little as 100 square

feet per worker by the end of the decade.4

To account for the range of

potential firm decisions, IBO applied four utilization rates

to each of the employment growth scenarios discussed above.

The utilization rates vary from a high of 250 square feet

per worker to a low of 175 square feet per worker; the

latter figure is roughly in line with what firms currently

allocate per worker when leasing space.

The model also allows the overall

market to return to a natural vacancy rate of 8 percent, the

point at which supply and demand are balanced and lease

rates are stable. According to Cushman & Wakefield’s final

2012 market report, the vacancy rate in Manhattan was 9.4

percent, meaning that the market would need to absorb 5.5

million square feet of space before new construction would

be considered viable. We have chosen to focus on vacancy

rates in Manhattan’s central business districts since there

appears to be little demand for new office construction in

other areas of the city.

Other Factors Affecting Long-Term

Demand. Other factors that might affect the long-term

demand include conversion or demolition of existing office

buildings and changes in how office space is used. It is

difficult to estimate the total amount of office space that

has been converted to other uses in recent years. It is

likely that most conversion activity over the past two

decades resulted from the now-expired 421-g incentive

program, which encouraged property owners to convert office

buildings in Lower Manhattan into apartments. From 1995

through 2006, the years in which the exemption was

available, developers converted nearly 12.8 million square

feet of offices into residential buildings.

Conversion activity has slowed in

the years since then, but it appears that developers are

continuing to convert older office buildings even in the

absence of a dedicated tax incentive. Notable projects

include apartment conversions at 116 John Street and 114

East 32nd Street in Manhattan and 25 Washington

Street in Brooklyn; a retail conversion at 3 West 57th

Street; and hotel conversions at 140 Washington Street, 960

6th Avenue, and 1164 Broadway. Based on media

reports, current and future conversion projects include

Sony’s headquarters at 550 Madison Avenue, 346 Broadway, the

former Emigrant Savings Bank at 49-51 Chambers Street, the

upper floors of the Woolworth Building, and AIG’s former

headquarters at 70 Pine Street.

For the purposes of this analysis,

IBO has assumed that by 2040, owners of office properties in

Manhattan’s central business districts and in Downtown

Brooklyn, neighborhoods that feature both strong residential

demand and a preponderance of the city’s oldest office

buildings, will convert or demolish 10 percent of those

neighborhoods’ prewar office space and 5 percent of its

space built from 1946 through 1961. This amounts to a total

of 19.9 million square feet in conversions and demolitions,

or an average of 738,000 square feet per year. If employment

growth remains steady, the market would need to replace the

space that is lost.

Some of the demand created by

conversions and demolitions might be offset if businesses

decide to shrink their office footprints over time. If the

city’s existing office-using industries, as defined in this

report, were to collectively reduce their space utilization

rates by as little as 6 percent—the equivalent of going from

250 square feet per worker to 234 square feet per worker—the

additional vacant space would more than offset all of the

extra demand generated by conversions and demolitions. Given

the speculative nature of how and when businesses might

reconfigure their existing office space, our model does not

consider potential reductions in the amount of space

currently occupied by the existing office workforce.

|

Office Employment and Space Requirements Through 2040

|

|

|

Average Annual Growth Rate

|

|

|

0.75%

|

0.50%

|

0.25%

|

|

Office

Employment

(thousands of jobs)

|

|

|

|

|

Level in 2040

|

1,540.5

|

1,437.0

|

1,340.2

|

|

Gain from 2012-2040

|

290.8

|

187.3

|

90.5

|

|

Space

Required Assuming 8% Vacancy Rate, 19.9 msf in

Conversions

(millions of square feet)

|

|

|

|

|

250 square feet per job

|

87.1

|

61.3

|

37.1

|

|

225 square feet per job

|

79.9

|

56.6

|

34.8

|

|

200 square feet per job

|

72.6

|

51.9

|

32.5

|

|

175 square feet per job

|

65.3

|

47.2

|

30.3

|

|

SOURCE: Moody’s Analytics

Independent Budget Office

|

In the midrange estimate, in which

employment grows at roughly the historical average growth

rate of 0.5 percent each year and companies provide an

average of 200 square feet per worker, we estimate that

there will be demand for 52 million square feet of space, a

figure which includes the need to replace 20 million square

feet of space lost to conversions and demolitions. However,

the range of scenarios puts the demand for office space

through 2040 resulting from office-using employment growth

as high as 87 million square feet or as low as 30 million

square feet.

The considerable uncertainty in

these results shows how sensitive the long-term demand for

office space is to small changes in assumptions about the

employment growth rate or the amount of space that

businesses allocate per worker. If space utilization rates

and conversion activity are held constant, reducing the

average annual growth rate from 0.75 percent growth to 0.5

percent growth would cut the total demand for office space

by about 30 percent. If office employment only rises by an

average of 0.25 percent, demand would fall by as much as 57

percent as compared with the 0.75 percent growth scenario.

Similar reductions would occur if

companies decide to allocate less space per worker. Holding

employment growth and conversions constant, every 25 square

foot reduction in the space needed per worker decreases the

total demand for net new office space by 6 percent to 10

percent.

The 2011 Cushman & Wakefield study

projected that the city would need an additional 92 million

square feet of office space by 2040. While that amount is

similar to IBO’s most optimistic scenario, it is nearly 80

percent higher than our midrange estimate. That demand

estimate could prove to be overly optimistic should

employment growth prove sluggish or if employers continue to

shrink the amount of space they allocate per worker.

|

Cushman & Wakefield Office

Forecast Methodology

|

|

The real estate firm of Cushman &

Wakefield published long-term forecasts of Manhattan’s

office, hotel, residential, and retail markets as part of

the city’s due diligence for the 2006 and 2012 Hudson Yards

bond offerings. The city justified the need for the rezoning

of the Far West Side in part based on the gap that the firm

found between future demand for office space and available

supply under existing zoning regulations.

In its 2012 report, Cushman &

Wakefield estimated that office-using employment growth

would generate demand for 91.9 million square feet of office

space in Manhattan through 2041, including 48.6 million

square feet in Midtown, 25.3 million square feet in Hudson

Yards and 18 million square feet Downtown. This dramatically

exceeded the 43 million square feet of office space that

could be accommodated by Manhattan’s existing development

sites, based on then-current zoning regulations. According

to this market analysis, the rezoning of Hudson Yards would

capture a significant share of this potentially unmet demand

without negatively affecting Manhattan’s other commercial

districts.

Cushman & Wakefield arrived at its demand estimate based

on a regional forecast of the office-using employment

developed by Moody’s Analytics. The report notes that, after

taking into account job gains and losses over multiple

recessions, office-using employment in the region would grow

at an average annual rate 0.7 percent, while employment in

the city would grow at an average annual rate of 0.77

percent through 2041. Cushman & Wakefield then translated

employment growth into the regional demand for office space,

which was divided among the six regional submarkets, using a

series of regression models based on the historical

relationship between employment growth and the net

absorption of office space dating back to 1986. Their model

considers other factors as well, including the destruction

of the World Trade Center in 2001 and year-to-year changes

in the availability of incentives offered by different local

governments, the cost of capital, and each market’s share of

occupied office space in the region.

|

Forecasting Supply of New Office Development

Given our forecast of demand for

new office space, we now turn our attention to projecting

the future supply of office buildings that will be available

to meet that demand. IBO considers new buildings currently

under construction, office conversion projects and publicly

known development sites located throughout the city, as well

as new capacity that could be added in East Midtown. IBO

projects that current development capacity is about 44

million square feet, increasing to 48 million if the East

Midtown rezoning is approved.

|

New Office Construction Primarily in World Trade Center and

Hudson Yards

In

millions of square feet

|

|

Property

|

Total Size

|

Available Space

|

|

1 World Trade Center

|

3.0

|

1.3

|

|

4 World Trade Center

|

2.3

|

1.1

|

|

Hudson Yards South Tower

|

1.7

|

0.5

|

|

250 West 55th St

|

0.9

|

0.4

|

|

7 Bryant Park

|

0.4

|

0.4

|

|

51 Astor Place

|

0.3

|

0.3

|

|

330 Hudson Street

|

0.3

|

0.3

|

|

1000 Dean Street

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

|

TOTAL

|

9.0

|

4.4

|

|

NOTE: Only includes projects of at least 100,000 square feet.

Independent Budget Office

|

Projects in Construction.

There is 4.4 million square feet of

office space available to lease in buildings currently under

construction. The majority of this space is located in the 1

and 4 World Trade Center buildings, which, when completed,

will add to the Downtown market more than 5 million square

feet, of which 2.9 million square feet has already been

leased. The next largest building is a 1.7 million square

foot tower—three-quarters of which has been leased or sold

to tenants—that the Related Companies is currently building

in Hudson Yards. The remaining buildings are boutique office

buildings of less than a million square feet, most of which

are less than 500,000 square feet. One current conversion

project, located at 1000 Dean Street in the Crown Heights

neighborhood of Brooklyn, is transforming a former auto

garage and warehouse into shared office space. Though we

have only identified projects of at least 100,000 square

feet, there are also a number of small office projects under

construction in the Soho, Meatpacking, and Far West Chelsea

neighborhoods.

Development

Sites.

There are also a number of potential

development sites throughout the city that could accommodate

office projects in the future.

In the 2012

Hudson Yards bond offering, Cushman & Wakefield identified

19 locations outside of Hudson Yards that, based on

then-current zoning regulations, could potentially

accommodate new office buildings.7 IBO reviewed

the current status of these sites. Since the report was

published, three of the largest sites—the Hotel

Pennsylvania, 701 7th Avenue, and 221-225 West

57th Street—saw their developers opt to build (or preserve)

hotel, retail, or residential space rather than office

space. A fourth, the Port Authority Bus Terminal, stalled

after the authority failed to reach an agreement with its

development partner to build a tower over the bus station.

Five of the sites are under construction and were included

in our list of construction sites. The remaining sites

identified by Cushman & Wakefield are in our list of

potential development sites, including the stalled project

at the bus terminal.

Five other sites have been

proposed since the time of the Cushman & Wakefield report:

the sites assembled by SL Green at the corner of East 42nd

Street and Madison Avenue; 425 Park Avenue; a lumberyard on

9th Avenue and West 15th Street; the conversion of the

Domino Sugar Factory in Williamsburg, Brooklyn; and the

conversion of the Watchtower properties in DUMBO. Under

current zoning, the owners of the two East Midtown sites can

rebuild only the amount of office space currently located on

those properties. Since neither would add net new square

footage, we have excluded them from this analysis.

|

Far West Side Home to Most of Manhattan’s

Remaining Development Sites

In millions of square feet

|

|

Site

|

Net New Space

|

|

Announced Hudson Yards Sites

|

12.3

|

|

Potential Hudson Yards Sites

|

11.3

|

|

3 World Trade Center

|

2.8

|

|

2 World Trade Center

|

2.3

|

|

20 Times Square (Port Authority Bus Terminal)

|

1.5

|

|

45 East 45th Street (Roosevelt Hotel)

|

1.2

|

|

Watchtower Properties (Multiple Sites, Brooklyn)

|

1.2

|

|

304-322 Hudson Street (4 Hudson Square)

|

0.8

|

|

708 1st Avenue (Solow Site)

|

0.9

|

|

740 8th Avenue

|

0.9

|

|

292-314 Kent Avenue

(Domino Sugar

Refinery, Brooklyn)

|

0.6

|

|

341-347 Madison Avenue (MTA Headquarters)

|

0.3

|

|

75 9th Avenue (Chelsea Market)

|

0.3

|

|

61 9th Avenue (Prince Lumber)

|

0.2

|

|

TOTAL

|

36.6

|

|

SOURCE: Cushman & Wakefield

NOTE: For development sites in the proposed East

Midtown rezoning area, net new development potential

reported here is the difference between maximum

density allowed under current zoning and the

existing gross square footage on those sites.

Properties listed include only projects of at least

100,000 square feet of net new office space.

Independent Budget

Office

|

Approximately two-thirds of the

total potential office capacity is located in the Hudson

Yards district. Developers active in the Far West Side are

currently seeking tenants and financing for several towers

totaling 12.3 million square feet, while an additional 11.3

million square feet of development rights exist elsewhere in

the area. The Related Companies has reportedly reached an

agreement with Time Warner to occupy at least a portion of

its North Tower in the Hudson Yards project.

Outside Hudson Yards, there are

approximately 11.2 million square feet of potential net new

office development rights in Manhattan. Two of these

sites—the Roosevelt Hotel and the Metropolitan

Transportation Authority’s headquarters—are in the East

Midtown area proposed for rezoning; together they can

accommodate 1.5 million square feet of new office space

under current zoning regulations. Silverstein Properties is

seeking tenants for about 5 million square feet of space at

the 2 and 3 World Trade Center buildings. The firm is

currently building the foundations and street-level podiums

at both sites. Its financial backers, including the city and

state, have required Silverstein to reach specific office

leasing milestones before it can begin building the office

towers on each site. According to recent reports,

Silverstein has signed a letter of intent with a tenant to

lease a portion of 3 World Trade Center.8

Two portfolios in Brooklyn—the

Domino Sugar Refinery in Williamsburg and the Jehovah’s

Witnesses’ Watchtower properties in DUMBO—were recently sold

to developers that intend to convert at least some of the

properties from industrial uses to office space. Together,

the two projects could add as much as 1.8 million square

feet of new office space.

Additional

Capacity in Brooklyn and Queens.

The rezonings of Downtown Brooklyn,

Atlantic Yards, Long Island City, and Jamaica collectively

included the potential for nearly 12 million square feet of

office space. These rezoning initiatives reflect the efforts

of multiple mayoral administrations to expand the city’s

central business district into the other boroughs.

In the years since the plans were

approved, residential properties have accounted for nearly

all new development in those areas, though there remains

additional capacity should a market develop for modern

office space in the other boroughs. Since 2006, developers

have built three new build-to-suit office buildings totaling

1.4 million square feet in Long Island City, though no new

projects are proceeding there at the moment.

Since a detailed site-by-site

review of these areas was beyond the scope of this paper,

IBO instead assumed that one-quarter of the nearly 12

million square feet of development rights created in the

rezonings are still unused, which would translate into as

much as 2.9 million square feet of office space that could

be built in Brooklyn and Queens.

Citywide Capacity. Including

the 4.4 million square feet of office space that is still

available in sites currently under construction and the

potential for an additional 2.9 million square feet in

Brooklyn and Queens, the total amount of new development

capacity at known sites under existing zoning regulations is

nearly 44 million square feet.

Not all of these sites will

ultimately be developed as office buildings. The fact that a

site is zoned for office development does not guarantee that

its owner will ultimately build new office space,

particularly if there is little demand in that location or

if there is a "higher and better use" for the land. As

noted, the owners of several sites in Downtown Brooklyn and

Midtown West have opted to build residential or hotel

projects instead of office buildings in locations where the

zoning rules allowed either use.

East Midtown Rezoning.

The proposed rezoning of East Midtown

would come on top of the nearly 44 million square feet that

is either currently under construction or could be built in

other areas of the city.

The

Department of City Planning estimates that East Midtown

rezoning would allow from 8.2 million square feet up to 10.3

million square feet of office development over 20 years, of

which as much as 3.7 million square feet would be net new

space. If the East Midtown rezoning is approved, the

development capacity citywide would rise to 47.5 million

square feet of office space.9

In the aggregate, the rezoning

would need to capture only a small share of the citywide

demand for office space to be successful. The plan’s

proposed 3.7 million square feet of net new office space

represents only 10 percent of demand in IBO’s midrange

forecast through 2033 and 7 percent through 2040.

The rezoning’s small share of

overall demand does not, however, mean that development in

East Midtown will happen before or at the expense of

projects in Hudson Yards and the World Trade Center. The

city’s various office submarkets offer tenants different

amenities, floor plates, levels of transit accessibility and

price points. The proposed East Midtown projects might

appeal to a different set of tenants than would be willing

to move to the Far West Side or Downtown, and vice versa.

Properties in the Hudson Yards financing district and in the

World Trade Center also offer tax incentives that are not

available to tenants and building owners in East Midtown.

Cushman & Wakefield Projection.

The city planning department’s justification for the

East Midtown proposal relies in part on the office demand

estimates that Cushman & Wakefield produced for the 2012

Hudson Yards bond offering. At that time, Cushman &

Wakefield projected that demand for new office space in

Manhattan would total nearly 92 million square feet over the

next 30 years. Even after accounting for the 25 million

square feet of space that they predicted could be

accommodated in Hudson Yards, Cushman & Wakefield found that

there would be a 20 million square foot shortfall between

potential demand and what could be met by the market. City

planning argues that the 3.7 million square feet of new

office space in East Midtown would help to address some of

that potential shortfall.

Based on our analysis, it appears

that Cushman & Wakefield’s estimate may prove to be overly

optimistic. Cushman & Wakefield’s model is based primarily

on the historical relationship between employment growth and

the net absorption of office space, dating back to 1986.

By relying on a series of

regression models that assume a consistent relationship

between employment growth and net absorption, the firm

assumes that businesses’ demand for office space in the

future will respond to changes in economic conditions in

much the same way as in the past. In reality, the office

market has evolved over time—and continues to evolve—based

on the changing needs of tenants. Many of the companies that

absorbed the hundreds of millions of square feet built

across the region during the 1980s and 1990s now appear to

be cutting jobs or reassessing their space needs. Employment

among the financial and law firms that filled developments

like the World Financial Center in the 1980s and 1990s has

been flat since at least 2000, while vacancy rates in

suburban markets now approach or exceed 20 percent.10

The approach also does not

acknowledge the impacts of the ongoing diversification of

New York City’s economy. In the current recovery, growth

among office-using industries has been concentrated in

media, technology, advertising, and design, all of which

have different real estate needs than the companies in

finance, insurance, or legal services that drove earlier

expansions in the city. These businesses also occupy less

space per worker and employ fewer workers relative to large

firms with comparable levels of revenue in other sectors or

to large firms in prior decades.

The Cushman & Wakefield model uses

an employment forecast from Moody’s Analytics that is

aggressive based on historical trends. Its average annual

growth rate of 0.77 percent is higher than the peak-to-peak

average growth rate for office-using employment during any

single economic cycle dating back to 1969. Though Cushman &

Wakefield notes that this growth is comparable to growth

during the recovery from 2003 through 2008, it may overstate

average annual growth through multiple cycles of expansion

and contraction. While it is possible that the strong

employment growth during the current recovery will prove to

be sustainable, we consider it unlikely that the

office-using job market will outperform its historical

average for the next 30 years.

|

Demand Will Likely Match Supply In Baseline Growth Forecast

|

|

IBO Supply Forecast

|

Millions of Square Feet

|

|

Under Construction, Not Yet Leased

|

4.4

|

|

Potential Development Sites

|

36.6

|

|

Additional Capacity in Outer Boroughs

|

2.9

|

|

Subtotal, Capacity under Existing Zoning

|

43.8

|

|

Additional Capacity in Proposed

Midtown East

Rezoning

|

3.7

|

|

TOTAL, Existing and Proposed Capacity

|

47.5

|

|

IBO Demand Forecasts

|

|

|

Baseline Scenario: Growth of 0.5 percent a year,

200 square feet per worker

|

51.9

|

|

Other Scenarios

|

|

|

Growth of 0.75 percent a year,

250 square feet per worker

|

87.1

|

|

Growth of 0.75 percent a year,

175 square feet per worker

|

65.3

|

|

Growth of 0.5 percent a year,

250 square feet per worker

|

61.3

|

|

Growth of 0.5 percent a year,

175 square feet per worker

|

47.2

|

|

Growth of 0.25 percent a year,

250 square feet per worker

|

37.1

|

|

Growth of 0.25 percent a year,

175 square feet per worker

|

30.3

|

|

Cushman & Wakefield Demand Forecast

|

|

|

2011 Demand Forecast (Manhattan Only)

|

92.0

|

|

SOURCES: Cushman & Wakefield

NOTE: Totals may not add due to

rounding.

Independent Budget Office

|

Conclusion

IBO’s midrange estimate of demand

for office space, 51.9 million square feet through 2040, is

close to our estimate of citywide supply, which we expect to

rise to 47.5 million square feet after the proposed rezoning

of East Midtown. While our forecast is lower than that of

Cushman & Wakefield, it nonetheless suggests that there will

likely be enough demand over the next 30 years to support

the full build out of the World Trade Center, Hudson Yards,

and East Midtown, in addition to other sites in Manhattan,

Brooklyn, and Queens.

The wide range of potential

outcomes surrounding our midrange forecast, however,

highlights the considerable uncertainty involved in office

market forecasting over a 28 year time frame. Our model

illustrates how small changes in the rate of growth in

office-using employment and the space utilization rate can

significantly affect the demand for new office space.

Depending on how these rates change over time, demand for

office space in 2040 could be as little as 30 million square

feet or as much as 87 million square feet. Future shifts in

policy and structural change in the economy may also affect

the demand for space.

Even if the demand for office

space is at the low end of the range of estimates, the city

may still have legitimate reasons for wanting to rezone East

Midtown. If the neighborhood’s existing zoning constraints

discourage landlords from reinvesting in the Grand Central

area, then the rezoning could help satisfy a pent-up demand

for new office space in the area. The additional supply

could also make office rents more affordable citywide.

The District Improvement Fund plan

calls for the city to sell incremental development rights

and to spend the proceeds on pedestrian and subway

improvements in East Midtown. We have not taken a position

on the merits of these capital projects. The uncertainty in

our office market forecast, however, suggests that funding

capital projects with DIF revenue is not a risk-free

proposition. If DIF funds are used on a pay-as-you-go basis,

the plan would make high-priority capital projects dependent

on a volatile revenue stream that offers little certainty

about how much and on what schedule money will be available.

If the funds are used to reimburse upfront investments, the

city could be responsible for debt service payments on the

improvements for an unforeseeable period of time.

This report prepared by Sean

Campion

Endnotes

1

In both the 2004 report and

the current update, the terms "demand" and "supply" simply

refer to a quantity of space, regardless of price.

2

The "Midtown Development"

report is available on the city planning Web site here:

http://www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/pdf/history_project/midtown_development.pdf.

Other studies on the Special Midtown District proposal can

be found on the department’s History Project page:

http://www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/html/history_project/history_project_east_midtown.shtml

3Data

on employment is from Moody’s Analytics’ employment

database, which covers major industry sectors from 1970

through 2012. The sectors included in our definition of

office-using employment roughly correspond to the following

two-digit NAICS sectors: Information (51), Finance and

Insurance (52), Real Estate Rental and Leasing (53),

Professional, Scientific and Technical Services (54),

Management of Companies and Enterprises (55) and

Administrative and Support Services (56). Moody’s data

bridges between the current NAICS system and the previous

classification systems, dating back to 1970.

These

industries are surrogates for office-using employment. Not

all jobs in finance, information, or professional services

are located in offices. Conversely, the definition does not

capture the share of workers in other industries who work in

offices. For example, the corporate headquarters of a retail

company located in New York City contributes to the demand

for office space, even though it is classified in the retail

sector.

4

See:

http://www.costar.com/News/Article/Changing-Office-Trends-Hold-Major-Implications-for-Future-Office-Demand/146580

and

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/19/business/hotels-carve-out-work-spaces-rented-hourly.html?pagewanted=2&_r=0.

5

Estimates for New York

City’s natural office vacancy rate have varied in different

studies, though most studies have found that the natural

rate in cities with significant barriers to development,

like New York, Boston, or San Francisco, is around 7 percent

to 8 percent. See:

http://www.phil.frb.org/research-and-data/publications/business-review/1989/brmj89tc.pdf

or

http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2001/october/natural-vacancy-rates-in-commercial-real-estate-markets/.

6

The vacancy rate is for

Class A, B, and C office buildings in Manhattan’s Midtown,

Midtown South and Downtown office markets.

7

Cushman & Wakefield counted

2, 3, and 5 World Trade Center buildings as one development

site. It did not list 1 or 4 World Trade Center, since those

buildings were already under construction at the time of

that report.

8

See

http://www.nypost.com/p/news/business/groupm_signs_huge_year_lease_at_fOVuM7Z3GKlCuUUL1x9kVI

9

City planning has not

estimated the amount of net new office space that could be

built under on the revised zoning text amendment, which

allows developers to devote as much as 20 percent of the

floor area of office buildings to residential space or

hotels. The 3.7 million square foot estimate is based on

data from the original draft Environmental Impact Statement.

10

Partly in response to these trends, the current

owner of the World Financial Center recently rebranded the

development as Brookfield Place in order to attract tenants

besides financial firms.

PDF version available

here

Receive

notification of free reports by e-mail

Facebook

Twitter

RSS